- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Antarctica

- Custom Article Title: Awesome Mawson

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Awesome Mawson

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Antarctic exploration began with Captain James Cook’s circumnavigation of the continent (1772–75) and continued intermittently until the first two decades of the twentieth century. Douglas Mawson’s three expeditions coincided with what has been called the ‘heroic era of Antarctic exploration’, beginning with Robert Falcon Scott’s British National Antarctic Expedition (1901–4) and ending with Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914–17). Four out of the twenty expeditions undertaken in this period stand out: those of Roald Amundsen, Mawson, Shackleton and Scott. However, the present-day polar adventurer Ranulph Fiennes has argued that Mawson did not achieve the fame of the other three, even in Australia, because he survived his explorations and died in old age.

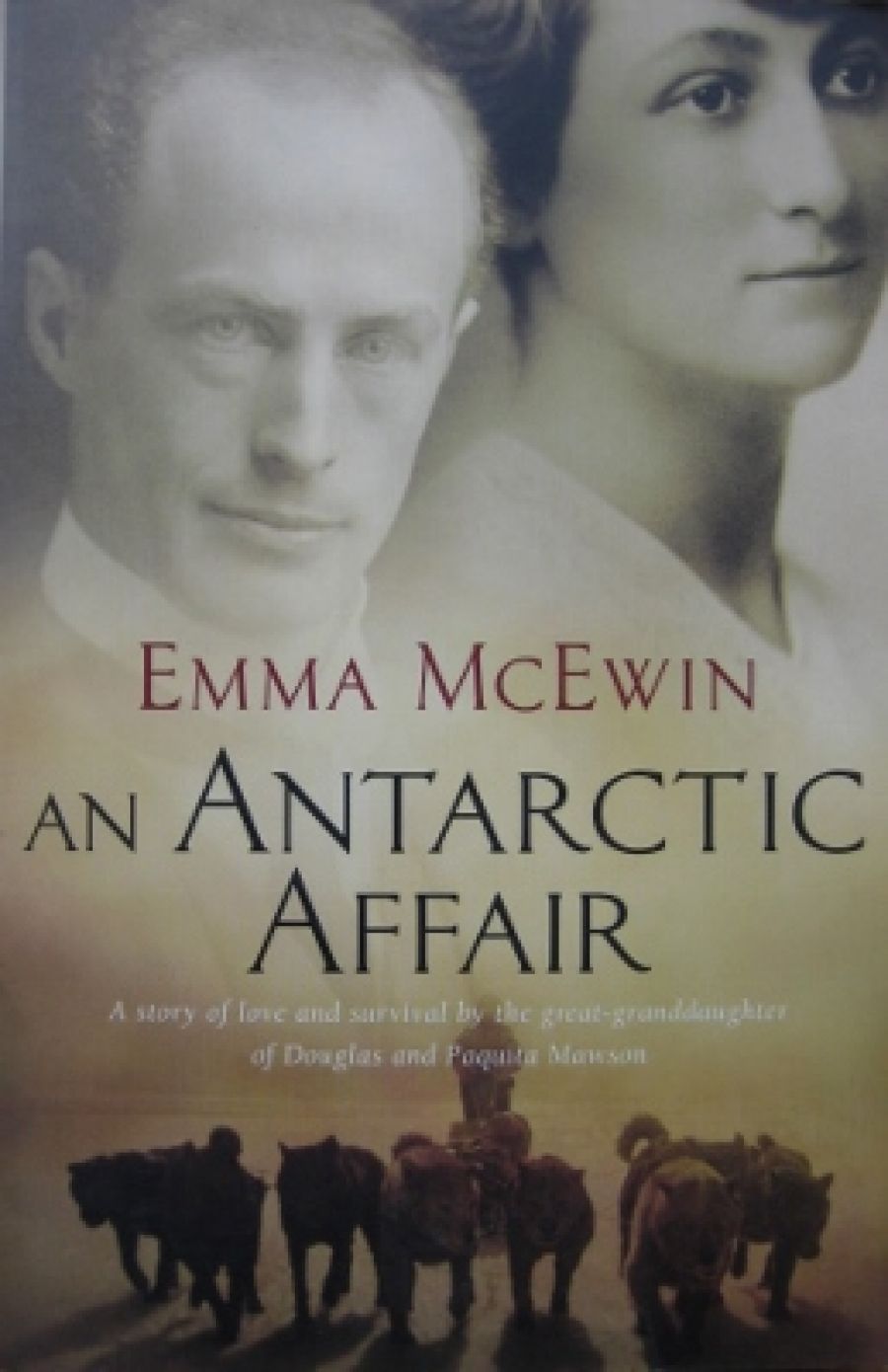

- Book 1 Title: An Antarctic Affair

- Book 1 Subtitle: A story of love and survival by the great-granddaughter of Douglas and Paquita Mawson

- Book 1 Biblio: East Street Publications, $32.95 pb, 254 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Unlike Scott and Shackleton, who were in Antarctica at the same time, Mawson had no intention of reaching the South Pole. He did not wish for national or individual glory; science, adventure and the wish to travel over virgin territory were his driving forces. With two companions, British surveyor Lieutenant Belgrave Ninnis and Dr Xavier Mertz, a Swiss lawyer and engineer who was also an alpine guide, he set out to travel further along the east coast than anyone had yet been, recording geographical, geological and meteorological details as he went. They faced appalling conditions: gale-force winds, seemingly endless snow hills and crevasses, recalcitrant sledge dogs, inadequate food. The three never reached their destination. When Ninnis fell down a crevasse, Mawson and Mertz turned back. Mertz then died horribly with what was subsequently diagnosed as Vitamin A poisoning. Mawson continued alone, reaching base camp in time to see the rescue vessel steaming away.

