- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Custom Article Title: Brian Matthews reviews 'Antipodean Perspective: Selected Writings of Bernard Smith' edited by Rex Butler and Sheridan Palmer

- Custom Highlight Text:

The editors begin their introduction to Antipodean Perspective with some ground clearing: ‘The putting together of a series of responses to an important scholar’s work is a classic academic exercise. It is undoubtedly a worthy, but also necessarily a selective undertaking. In German it is called a Festschrift …

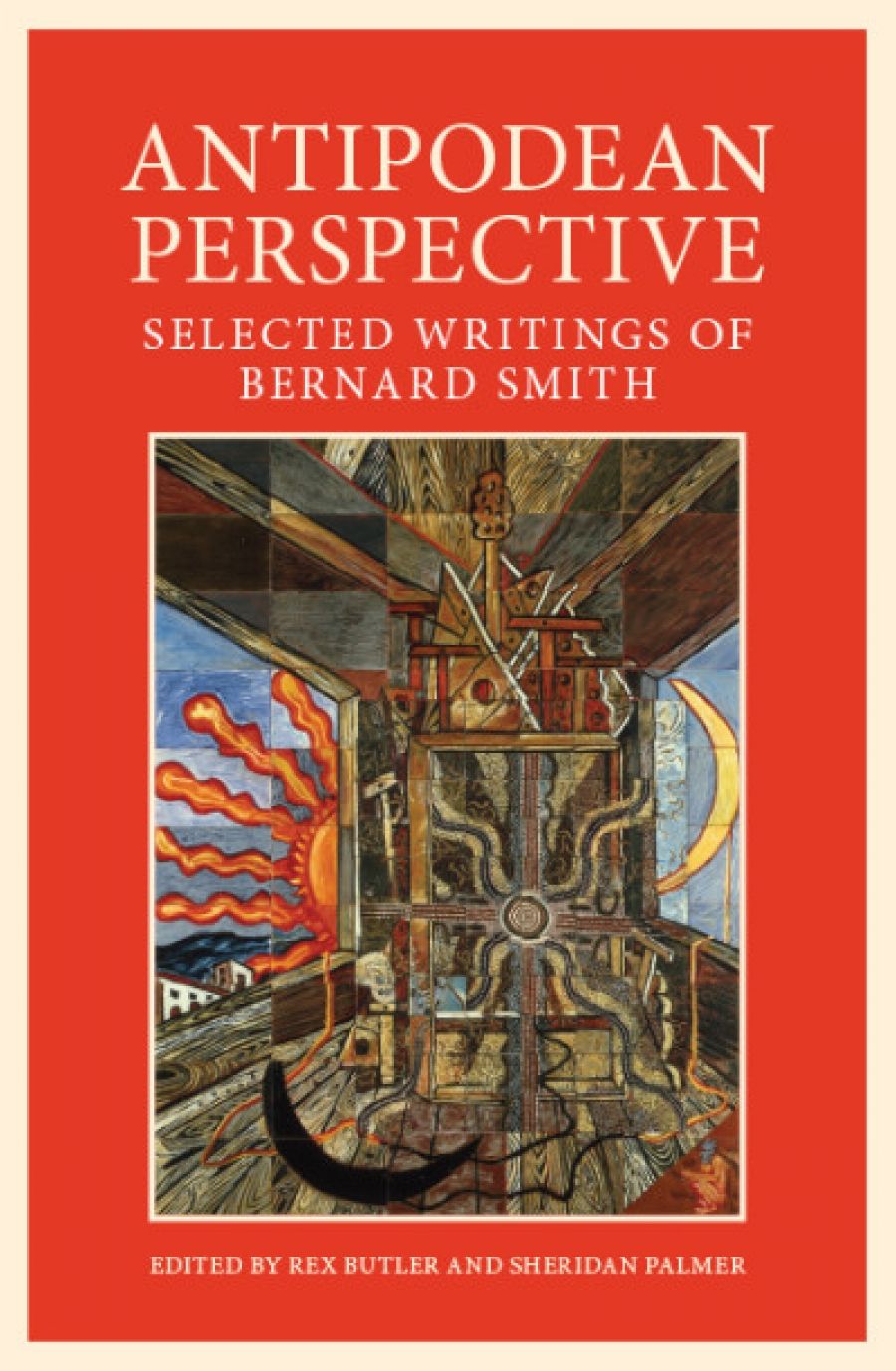

- Book 1 Title: Antipodean Perspective

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected Writings of Bernard Smith

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $29.95 pb, 425 pp, 9781925495669

Antipodean Perspective belongs in this general category, but it is interestingly and fruitfully different. In what might be called the standard Festschrift, the honouree is of course referred to in detail: it’s rather like an academically slanted ‘This is your life’. Antipodean Perspective, however, assigns the commentary and reminiscence to carefully chosen interlocutors, both venerable and youthful, who, by and large, make relatively brief but, at least in this case, penetrating or enlarging contributions on specific texts which they choose, while the honouree, Bernard Smith (1916– 2011), is represented by substantial quotation from those texts or, in some cases, their complete reproduction.

This departure from more or less standard Festschrift practice is part of the reason why this collection is so beautifully and continuously evocative of the man himself. There are many voices here, but Smith’s is, properly and characteristically, the strongest without, in general, being strident, insistent without being cajoling.

This is a big book, but it is probably best read from the beginning – Tim Bonyhady’s Chapter 1 commentary on ‘Impressionism in Australia’ (Place, Taste and Tradition, 1945) – to the end: Emma Hicks’s Chapter 25, ‘A Distant Relationship’. This way, the voices of the contributors proliferate, becoming not a cacophony but a kind of aural tessellation of emerging patterns, colours, harmonies, and dissonance Smith’s own voice sounds with varying notes of assurance, emphasis, speculation, theorising, producing that effect to which the editors refer in their introduction: as ‘Each contributor [selected] a text or excerpt from Smith’s writing that meant something to them personally and that they would like others to read and [for which each writes] a brief introduction … in an uncanny way, there was the sense that Smith himself had already written in advance how they could respond to the work.’

