- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

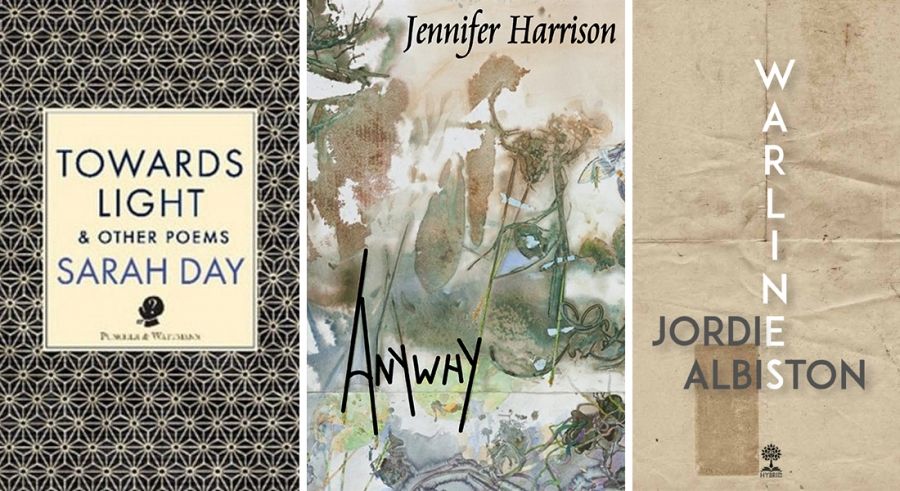

- Custom Article Title: David McCooey reviews three poets at the height of their powers

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sarah Day’s début collection, A Hunger to Be Less Serious (1987), married lightness of touch with depth of insight. In Towards Light & Other Poems (Puncher & Wattmann, $25 pb, 108 pp, 9781925780024), Day continues this project in poems concerned with light, a thing presented as both ...

As this image suggests, a key feature of Day’s poetry is its interest in mutability. The world is a source of both joy and anxiety because things are so changeable. Even things that appear fixed can be disconcertingly fluid. The sonnet ‘Fe’, which takes its title from the periodic table’s symbol for iron, notes that ‘Magnetic north is always on the move’, ‘gliding now at forty k per year from Canada / towards Siberia like a planchette on a Ouija’. Miraculously, the poem explains, such changeability does not confuse migrating animals.

Non-human animals occupy an important place in Day’s light-filled world. It is perhaps evidence of Day’s great openness to the otherness of animals that the poem that most moved me was about the death of a chicken. Such attention to the natural world also extends to plant life. ‘First There, First Serve’, a description of time-lapse footage, shows how dramatic – in a literal life-and-death sense – the world of plants can be.

This collection, so concerned with mobility, change, and struggle, comes to a profoundly moving end with the sequence of poems ‘The Grammar of Undoing’ on the poet’s mother and her experience with Parkinson’s disease. In these poems, the dialectic between light and dark – praise and elegy – is rendered with tremendous power and sensitivity. They show Day to be a quietly original poet, worthy of readers’ deepest consideration.

Anywhy by Jennifer HarrisonLike Day’s latest book, Jennifer Harrison’s new collection, Anywhy (Black Pepper, $24 pb, 78 pp, 9781876044190), is concerned with the dynamic between light and dark, self and other. Like Day, Harrison has a deep concern for non-human animals. ‘The Animals’, about the burning of the Warsaw Zoo during World War II, is a particularly harrowing example of this concern. Also like Day, Harrison illustrates a post-Romantic interest in the natural world, but here there is a more explicit acknowledgment of the Anthropocene that we have brought into being.

Anywhy by Jennifer HarrisonLike Day’s latest book, Jennifer Harrison’s new collection, Anywhy (Black Pepper, $24 pb, 78 pp, 9781876044190), is concerned with the dynamic between light and dark, self and other. Like Day, Harrison has a deep concern for non-human animals. ‘The Animals’, about the burning of the Warsaw Zoo during World War II, is a particularly harrowing example of this concern. Also like Day, Harrison illustrates a post-Romantic interest in the natural world, but here there is a more explicit acknowledgment of the Anthropocene that we have brought into being.

Harrison, who is also a psychologist, habitually incorporates putatively non-poetic registers – especially scientific discourse – in her poetry. She is notably wide-ranging in her interests. Poems in Anywhy cover ancient history and archeology, war, photography, suburbia, birdlife, and so on. A number of poems are ekphrastic in nature, which is to say they respond to other works of art, such as a famous photograph by Walker Evans.

