- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: David Whish-Wilson reviews 'The Making of Martin Sparrow' by Peter Cochrane

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Just one thing can shape your whole life’ is one line in a novel of four hundred and fifty pages, but it is telling in its application toward the characters of this brilliant début novel. Set on the Hawkesbury River in 1806, the cast of characters is large and yet we find each of them living with the consequences ...

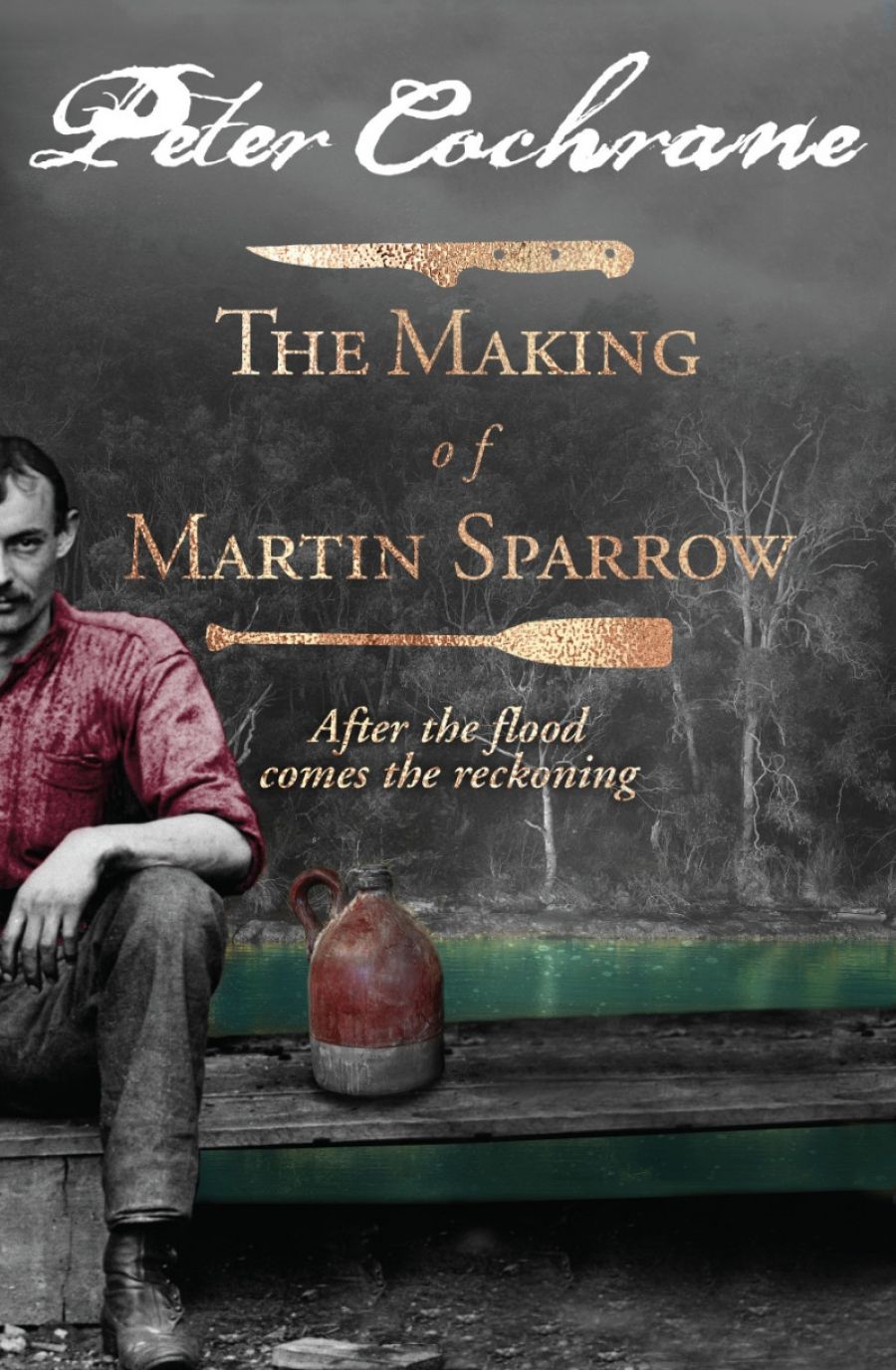

- Book 1 Title: The Making of Martin Sparrow

- Book 1 Subtitle: After the flood comes the reckoning

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $32.99 pb, 453 pp, 9780670074068

