- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Patrick McCaughey reviews 'Modernists and Mavericks: Bacon, Freud, Hockney and the London Painters' by Martin Gayford

- Custom Highlight Text:

The geography of art post 1945 has a boringly settled look and needs disturbing. This engaging and readable book makes a useful starting point. The standard view begins with the switch of the centre from Paris to New York, and so it remained for the next fifty years or so until ...

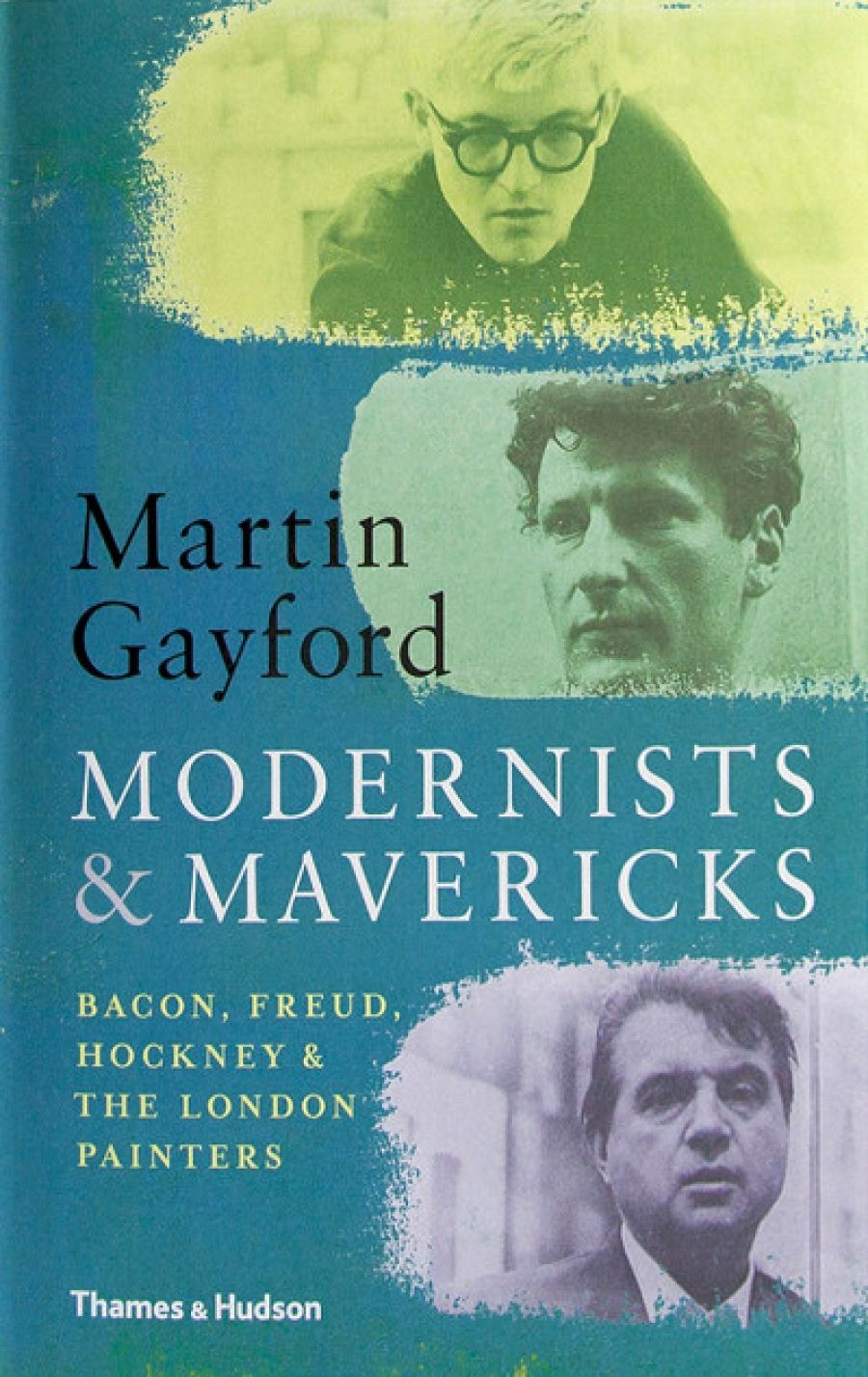

- Book 1 Title: Modernists and Mavericks

- Book 1 Subtitle: Bacon, Freud, Hockney and the London Painters

- Book 1 Biblio: Thames & Hudson, $50 hb, 340 pp, 9780500239773

Europe had individual masters such as Francis Bacon, Antoni Tàpies, Anselm Kiefer, and Alberto Burri. Sculpture had Alberto Giacometti, Anthony Caro, and Henry Bore (aka Moore), a darling of American corporate taste. There were even transient movements in European art, which attracted international attention, notably the Italian Transavanguardia – Enzo Cucchi, Francesco Clemente, and Mimmo Paladino – and the German neo-expressionists A.R. Penck, Georg Baselitz, and Sigmar Polke. But New York stubbornly retained its centrality, buoyed by the dominance and excess of its contemporary art market. Late into the 1980s, Frank Stella could still claim, unwisely, unblushingly, that major art could not be made outside of New York.

