- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

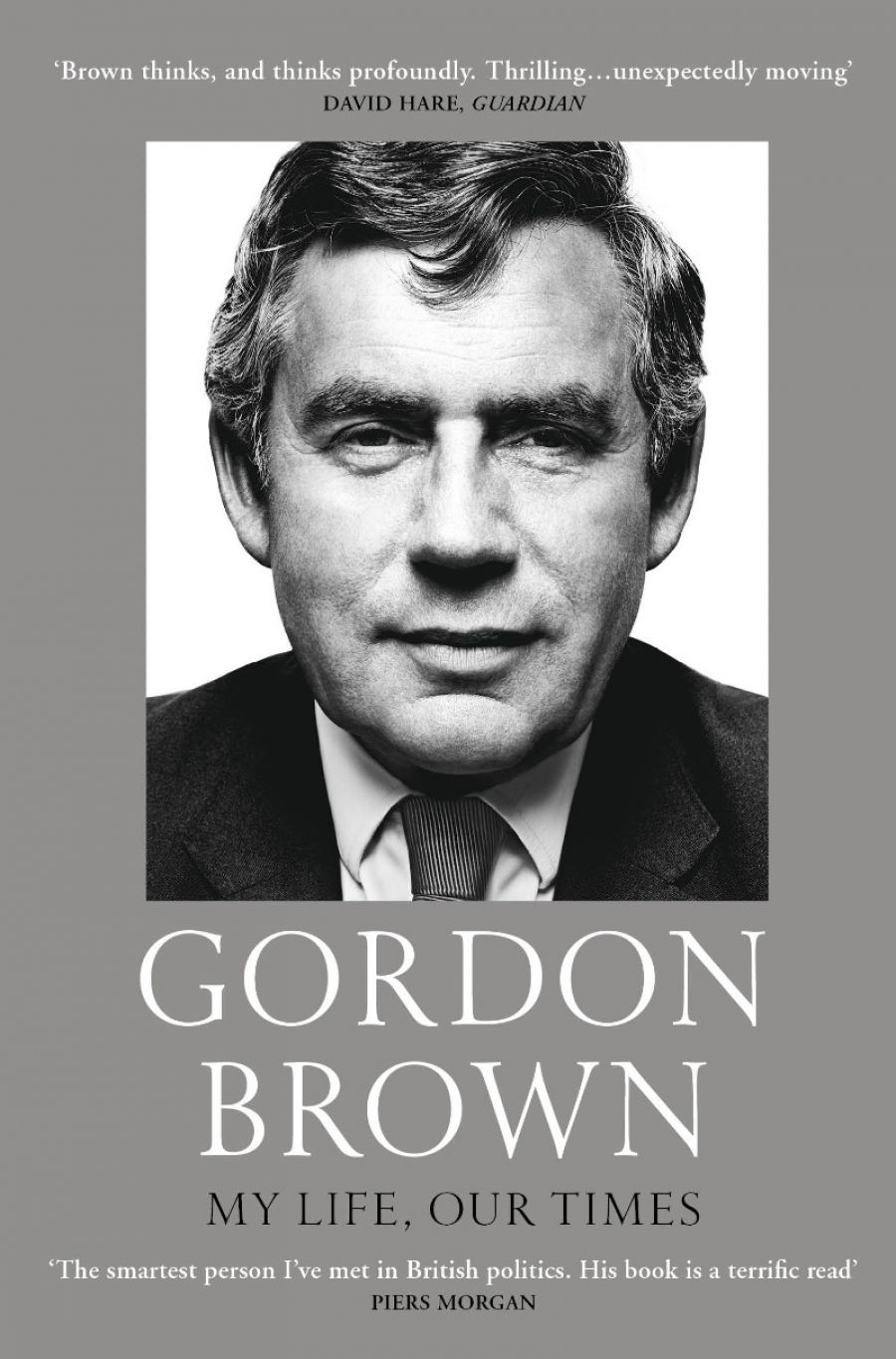

- Custom Article Title: Simon Tormey reviews 'My Life, Our Times' by Gordon Brown

- Custom Highlight Text: It is a cliché to note that Gordon Brown is an enigma as far as contemporary British politics is concerned. A fundamentally decent man of high moral standing, Brown forged with Tony Blair arguably the most successful political partnership the United Kingdom has known ...

- Book 1 Title: My Life, Our Times

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $22.99 pb, 512 pp, 9781784707460

Everyone looks first at the nature of the relationship between Blair and Brown. That it was tetchy and marked by suspicion of each other’s motives, personality clashes as well as substantive differences over the direction of policy, is already well documented. Less evident, until now, is the degree of divergence on strategy. Brown’s instincts were to build credibility with the right-wing media, international finance, and key élites. This meant keeping a tight rein on spending to ensure that the public finances were primed for investment. Blair, clearly a more intuitive politician, craved the big headline, the new initiative that would show him in the best possible light. A large part of the narrative here is given over to deconstructing the impression that the struggle between the two related to issues concerning what they wished to do, when often it was a matter of how and when they would do it – whether it be finding extra funding for the National Health Service or increasing support for those in need. As becomes clear, Blair’s instincts were political and based on expediency. Brown’s were technocratic and based on considerations of utility. While this combination served them well for a decade, it was also combustible, making for frequent headlines concerning the poisonous relationship between numbers Ten and Eleven Downing Street. History records the trials and tribulations but not, unfortunately, the triumphs.

