- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Philosophy

- Custom Article Title: William Poulos reviews <em>How To Keep Your Cool</em> by Seneca and <em>How To Be a Friend</em> by Marcus Tullius Cicero

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Serenity now,’ repeated Seinfeld’s Frank Costanza whenever his blood pressure got too high. His doctor recommended this anger-management technique, but he might as well have got it from Seneca, whose De Ira (Of Anger) James Romm has edited ...

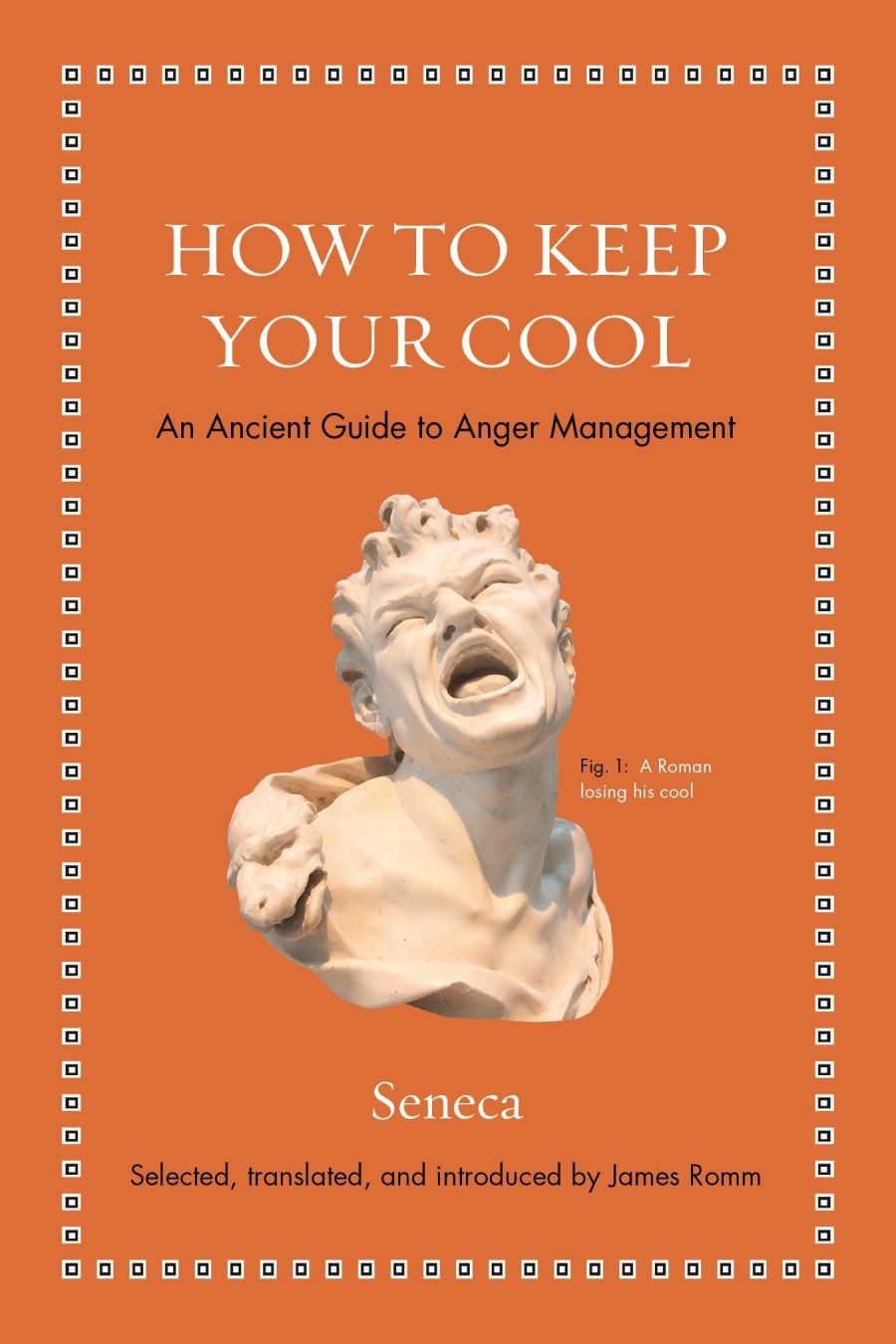

- Book 1 Title: How To Keep Your Cool: An ancient guide to anger management

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press (Footprint), $29.99 pb, 240 pp, 9780691181950