But how dominant was New York in the period from 1945 to 1995? It’s an open question. The pattern of Western art was not synonymous with the course of American art as Martin Gayford’s informal history of the School of London tactfully implies. Gayford avidly records artists’ thoughts and opinions. His Eckermann-like account of Lucian Freud in The Man in the Blue Scarf documents the experience of having your portrait painted by the Rembrandt of Kensington Church Street. The present book Gayford calls ‘a collective interview or multiple biography … recorded over three decades’, ranging from Frank Auerbach and Gillian Ayres to John Virtue and John Wonnacott. The method has assets and imitations: there is a sympathetic intimacy with artists, but it cauterises critical judgement.

It elicits, however, such startling remarks as Gillian Ayres’s statement that really links the disparate School of London. The abiding issue for Ayres was: ‘What can be done with painting?’. It was both question and assertion. It made for a self-questioning, self-doubting mode and privileged highly individual styles and idiosyncratic subjects. The School of London embraced such antithetical sensibilities as the diffidence of Michael Andrews and the brute force of Francis Bacon. Could you have two more different virtuosos of the brush than Lucian Freud and David Hockney? Hence comes the characterisation ‘maverick’. Frank Auerbach, as central to the school as anyone, sees Hockney, Bacon, and Freud coming from a line of British maverick artists, ‘people who did exactly what they wanted to do, such as Hogarth, Blake, Spencer, Bomberg’.

Such a situation gave women artists a better chance than elsewhere. Of course, they had to struggle, but Ayres, the first woman to head a painting department in the United Kingdom, at the Winchester School, was an inspirational teacher. Prunella Clough was given a retrospective at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1960 and another in 1975 at the Serpentine Gallery. Sandra Blow was taken up early in her career by Gimpel Fils, a leading international art dealer. Most prominently, Bridget Riley lived down and painted through her early, sensational op art style to become a major force in British art. Paula Rego was their heir. Collectively, they broke into the ‘boys only’ atmosphere of the School of London.

Francis Bacon, 1962 (photo by Irving Penn via cea +/Flickr)

Francis Bacon, 1962 (photo by Irving Penn via cea +/Flickr)

The Brits enjoyed an anomalous relationship with New York. Most contemporary British artists were aware of American-type painting from the early 1950s – some, like Alan Davie, even earlier. Fred Williams remembered seeing Blue Poles at the Institute of Contemporary Art in 1952, and the Jackson Pollock retrospective at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1958 had a galvanic effect. Gayford notes that David Hockney hitchhiked down from Bradford to see it. Bacon was studiously unimpressed. Pollock reminded him of ‘a collection of old lace’, and he went on to make the outrageous claim that Elinor Bellingham-Smith, a still-life and landscape painter, and wife of the artist Rodrigo Moynihan, was a better artist. Auerbach, always the more generous and perceptive, was unambiguous: ‘What the Americans did was to re-assert the standards of grandeur.’

Pollock offered a freedom to British artists away from the edicts of the life-drawing classroom. How you moved the paint around was what mattered. Auerbach and Leon Kossoff, both rooted in the grimier aspects of the London scene, found release in Pollock’s energetic abstraction. Both had sought out David Bomberg as a mentor in the unfashionable Borough Polytechnic on the wrong side of the river and had taken to heart his mantra seeking ‘the spirit in the mass’. Harold Rosenberg’s phrase that the canvas had become ‘an arena in which to act’ struck a nerve in Ayres. She produced the most advanced abstract painting in Britain in the 1950s under its aegis.

Lucian Freud (photo via Claudia Gabriela Marques Vieira, Bruce Bernard, Artist Muse, Study Gallery/Flickr)

Lucian Freud (photo via Claudia Gabriela Marques Vieira, Bruce Bernard, Artist Muse, Study Gallery/Flickr)

Martin Gayford develops the theme of British delight in all things American from popular culture and cinema to skyscrapers and cereal packaging in the late 1950s. They would be the fuse and detonator of British Pop Art. Unquestionably, British Pop Art preceded the American version. In the hands of Richard Hamilton, Richard Smith, and Peter Blake, it had a richer, more painterly quality than their transatlantic coevals. British Pop Art petered out in the 1970s. Only Patrick Caulfield had a sustained career in a pop mode to match Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, or James Rosenquist. But it nurtured the genius of David Hockney, whose liberating passion for America, from Los Angeles swimming pools and their denizens to the Grand Canyon, gave the middle period of his art its brilliance and complexity.

The geography of contemporary art remains a puzzle. If you asked the cognoscenti in London for the names of the most important figures in recent art, you would get: Bacon, Freud, and Hockney, possibly Howard Hodgkin, one hopes Riley, Auerbach, and Kossoff, maybe Ayres for the well informed. None of these would be on a New Yorker’s top ten: Richard Serra, Ellsworth Kelly, Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, Agnes Martin, and the minimalists would all precede them. At the time of writing, only one of the seven Bacons in MoMA’s collection is on view. The Modern has no painting by Lucian Freud later than 1949.

If, however, we were to interleave the School of London and other major European figures with American art and artists, it would profoundly enhance the story of late modernism. It would possess a richer texture, more humanist in outlook, less conceptual, resonating the anxieties and aspirations of the age.

Comments powered by CComment