This is not to say that Harrison’s poetry is merely random in its concerns. It has a number of unifying features. The neologistic title of Anywhy illustrates Harrison’s love of linguistic play. There are, for instance, two ‘Air Variations’ that employ words with particular initial letters (C and D, and L and M, respectively) to produce a rich musicality, even as they cast a characteristically cool eye over the world. In ‘DNA’, various versions of that famous abbreviation illustrate Harrison’s serio-comic inventiveness: ‘Developmental Needs Analysis / Digital Network Architecture / Do Not Abbreviate’.

As these poems illustrate, Harrison can allow the comic and the elegiac to occupy the same poetic space. In the apparently self-elegiac poem ‘The Exchange, Blackwood Village’, the poet meditates on life after cancer: ‘Death found my measure in its pill of greed / and I carry the taste inside like a baby, never to birth.’

Ultimately, with its emphasis on different types of media and discourses, Harrison seems to be concerned with representation itself, and with representation as something that takes in both sympathy and violence. When she quotes the Hungarian war photographer Robert Capa – ‘if the photograph is not good enough / you aren’t close enough’ – one gets the sense that she is offering a description of her own poetics. Harrison is a poet of close-up photography, anatomy, and intensity, and this latest collection shows her to be at the height of her powers.

Warlines by Jordie AlbistonJordie Albiston’s Warlines (Hybrid, $25 pb, 160 pp, 9781925736090) is, as its author notes, a collection of found poems. Using the letters and postcards of Australian soldiers from World War I, Albiston has produced a work that brings together prose poetry, documentary, history, and curatorial art. Each poem uses the correspondence (often producing a mosaic from multiple letters or postcards) of an individual soldier. The soldiers have names like Rupert Stanley Lawford and Phillip Murray Portsmouth Knight. They are names from a different (and considerably more monocultural) age, and the merging of proper name and poem is integral to the effect of this extraordinary work.

Warlines by Jordie AlbistonJordie Albiston’s Warlines (Hybrid, $25 pb, 160 pp, 9781925736090) is, as its author notes, a collection of found poems. Using the letters and postcards of Australian soldiers from World War I, Albiston has produced a work that brings together prose poetry, documentary, history, and curatorial art. Each poem uses the correspondence (often producing a mosaic from multiple letters or postcards) of an individual soldier. The soldiers have names like Rupert Stanley Lawford and Phillip Murray Portsmouth Knight. They are names from a different (and considerably more monocultural) age, and the merging of proper name and poem is integral to the effect of this extraordinary work.

Each poem ends with a note containing the essential biographical details of these men: their age, the year they enlisted, where they were deployed, and so on. Each piece ends with an abbreviation, most commonly ‘DOW’ (died of wounds), ‘KIA’ (killed in action), and ‘RTA’ (returned to Australia). After being so present in Albiston’s rendering of their words, then, we discover the fate, if one can use such a word, of each soldier. It is impossible to describe the intensity of this as a reading experience. Each discovery is profoundly moving. If this book is almost ‘too much’, it does its job in helping us imagine the inconceivable ‘too much’ that was the mass slaughter of World War I.

Albiston reworks her source material into highly formal and stylised linguistic works. Warlines is – like her other collections – a technical tour de force. As the book’s blurb tells us, the poems contain hidden forms such as the sestina and the villanelle. These are, I would guess, completely hidden for most readers, but more basic elements of stylisation – repetition, rhyme, acrostic and palindromic organisation – are more apparent. And even if those elements aren’t recognisable, the profound exchange between Albiston and the source texts she transforms is eminently clear. Albiston has produced a work that is by turns strange, funny, dramatic, and deeply sad.

The tonic note of this collection, inevitably, is that of pathos – the pathos of needless loss and unspeakable suffering. To choose just one instance, there is George Cummings’s account of being with the parents of a recently killed friend: ‘they took their lot bravely & I wanted to [?] so they would not feel their loss so keenly they treated me like their own boy’. The question mark denotes an illegible word, but it is also aesthetically appropriate, given the unspeakability of the event.

As this suggests, each man/poem has his/its own individuality. Whether the epistolary language used is religious, sentimental, romantic, comic, or documentary, no one man or poem is like the other. Albiston allows each soldier’s individuality to manifest itself. In using their words to produce works of art, she gives them a dignity that few writers (and almost no politicians) offer them. She shows their words to have real worth, both in themselves and as part of the greater project of humanity we call creativity. Most importantly, Albiston transforms these men’s words into art, while resolutely avoiding myth and mystification.

One rarely wants to evoke the term ‘masterpiece’. It seems either debased or too reliant on subjectivity. I don’t deny its subjective nature, but I can’t think of a better term to describe this book. In our war-obsessed culture, one in which the ‘Anzac legend’ is used for increasingly dubious ends, Warlines should be required reading. Albiston wrote Warlines with the assistance of a State Library Victoria Fellowship. I can think of few better arguments for public assistance of the arts.

Comments powered by CComment