- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

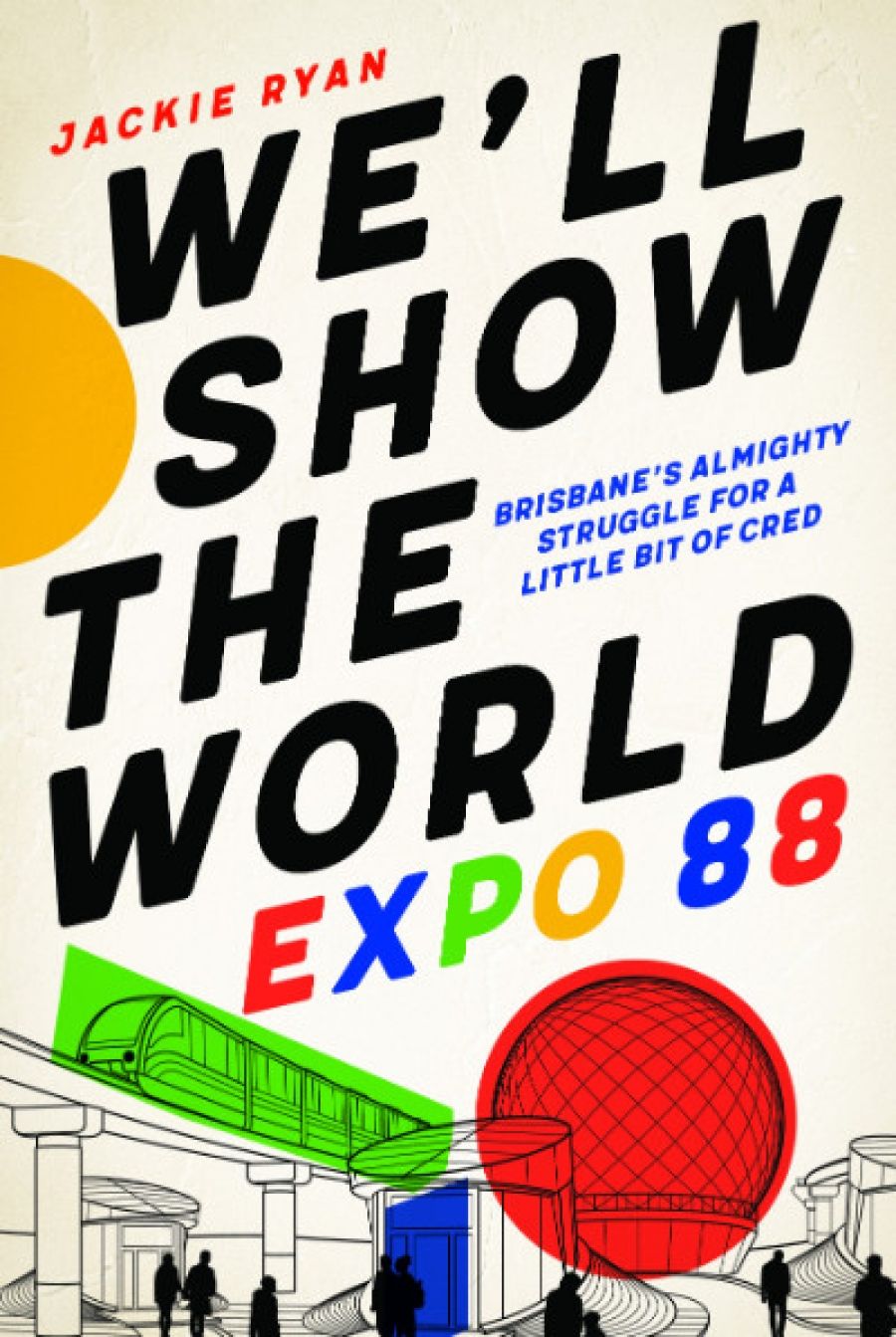

- Custom Article Title: Lyndon Megarrity reviews 'We’ll Show the World: Expo 88' by Jackie Ryan

- Custom Highlight Text:

Born in 1825, Brisbane is an elderly lady who has been to a surprising number of ‘coming of age’ balls. Numerous historians, officials, speechmakers, and journalists for several decades have implied that Brisbane (as of 1982, 1988, or whenever) is now not only the belle of the ball, but she ...

