- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This book is suspended from a question mark, and all of Australia’s history is suspended with it. Henry Reynolds has been doing it for twenty years. What happens if we try to understand the coming of the Europeans from the Aboriginal viewpoint, from the other side of the frontier? Did the European invaders really think they were occupying a country that belonged to no one, a terra nullius? If we, the white people, had a legal title, how did we acquire it? If everything was fair and above board, why then this whispering in our hearts? And if so many big questions were left unanswered, if so many black people died so that we could live in prosperous comfort, Why weren’t we told?

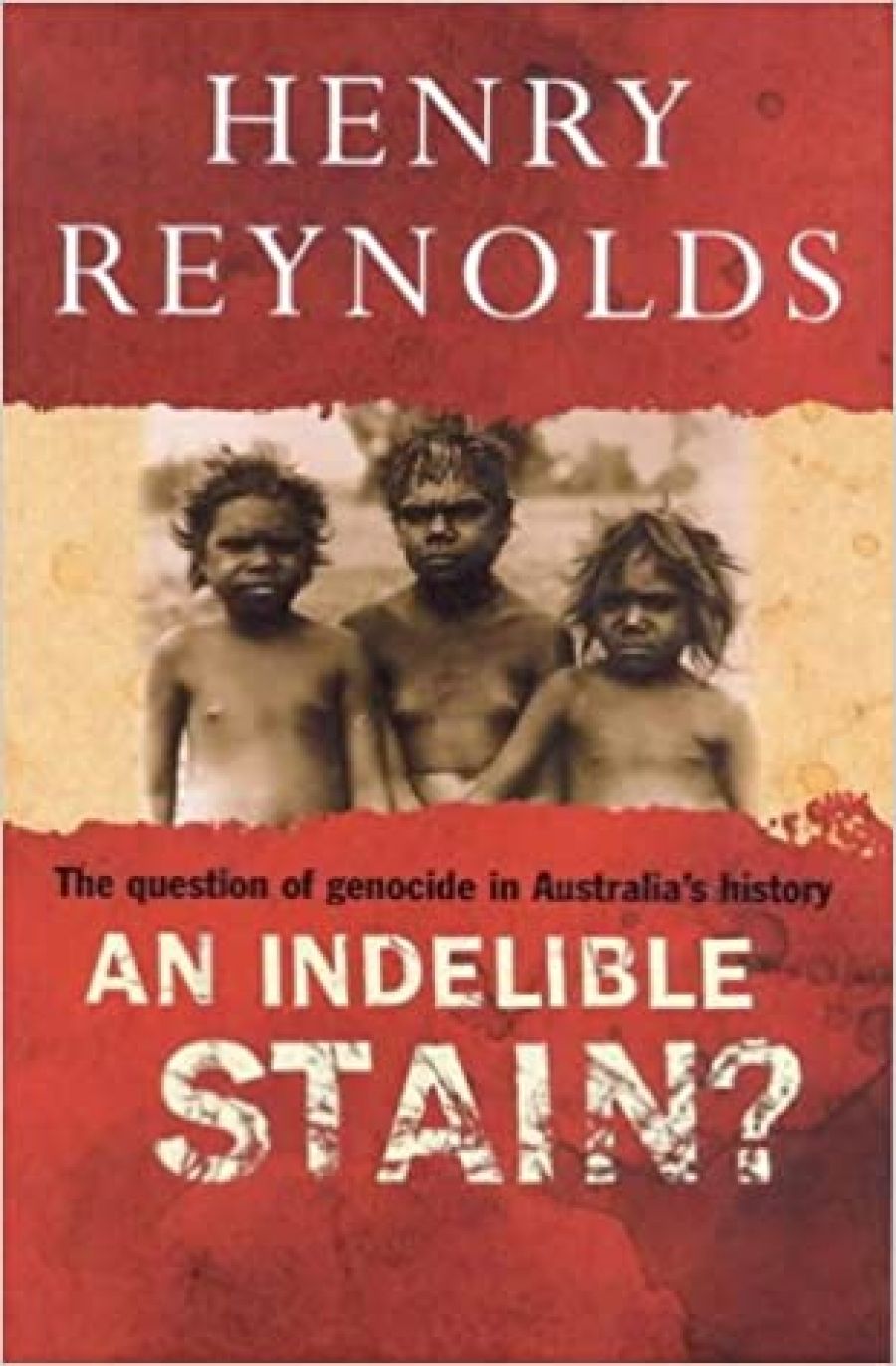

- Book 1 Title: An Indelible Stain?

- Book 1 Subtitle: The question of genocide in Australia’s history

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $30 pb, 217 pp

The reports by white observers do not tell a different story from the Aboriginal one. In an earlier book, Frontier, Reynolds directly asked the question ‘Was it genocide?’ and left open key parts of his answer. It could depend, he noted, on what might have been said around the Governor’s dinner table. Here he is again careful to document what can be documented and not to proceed beyond the evidence. Many references to massacres were published at the time. There was lively debate in public meetings and in the press about the rights and wrongs of armed expeditions against the Aborigines. Some (this would matter at the Hague court) were carried out under the direct authority of the Crown. More often the Colonial Office, in far away London, deplored what was going on. Many of the worst atrocities, carried out by the Native Mounted Police, occurred after the British Government surrendered responsibility for Aborigines to the colonists whose views and actions were well known. Of the frontier war, Mary Durack wrote:

Every traveller brought rumours of increasing trouble and many settlers now openly declared that Western Queensland could only be habitable for whites when the last of the blacks had been killed out – ‘by bullet or by bait’.