Secondly, Brown was to fall victim to one of the laws of modern politics: electorates have low boredom thresholds. Again, this is an item touched on throughout the book. Knowing that Labour would have two and at best three terms in office, Brown thought he had agreed to a deal with Blair to take over mid-term in the second government (2001–5). Clearly, Blair thought otherwise, consigning Brown to the butt end of the third term (2005–10), when the electorate began to tire of Labour. In addition, Blair’s folly at following Bush into Iraq meant the third term would always be overshadowed by accusations of imperialism and misadventure. Add in the effects of the global financial crisis in 2008, the implosion of UK banks, and a contagion that consumed much of the available public cash, and it is clear that no matter what Brown was intending, events made his tenure as demanding as it is possible to imagine. Even so, his account makes apparent that he showed remarkable leadership, internationally as well as domestically. Seeing the liquidity issue sooner than many of his counterparts, Brown argued forcibly for the immediate injection of credit into the system, which in turn prevented it from collapsing entirely. Brown’s name might be tarnished as far as the broader electorate is concerned, but clearly his élite peers have a great deal to thank him for.

Gordon Brown, official portrait while Leader of the Labour Party in 2009 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)Brown does a fine job defending himself and his legacy against the charge of dullness on the one hand and ineffectuality on the other. Yet the book does little to help us locate the elephant in the room: the collapse of social democracy and the kind of élite-driven, ameliorative politics that Blair and Brown stood for. Ultimately, if we want to understand why the stock of social democratic figures such as Brown is so low, we need to go further.

Gordon Brown, official portrait while Leader of the Labour Party in 2009 (photo via Wikimedia Commons)Brown does a fine job defending himself and his legacy against the charge of dullness on the one hand and ineffectuality on the other. Yet the book does little to help us locate the elephant in the room: the collapse of social democracy and the kind of élite-driven, ameliorative politics that Blair and Brown stood for. Ultimately, if we want to understand why the stock of social democratic figures such as Brown is so low, we need to go further.

The nub of the issue is surely the Faustian nature of the bargain between a species of social democracy and the market and ‘globalisation’. Social democracy was built on the credo that capitalism would not collapse of its own accord, and thus that progressive politicians had to embrace the market and develop growth-friendly policies that would in turn underpin generous welfare provision ‘from cradle to grave’. That worked under conditions of limited capital flows and strong national economies. It still does as the examples of various European economies, not least Germany, shows.

Under the aegis of Nigel Lawson and then Brown, the United Kingdom took a different path. It outsourced its manufacturing base, redesigning itself as a haven for unlimited capital flows, deregulated derivatives, over-leveraged banks, and financialised capitalism (the current phase of capitalism that seeks to generate profit based on financial innovation rather than innovation in production). This was all heralded by Brown as a new ‘golden age’ for the City of London, a mere matter of months before the bubble burst. Given London’s dominance in terms of exports and earnings, the United Kingdom was hit particularly hard. The public finances were trashed with bailouts worth billions given to failing banks. This led to the double whammy of a serious recession coupled with the imposition of austerity policies by David Cameron’s government off the back of Labour’s humiliating defeat in the 2010 election. From here it is but a short step to the rise of anti-EU, anti-foreigners nativism, and, ultimately, the ‘leave’ result in the Brexit referendum of 2016.

Tony Blair, taken during Gordon Brown's Prime Minstership in 2009 (photo via the Center for American Progress/Flickr)

Tony Blair, taken during Gordon Brown's Prime Minstership in 2009 (photo via the Center for American Progress/Flickr)

It would no doubt be harsh to lay all the mess at the feet of Brown, but given the valedictory nature of the book, it would also be remiss not to query a narrative that sees Brown as more sinned against than sinning. The point is that had Brown shared the same scepticism towards the direction of travel of financialised capitalism as did many of his peers on the European mainland, had he invested more in industrial policy and in encouraging native manufacturing, as opposed to lauding the miracle of derivatives and speculative investment, the outcome might have been different – for him and for social democracy in the United Kingdom. Brown seems a reasonable, indeed likeable character on the basis of this book. But he is also a proud one, too proud perhaps to recognise that his own ideology – ‘third way’ financialised social democracy – was complicit in the chaos and uncertainty that has led to the collapse in confidence in technocratic politicians and the resort to protectionism and nativism as answers to globalisation.

Comments powered by CComment