Inevitably, some selections and commentaries stand out. It will come as no surprise that one of these is ‘The Antipodean Manifesto’ (1959). Bernard Smith’s truculent opening remarks left no room for misunderstanding the provenance and central concerns of the ‘manifesto’:

Let it be said in the first place that we have all played a part in the movement which has sought for a better understanding of the work of contemporary artists both here and abroad … But today we believe like many others, that the existence of painting as an independent art is in danger. Today tachistes, action painters, geometric abstractionists, abstract expressionists and their innumerable band of camp followers threaten to benumb the intellect and wit of art with their bland and pretentious mysteries. The art which they champion is not an art sufficient for our time, it is not an art for living men. It reveals, it seems to us, a death of the mind and spirit.

And yet wherever we look – New York, Paris, London, San Francisco, Sydney – we see young artists dazzled by the luxurious pageantry and colour of non-figuration …

Although this is not the only place in the collection where it happens, the editorial strategy of inviting commentators to offer a prefatory statement about their chosen Smith moment is seen at its best here. Ronald Millar is witty and pointed, but not needlessly acerbic: ‘Painters make their own myths, which may have less to do with their physical surroundings than their inner life and the potential connections of that life to the lives of others. The means of communicating this may very well be non-figurative, and not necessarily a “withdrawal from life.” … At this distance from the event,’ he suggests, ‘[the Manifesto] looks like a last-ditch literary excursion to attack something fundamentally visual.’

Bernard Smith (photo via University of Queensland)The idea of a literary provenance or comparison here is interesting. Smith quite often shows a lively awareness of the incipient parallels between art and literature and their Australian discontents. Henry Lawson and Joseph Furphy both wrote ferociously about the importance of Australian language, Australian figures, and Australian description in fiction. In Place, Taste and Tradition, Smith mentions the kind of links that might usefully be drawn between Frederick McCubbin and Lawson – ‘desire for realism … forthright championing of the art of his country, and [a pervasive] note of sentimentalism’. In a discussion at a 1976 conference at Exeter University – ‘Readings in Australian Art’, recalled here by Emma Hicks – Smith quoted appreciatively from Furphy’s withering attack in Such Is Life (1903) on Henry Kingsley’s ‘slender-witted, virgin-souled, overgrown schoolboys who fill [his] exceedingly trashy and misleading novel with their insufferable twaddle’. What especially interested Smith were Lawson’s rejection of turning an outback ‘hell’ into a ‘heaven’, his insistence on ‘describing [something] as it really is’, and Furphy’s addition of the word ‘misleading’ to his litany of castigation.

Bernard Smith (photo via University of Queensland)The idea of a literary provenance or comparison here is interesting. Smith quite often shows a lively awareness of the incipient parallels between art and literature and their Australian discontents. Henry Lawson and Joseph Furphy both wrote ferociously about the importance of Australian language, Australian figures, and Australian description in fiction. In Place, Taste and Tradition, Smith mentions the kind of links that might usefully be drawn between Frederick McCubbin and Lawson – ‘desire for realism … forthright championing of the art of his country, and [a pervasive] note of sentimentalism’. In a discussion at a 1976 conference at Exeter University – ‘Readings in Australian Art’, recalled here by Emma Hicks – Smith quoted appreciatively from Furphy’s withering attack in Such Is Life (1903) on Henry Kingsley’s ‘slender-witted, virgin-souled, overgrown schoolboys who fill [his] exceedingly trashy and misleading novel with their insufferable twaddle’. What especially interested Smith were Lawson’s rejection of turning an outback ‘hell’ into a ‘heaven’, his insistence on ‘describing [something] as it really is’, and Furphy’s addition of the word ‘misleading’ to his litany of castigation.

Smith’s essays and excerpts in Antipodean Perspective reveal the precision and persuasiveness of his critical writing, but also his imaginative flexibility and assured range. The difference, for example, between the prose of his ‘Marx and Aesthetic Value’ (‘Can it be shown, within the presuppositions of historical materialism, that aesthetic value is invariably present in one kind or another in all material production …’) and this from The Boy Adeodatus (1984):

One fine day Mumma Parky came to see them all before she went away to Queensland. She wore a white cotton dress with a frilly neck, her long hair was divided across her forehead and swept up in a bun at the back. Bertha served tea in the garden and Olive Solomon, the photographer from the Boulevarde, was called in for the special occasion. Bennie stood on the folding chair in his velvet jacket, patent leather shoes and white socks. ‘Why don’t you wear this ring, Rose’, said Mum Keen, ‘it will look better’. Behind them was the sweet loquat.

The adjustment of tone and the addition of a detailed, painterly perspective that has taken place between the Marx and the memoir are effortless and perfectly judged. Likewise, Smith’s exquisite description of Hodges’ View of Point Venus and Matavai Bay looking East: ‘Painting into the eye of the light …’ Having successfully and creatively taken every possible liberty with the recognised Festschrift format, this collection concedes to custom in its conclusion with Emma Hicks’s excellent ‘A Distant Relationship’, describing her first meeting with Bernard Smith and also, as it happens, my own, at Peter Quartermaine’s ground-breaking ‘Readings in Australian Art’. Smith, as remembered, is fascinating and magnetic, an inimitable, stylish, and daring intellectual, a true original among his celebrants in Antipodean Perspective, who do him proud in different voices.

Comments powered by CComment