This month-long solo trek marks Mawson’s story as extraordinary and distinct. How did he manage it when rations were almost exhausted, and even all the dogs had been eaten? Rumours were rife. Did he eat Mertz? McEwin bravely tackles the question, presenting arguments for and against cannibalism. She reasons that Mawson could, and indeed would, have eaten human flesh, but he did not need to. Her calculations are unclear, but she contends that his ‘personal’, uncounted rations would have been sufficient to sustain him on his perilous journey, even in his weakened condition. She also believes that Paquita’s love and the promise of life with her played a vital role in his survival.

McEwin draws this conclusion from the love letters, which she finds ‘crucial to an understanding of the whole story’. These were tender but, on Paquita’s part, increasingly ‘full of anguish’ as she began to doubt Mawson’s love and commitment. She did not hear from him for twenty-two months: there was no mail service to the Antarctic. He was more fortunate, receiving mail from her when a ship arrived after fourteen months. Yet this was after his return to base camp. When he was alone in the vast wilderness, he had no idea that she waited so anxiously for him.

While the letters reveal the emotions of the lovers, there are too few to sustain this as ‘a story of love’, as proclaimed on the cover. Paquita wrote only nine letters over the whole period, Mawson just two from Antarctica before he set out on his expedition, more frequently in his second winter, but still not a great number. Family memories of McEwin’s great-grandfather add to the personal touch, but she is too close to her subject. She refers to Mawson as ‘Douglas’ and to her great-grandmother as ‘Oma’; all others, except, strangely, Professor David and Dr Mackay, she refers to by only their family names. Her awe of Mawson inclines her work to hagiography. She dismisses criticism about his character and frequently lists his virtues: ‘a strong work ethic, a highly organised mind, self-confidence, self-motivation, self-sufficiency and self-discipline’ – and this is just one of many instances.

The author is no stylist. She tells a thorough story, but the reader never gets a sense of the perils of the frozen wastes or of their pristine wonders. Whether because of poor editing, or simply ignorance, the work is marred by mistakes: ‘sewed the seeds’, ‘landing at his chosen sight’ and ‘Australian Bite’ (Great Australian Bight) should have been corrected.

The strength of the work is its overview of polar exploration and Mawson’s place in this. If you do not know why and how Australia acquired so much territory in the Antarctic, this is a good place to start.

Comments powered by CComment