The harsh realities of life for the various settlers, soldiers, First Nations people, prostitutes, ticket-of-leave expirees, and administrators are brilliantly explored in the context of what one character, the estimable Thomas Woody, calls the ways and means of ‘the whole empire, like Rome, generous to the faithful servants of Caesar, pitiless toward enemies’. It is the yearning of one man in particular, the eponymous Martin Sparrow, which provides the narrative impetus that determines the fate of many of the novel’s characters, set against the recurring incidence of seasonal storms, flooding, and the quotidian tides. As an expiree suffering from jaundice and without the energy to work his land, Sparrow has a low opinion of himself: ‘He, Marty Sparrow, expiree, failed farmer, sad sack, yellowy man with no panache.’ Sparrow is a terrific fictional creation: he has a gentle heart plus a subtle aesthetic sensibility that usually finds expression when staring helplessly into space. In his misery and squalor, Sparrow is an easy mark for those spruiking dreams of the freedom to be had across the mountains. As put to him by game hunter and brute Griffin Pinney, the proposition is one of pure binary, where ‘there can be no middle state – it’s the misery of the mercantile tyranny or by God it’s the other side, the sovereignty o’ the commonweal, free of the brutish parties that govern us here’.

For all of the muck and brutality in The Making of Martin Sparrow, the cycles of atrocity and counter-atrocity, the novel strikes a perfect balance between the motivations and desires of the various characters vis-à-vis the institutional and historical forces that have brought them to this juncture. This is achieved largely through the subtle application of a roving point of view that allows the author to explore a great range of voice, and therefore social complexity, in a manner which feels authentic and never heavy-handed. On the topic of the new arrivals’ opinions and attitudes toward the area’s Aboriginal custodians, for example, the representation is varied and true to character. It is a real strength of this book that the novel’s Aboriginal characters – Old Wongan, Caleb, Napoleon, and others – acquire a strong sense of character.

There is wit and wisdom to be had in the book, too, particularly in the exchanges between Chief Constable Alistair Mackie and his subordinate Thaddeus Cuff. The former is a pragmatic Scotsman who has quietly amassed wealth and influence, and for whom ‘My good fortune began when I stepped off that transport.’ Cuff, on the other hand, is a capable American with a rover’s happy-go-lucky attitude and a matter-of-factness that sees potential in the new land, beyond the ledgers and accounts that occupy the rule-bound but generally humane Mackie’s thoughts.

Peter Cohrane (photo by Jason McCormack)In the context of Peter Cochrane’s career as an esteemed historian, and some of the discourse over the past decades relating to the capacities of fiction and history to capture the complexity of the past, it is both Mackie and Cuff who speak on the subject during some of their many entertaining passages of dialogue. Mackie goes first when he says that ‘History’s naught but gossip well told’, whereas Cuff chimes in later with the pointed observation that ‘history and the drizzles is close cousins … There’s a great deal of fluid prejudice in both of them.’ It is Cuff, however, as a man whose experiences have taught him to believe that humans are little better than snakes, who speaks most forcefully to the present, and the writing of history along national myths, when he sadly observes that ‘It’s the first settlers do the brutal work. Them that come later, they get to sport about in polished boots and frockcoats, kidskin gloves … revel in polite conversation, deplore the folly of ill-manners, forget the past, invent some bullshit fable … You want to see men at their worst, you follow the frontier.’

Peter Cohrane (photo by Jason McCormack)In the context of Peter Cochrane’s career as an esteemed historian, and some of the discourse over the past decades relating to the capacities of fiction and history to capture the complexity of the past, it is both Mackie and Cuff who speak on the subject during some of their many entertaining passages of dialogue. Mackie goes first when he says that ‘History’s naught but gossip well told’, whereas Cuff chimes in later with the pointed observation that ‘history and the drizzles is close cousins … There’s a great deal of fluid prejudice in both of them.’ It is Cuff, however, as a man whose experiences have taught him to believe that humans are little better than snakes, who speaks most forcefully to the present, and the writing of history along national myths, when he sadly observes that ‘It’s the first settlers do the brutal work. Them that come later, they get to sport about in polished boots and frockcoats, kidskin gloves … revel in polite conversation, deplore the folly of ill-manners, forget the past, invent some bullshit fable … You want to see men at their worst, you follow the frontier.’

Following the frontier, and beyond, is precisely the direction the novel takes as each of the main characters set out from their respective homes along the river into the hinterland, triggering a chain of events both terrible in consequence but also potentially redemptive. It is here, too, that Cochrane employs some of his finest writing, embarking upon perfectly modulated descriptive riffs that betray an appropriate sense of awe and developing understanding for what is a vast, ancient, storied landscape – a terrific accompaniment to the pitch-perfect dialogue and deep characterisation found in this fine novel. ‘They heard the sound of frogmouths and boobooks and night-birds unknown to them, and they heard the whoosh and smack of fish jumping in the shallows and the constant sound of the tide chafing the banks and far off howling, and they saw river-rats scurrying for cover and myriad shapes in the dark recesses of the forest and higher up they saw great bands of ancient sandstone, moonlit, cracked and fissured by the chisel work of ages.’

Comments powered by CComment