- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Geoffrey Blainey reviews 'Pompey Elliott at War: In his own words' by Ross McMullin

- Custom Highlight Text:

General ‘Pompey’ Elliott was a famous Australian in 1918, half forgotten seventy years later, and is now a national military hero. This Anzac Day he stood high. On French soil he was praised by France’s prime minister, Édouard Philippe, in one of the most mesmerising and sensitive speeches ever offered by a European leader to Australian ears ...

- Book 1 Title: Pompey Elliott at War

- Book 1 Subtitle: In his own words

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $59.99 hb, 544 pp, 9781925322415

Son of a battling farmer, Pompey interrupted a distinguished law course at Melbourne University in order to fight as a trooper in the Boer War. As a citizen soldier, he became a high-ranking officer in World War I. He kept a vivid diary and wrote numerous letters to his wife and two children; this large book is a selection of his wartime writings.

On 25 April 1915 he was rowed ashore at Gallipoli, where the narrow beach and the white cliffs reminded him of ‘Sandringham at home’. Shot in the ankle on the first day, he was shipped to Egypt, all the time deploring the scarcity of doctors. Returning to the war zone, he was quick to praise his Australian soldiers. To his wife, Kate, he wrote: ‘Fancy seeing a man you knew blinded and with both hands blown off trying to get up on his feet.’ In the intense fighting at Lone Pine in August 1915, four of the seven Australian VCs were won by soldiers in his battalion.

Reaching the French frontline almost a year later, Elliott saw the huge opposing armies unable to break a long stalemate caused by the deadliness of their own artillery and machine guns. Those weapons were so lethal that it was almost impossible for troops to advance the short distance between their own trenches and the enemy’s. Privately he confided that the sound of the big guns ‘is continuous by night and by day’. Resembling ‘the roar of the seas in a storm breaking on a rocky coast’, the din was so overpowering that the ‘drums of one’s ears seem to be continually vibrating to the quiver of the air’. His wife must have been worried by his casual message that fellow officers in the trenches ‘take no more notice of the bursting shells than one does in Melbourne of the passing tram bells’.

Elliott is often observant, like his skilled biographer Ross McMullin. There is a touch of the romantic in some of his letters, written when his soldiers were camped somewhere behind the main fighting zone: ‘it was a wonderful sight last night to see the camp fires of this vast army blazing east and west and north and south like the lights of some huge city, whilst on three sides the glares from the guns lit up the sky like gleams from distant lightning’. To Jane he described the tents capping the ups and downs of the landscape like ‘the pictures of old digging days of Ballarat and Bendigo’.

As winter approached, his diary recorded rain and mud: ‘My poor boys had a terrible time in the trenches. For the 3 days and 2 nights they were there they had practically no sleep or rest, for the trenches were two or three feet deep in water.’ In December the severe frost froze the toes of many of his soldiers who, standing up, tried to sleep by leaning against the firm sides of the trenches.

Elliott relished his letters from home, though they could be two months old when they arrived. Even on the narrow battle zone, the news travelled slowly. After his wife’s brother, not far away, was killed by a sniper’s bullet, the news did not reach Pompey for almost three weeks: ‘It is with a sad heart that I write to you again, my poor darling wife.’ Constant is his concern for his own soldiers and their health, their wounds. On the other hand, he despises some Australian soldiers: ‘there are cowards, curs and shirkers who clear out and leave their mates in the lurch’. He would like to shoot them but under ‘the Commonwealth law we cannot touch them’. He is quietly pleased when his own soldiers visit farms a few miles from the trenches and help the French women by digging potatoes. Disliking German soldiers, he usually called them ‘The Bosche’, a sneering slang phrase. He feels sure that if Germany wins the war it will regulate Australia, intervening harshly if necessary. I have the impression that today we cannot conceive how a German victory might have affected Australia.