The Victorian Protector William Thomas was told his work was pointless because there would be no peace ‘till the Blacks are extirpated’. One of the wealthiest squatters said to him that not a single man would go on a mission merely to pacify the Aborigines, ‘but if I would go in search of them with the intent to exterminate them I would undertake that I could get 30 at least of men in the surrounding district who would willingly volunteer in the service’. The heat of the posse carried a cold self-interest. The alternative, said a Queensland paper, was ‘the abandonment of the country which no sane man will pursue’.

It is still a widespread attitude in Australia: should we have just packed up and left? And since we didn’t leave, Aborigines had two chances. One was to survive as best they could in a strange and hostile environment. The other was tidier. Within fifty years of settlers reaching a district, they noticed that the Aborigines were no longer there, whole peoples had disappeared. The ‘denial of the right of existence of entire human groups’ – not necessarily all Aborigines everywhere – was what the United Nations a century later called genocide.

Some in Australia who resist the idea of genocide in their own country make much of the exact terms of the United Nations’ definition, and the events that led to its adoption. Isn’t it obvious that what happened here was nothing like the efficient German killing of six million Jews? It is obvious, and the attempt Reynolds makes to lead back from the post-World War II drafting of the Genocide Convention into the earlier wars for the possession of Australia will not cut much ice with those who deploy the Holocaust to block off recognition of genocide closer to home. Germans have to deal with genocide; we don’t.

The killing got under way early; the later, apparently benign policies were the follow-up. For a small cultural group, massacre could, and was intended, to mean extinction. Many more groups were extinguished by disease, and others (after infection with venereal disease) by failure to reproduce. The conventional response to this demographic disaster has always been, ‘Who could be blamed for that?’ The susceptibility of indigenous peoples to European diseases, here as in the Americas, has been a favourite way of dismissing any European responsibility for the main cause of death. The smallpox epidemic that devastated Aboriginal peoples far beyond Sydney after the arrival of the First Fleet has been a matter of controversy before. Could the virus have been released on purpose? Reynolds thinks we should re-check the evidence.

The tragedy of Tasmania is re-examined in terms of the key judicial term ‘intent’, and as ‘inevitable necessity’. The killing times left the same questions as the frontier expanded to the west, the centre, and the north. But the story was not over once the blood dried on the frontier. There were steps that led to the stealing of children. The later, now more discussed genocidal policy of ‘breeding out the colour’ is firmly contextualised in what went before. Without the earlier assault, we can clearly see, there would be no collapse of traditional society, no half-caste ‘problem’, and no anxiety about a solution. When the Aborigines failed to die out, and just when Europe was about to learn how radical solutions could be, the responsible official from Western Australia posed his own question to a 1937 conference:

Are we going to have a population of 1,000,000 blacks in the Commonwealth, or are we going to merge them into our white community and eventually forget that there ever were any Aborigines in Australia?

That is why children had to be removed, and why Paul Hasluck’s postwar policy of assimilation could not so easily escape the racism from which it had sprung. An aim that had been plainly genocidal, ‘even if the practice fell far short of the awesome objective’, transmutes into a policy that will finally accommodate difference.

In so many ways, Australians accommodate difference with easy generosity. Why has it proved to be so hard to deal with the most determined assertion of difference: the insistence of Australia’s indigenous peoples to a special place? We will go as far as ‘reconciliation’ provided we do not have to recognise prior possession and the hard facts of dispossession. Least of all do we want to recognise genocide.

It is not the case (as readers of Raimond Gaita’s essay in the July 2001 issue of ABR might think) that there has been a long and deep discussion of genocide in Australia. There has been hardly any, and most of it has been side-tracked by a debate that focuses only on the stolen children. I find myself somewhere between the wide scope of the Genocide Convention and the ‘show me your murders’ of Inga Clendinnen. There are enough murders on the record, even if the murderers were unlikely to be brought to justice. The problem – Reynolds devotes much attention to this – has been in connecting the killing with those in authority who condoned or failed to stop it. To connect the earlier ‘dispersals’ with the later ‘dying race’ policies is also crucial, and it is not anachronistic to examine both in the light of a concept which, like many other tools we use, was not invented when the actions took place.

Melbourne and its millions whirl around me as I write. James Dredge, another Protector of the Aborigines in the ‘Australia Felix’ that would become Victoria, was told by one of them in 1840 about the quietness that had already fallen. ‘Blackfellow by and by all gone, plenty shoot’em, whitefellow – long time, plenty, plenty.’

Reynolds takes risks with this book. Not all of them will be covered by the question mark. Some people, he knows, are outraged that the term genocide should ever be used with reference to Australia; others are appalled that frank recognition of what happened can still be suppressed. I’m not sure that those of us who have sought to put genocide on the agenda deserve to be called ‘genocide promoters’ (as opposed to ‘genocide deniers’) but at least the idea is now centre-stage. Reynolds’s concern with intentions should remain a talking point as well. In the longer run, it will help us get to grips with a historical process in which intentions, responsibilities, and unintended consequences overlap. Then we can worry less about defining genocide, and deal more forthrightly with the consequences in understanding ourselves.

Comments powered by CComment