- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Wearne's world

- Article Subtitle: Doing the suburbs in different voices

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

The near-religious title of Alan Wearne’s new selection of poems, Near Believing, gives an impression of bathos and deprecation, while nevertheless undermining structures of belief, as represented in the book; at times this belief is explicitly Christian, but can also be seen more generally as belief in others, or in the suburban way of life. It is, then, while modest-seeming, highly ambitious – and, in another irony, further evokes the pathos, and hopelessness, of wanting to believe. In the title poem, which appears in the uncollected section, ‘Metropolitan Poems and other poems’, a ‘near-believer’ is defined by the poem’s priest speaker as ‘that kind of atheist I guess who prays at times’. This formula captures the ambiguity of the book’s many speakers and their addresses.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

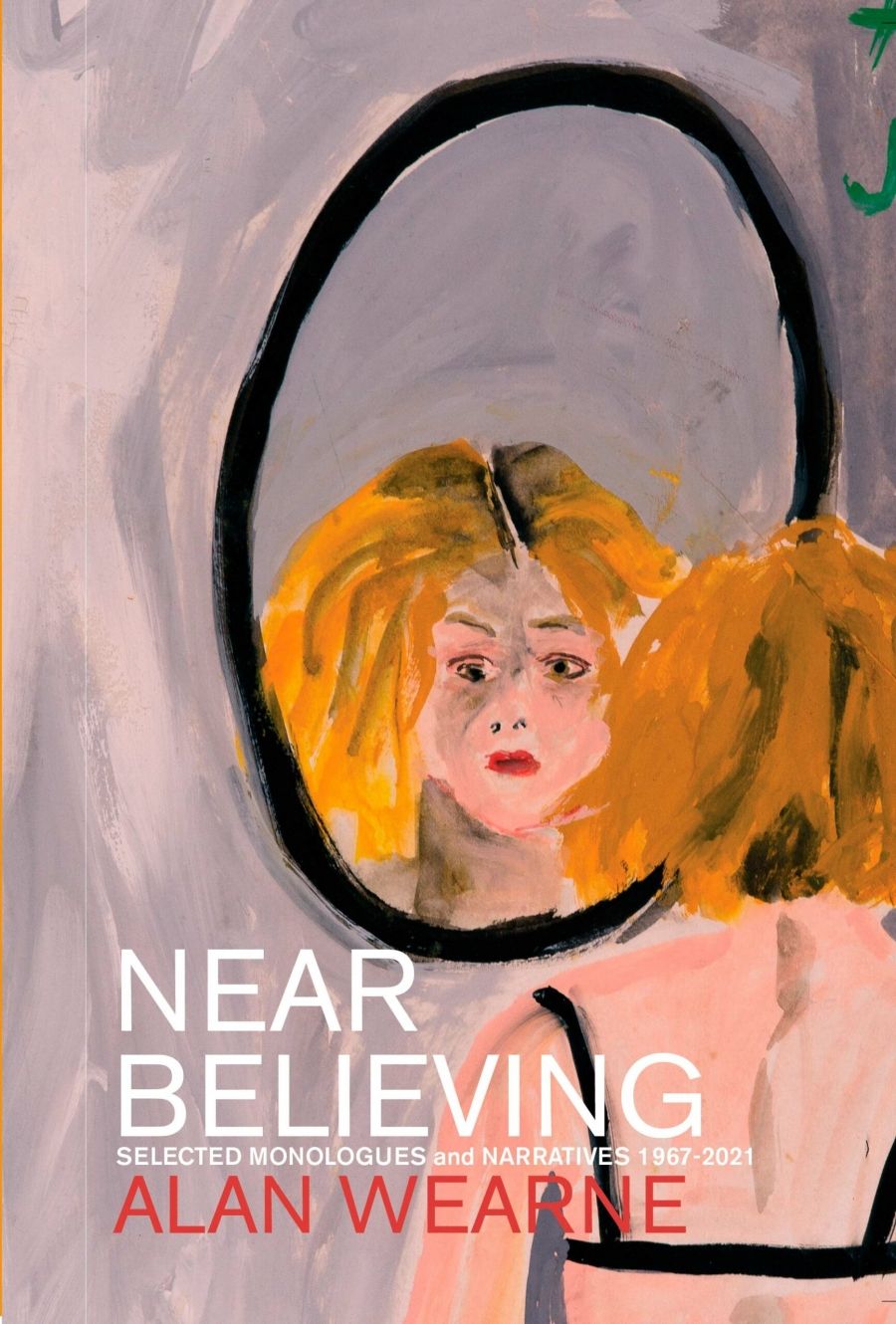

- Book 1 Title: Near Believing

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected monologues and narratives 1967–2021

- Book 1 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $29.95 pb, 252 pp

The book’s first section, consisting of six pages taken from Poems 1967–1974 begins with the remarkable, Bruce Dawe-like ‘Saint Bartholomew Remembers Jesus Christ as an Athlete’, written when Wearne was eighteen. According to one legend, Saint Bartholomew’s conversion of the king of Armenia to Christianity so enraged the king’s brother that he ordered the apostle be skinned alive and beheaded. Bartholomew also has a massacre named after him: the sixteenth-century bloodbath in Paris. But all this is outside the poem. The pertinent death, or political murder, is that of Christ himself, described by Wearne in probably the wryest, most understated terms ever: ‘his arms / were raised once more; his feet, however, broken; sort of enforced retirement’.