- Book 1 Title: We’ll Show the World: Expo 88

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $32.95 pb, 304 pp, 9780702259906

The author provides some useful historical context on world expositions since the Great Exhibition of 1851, highlighting their usefulness for exchanging new ideas across the world while also promoting the host city and boosting its self-image. By 1928, a Bureau of International Expositions (BIE) had formed, which assumed control of the process of selecting competing national bids for hosting such events. The Whitlam government signalled to the BIE that Australia was interested in holding an Expo in 1987/88. Ironically, Whitlam’s initiative ultimately led to his greatest political enemy, Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, winning a ‘Queensland victory’ when Brisbane secured the right to host Expo during the bicentenary of Australia.

Ryan skilfully weaves a series of interviews with key figures behind Expo’s organisation into a narrative highlighting the passionate intensity with which those entrusted with putting on Expo worked to get it ‘right on the night’. Expo chairman Sir Llew Edwards and former Queensland Premier Mike Ahern are among the many interviewees who shared their memories and insights with the author. Despite many anxieties, Expo 88 proved popular with the people of Brisbane, so much so that many repeat visitors were suffering from ‘post-Expo-itis’ after its closure. It was certainly a feast for the senses, with regular international musical and dramatic performances, fireworks, pavilions promoting participating countries, nearby blockbuster art displays, parades, and (to Australians at the time) exotic food experiences such as Japanese cuisine. Situated on the south bank of the Brisbane River near the CBD, Expo 88 coincided with a rediscovery of the river as a civic asset. This was reflected in the subsequent official decision to retain much of the former Expo site as a recreational area, including an artificial beach popular with families.

Expo 88 gave Brisbane a civic boost and sense of self-pride at a time when much of the national news about Queensland itself was about the Fitzgerald Inquiry, in which police and government corruption were centre stage. Because many official and commercial figures associated with the Bjelke-Petersen government played a part in the organisation of World Expo, Ryan gives the reader some useful background on the Bjelke-Petersen era and the frequently arrogant, unconventional way politics and business were conducted in Brisbane during the 1980s. She provides an entertaining, if discomforting, guide to a bygone era.

A panorama view of the stage and Brisbane River during World Expo 88. (Photo by Brisbane City Council)

A panorama view of the stage and Brisbane River during World Expo 88. (Photo by Brisbane City Council)

Pre-Expo Brisbane is largely presented in this book as an unsophisticated hick town, a cultural desert dominated by the authoritarianism, conservatism, and corruption of the National Party government led by Bjelke-Petersen between 1968 and 1987. Reflecting on Brisbane in the 1980s, Ryan writes: ‘It could be argued that Brisbane was not in need of renewal, since the city had not really begun.’ This statement does not bear scrutiny. While a lack of critical mass and the economic/cultural dominance of the southern capitals traditionally held Brisbane back, the initiatives of the Queensland government, the local council, and others between the 1960s and 1980s turned Brisbane into a modernising capital city that was far from a cultural desert. Tertiary opportunities were expanded, recreational facilities such as libraries and swimming pools were built, major road infrastructure projects were completed, more and more children finished secondary education, mainstream books were published by Jacaranda Press and University of Queensland Press, new performance venues such as La Boite and the SGIO theatre attracted audiences, and Brisbane was on the circuit of many international acts such as the Beatles and Bob Dylan. Brisbane by the 1980s was thus an emerging city rather than a nascent one.

The free Monorail at Expo 88 held in Brisbane from April to October 1988. (Photo by Lance)

The free Monorail at Expo 88 held in Brisbane from April to October 1988. (Photo by Lance)

Offering a smorgasbord of fresh sights, sounds, and tastes, Expo 88 was an undeniably special occasion for many Brisbane people. Nevertheless, the author’s contrast between the old Brisbane and the new post-Expo Brisbane inadvertently exaggerates the town’s cultural isolation in the 1980s and seriously discounts local exposure to new ideas through film, magazines, television, and other media.

Did Expo 88 bring about Brisbane’s coming of age? This seems doubtful, but the event did, at the very least, symbolise the city’s transformation into a global metropolis ‘by the river’. Ryan’s book affectionately captures Brisbane’s love affair with Expo, and it will make Queenslanders of a certain age feel agreeably nostalgic. We’ll Show the World is also a fitting tribute to the men and women who made Expo happen.

Comments powered by CComment