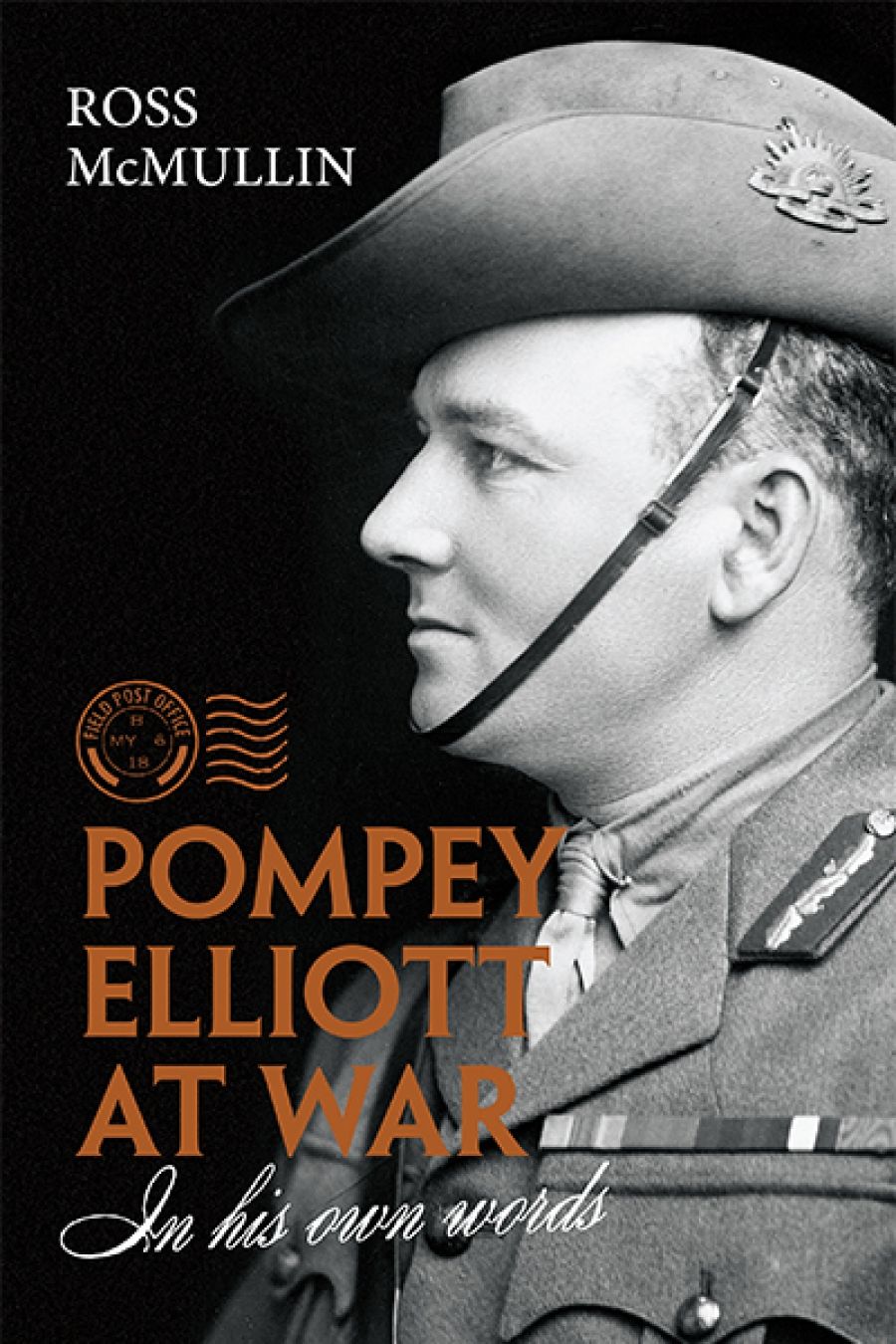

Portrait of Brigadier General H.E. 'Pompey' Elliott, ca. 1920 (Australian War Memorial, Wikimedia Commons)

Portrait of Brigadier General H.E. 'Pompey' Elliott, ca. 1920 (Australian War Memorial, Wikimedia Commons)

The war over, Elliott stood for the Senate, topping the Victorian poll in the federal election of 1919. He continued to practise as a solicitor, but began to suffer from war-induced stress. In 1931, attacking his left elbow with a razor, he committed suicide.

He received one slice of luck long after he was dead. He was found and brought back to life by an impressive historian.

Comments powered by CComment