- Book 2 Title: How To Be a Friend: An ancient guide to true friendship

- Book 2 Biblio: Princeton University Press (Footprint), $29.99 pb, 208 pp, 9780691177199

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

.jpeg)

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

.jpeg)

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2019/August_2019/640 (1).jpeg

Later, his tone becomes a little indignant: ‘I don’t understand why self-control is so difficult, since I know that even tyrants, their temperaments puffed up by both wealth and power, have suppressed the harshness that comes naturally to them.’ (Seneca wrote a whole treatise praising the mercy of the young Emperor Nero. I couldn’t believe it either: I had to check the Latin.)

Maybe I shouldn’t be too hard on the old fellow; most of his advice is sound, even some two thousand years later, and his recommendation to have calm and humble friends is timely.

Writing about ninety years before Seneca, Cicero also avowed the importance of friendship, saying that, except wisdom, the gods had given ‘nothing better to humanity’. Aristotle distinguished three bases for friendship: utility, pleasure, and virtue. Cicero recognises virtue as the only basis for friendship; we are friends with someone only because we admire his or her qualities:

We are not kind and generous to our friends because we seek favours in return. We are not so petty as to charge interest on our kindness. We are kind-hearted because it is the right and natural thing to do, not because we are hoping for something in return. The reward of friendship is friendship itself.

People who judge something by the amount of pleasure it gives them are ‘like cattle’ and will never raise their low thoughts to anything ‘lofty, noble, and divine’. Cicero says friendship only exists between good people because it depends on loyalty, integrity, and generosity. You should never do something wrong for the sake of friendship; if a friend asks you to, he may not be the sort of person you want around.

Both books are from Princeton University Press’s series Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers. The translations are accurate and fluent but could have done more to reveal the flexibility of the Latin language. Romm has Seneca say: ‘human nature contains treacherous thoughts, ungrateful ones, greedy and wicked ones’. Seneca wrote fert humana natura insidiosos animos, fert ingratos, fert cupidos, fert impios. He repeats the verb fert and puts it at the beginning of every clause – an emphasis which sticks out like a tutu in the bush, though you wouldn’t know it from the translation. Romm further weakens the emphasis by adding an ‘and’, and by translating fert as ‘contains’, though ‘bears’ is richer and more accurate.

This is a problem with the series: it refuses to emphasise that the Romans were not like us. Don’t forget that they branded runaway slaves on the forehead. Oh, and they had slaves. The principle of this series is that the world is in trouble (O tempora! O mores!) and Roman philosophers can help us save it. Maybe they can, but they’re too busy taking selfies: although modernisation is not always modification, these editions come dangerously close to it because they give us the few parts of Roman thought we’re already comfortable with. Romm pretty much admits this in his introduction, revealing that the smudges on the face of ancient wisdom belong to Foucault, under whose model ‘ancient Stoicism has a salutary role to play in the modern world, as we seek remedies, at night in our quiet bedrooms, for the many ills of the soul’. This is a cartoon of ancient Stoicism, which asserts the need for a public life and an affiliation with the world.

Invoking ancient philosophers while refusing to grapple with their ideas merely produces books of Instagram Intelligence and Pinterest Profundity. Why must we abuse history for our own purposes? Can’t we learn from it without raiding it for slogans? Can’t I read anything without Foucault getting in the way? SERENITY NOW!

Comments powered by CComment