Concision without density is another Wearne hallmark, as seen in another early poem, ‘St Kilda’, a poem of end rhyme (first stanza ABCB, second ABAB, third ABCB), with disparate sex descriptions concluding its first and second stanzas. In the first, ‘the mercury broiled ninety / whilst Brookes and boy-friend made it in the sand’ (‘made it’ illegally is worth noting). In the second, ‘And bless you a quiet hometown-even, fucking / I hope with those boots (large, impractical) off!’ After these first two monologues we arrive in more complicated territory. ‘Warburton 1910’, voiced by a newlywed woman, is littered with quotes, including the term ‘newlyweds’, which appears as an ironised, rather than an attributed, term: a quote from the ethos. ‘Eating Out’ is a smorgasbord of voices, sounding somewhere between the Henry Lawson of ‘The Shanty on the Rise’ (Wearne has been called the ‘Lawson of the suburbs’), and Ronald Firbank. Radio and repetition have the last words: ‘it smarmed away its “Happy day, happy day”’. The poem also includes the tonally confident sentence: ‘Nice / nice nice nice.’

The book has eight epigraphs, including quotes by Wallace Stevens, Jean Cocteau, Ivan Turgenev (to Henry James), and Cole Porter: allowing for the only Australian reference, ‘There’s an old Australian bush song / Melba used to sing’. These are followed by Michelle Borzi’s excellent introduction, which begins with a ‘characteristic’ Wearne quote: ‘I like raiding this country for its potential to write about. I do like the idea of being moderately uncompromising, if such a thing exists, in the Australian potential of my poetry.’ Borzi suggests that Wearne finds the potential of a suburban street ‘mindblowing!’, and further proposes that Wearne aims at a temporal dialogue between his poems, set in the past, and the present moment (as in Christ’s ‘forced retirement’). Further apt quotes are taken from Wearne interviews, including a note on influences: Geoffrey Chaucer, Robert Frost, Kenneth Koch, Robert Browning predictably; also, Arthur Clough and George Meredith. A sonnet from the verse novel The Lovemakers (2001) demonstrates the influence of all three Victorians – and exemplifies what preposterous neologisms end rhyme can produce: by sonnet’s end the subject of the poem (the speaker’s wife’s lover), dubbed by him ‘Wonderboy,’ becomes ‘Wonderchook’ (‘Wonderchook’s’ rhyming with ‘y’dooks’, as in, put them up); the final word, rhyming with ‘fit’ and other conventional ‘-it’ words, is ‘wondergrit’, presumably a dehydrated food that men-hens eat. Borzi describes Wearne’s use of interruption in his poems (voices often interrupt each other, or, a voice interrupts its own line of thought: compare Chaucer ‘And I seyde his opinion was good / What!’) as ‘almost a method’, which creates, and alters, the poems’ moods, and their music.

Violence is not necessarily destructive, implies the Browning-esque narrative sequence Out Here (‘out here’ being Wearne’s conception of a suburban never-never). The sequence’s first poem, ‘Yes “Just …”’, is voiced by a woman teacher, who relays the information that a student, Brett Viney, has slashed his own stomach. Brett says that he was just ‘mucking around with the knife’. But the explanation doesn’t suffice, and the extract’s five speakers, of a poem each, circle around this generative act, as if the stabbing is like the slap, in Christos Tsiolkas’s much later novel. The second poem, ‘Home’, spoken by Brett’s estate agent mother, Marian, sounds (Gig) Ryanesque, braiding Ryan’s cadence with Wearne’s diction for an idiosyncratic female voice: ‘I’ve work, pocket money and / where we can begin, homes.’ Wearne’s speakers live through their echoing of each others’, as well as literary, voices: Marian’s ‘And should I continue?’, evoking T.S. Eliot. In lyric poetry, this would be merely allusive, but in dramatic monologue, it suggests a dialectic relation between the poet’s creation of character, and the character’s creation of their own discourse.

The Nightmarkets provides a rhyme highlight: ‘Throat like an oven, phlegm like toffee, / those mornings Lou was busy, but Ian came: “Earl Grey? Coffee?’’. Excerpting narrative emphasises lyric form over story, like the sonnet quoted above, or the ‘Three Villanelles’, spoken by a QC, which commence The Lovemakers section. The QC avers, ‘My job requires plain speech’: which he then follows with a figurative reflection on the ‘puree / of perhaps and maybe’ of a now executed defendant’s situation. Near Believing is the perfect entry point into the everyday complexities of Wearne’s world. Just follow the voices.

Comments powered by CComment