- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

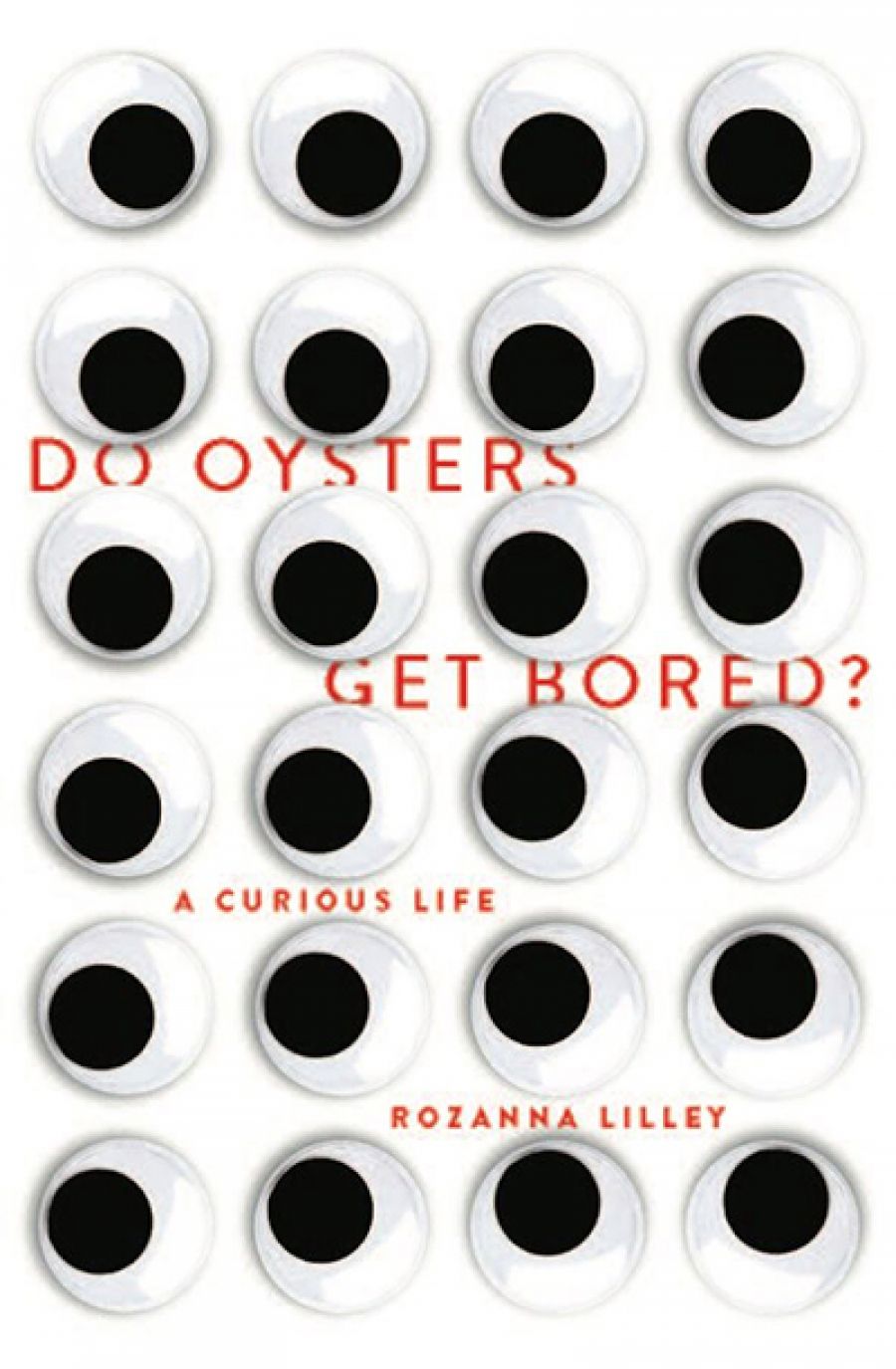

- Custom Article Title: Susan Sheridan reviews 'Do Oysters Get Bored?: A curious life' by Rozanna Lilley

- Custom Highlight Text:

At the centre of this book is Oscar, the son of Rozanna Lilley and her husband, Neil Maclean, and Oscar’s particular way of encountering the world. Unpredictably (by most people’s standards), he is indifferent to some things, sharply affected by others. His fears – of the outdoors, of night and the watching moon, of dogs ...

- Book 1 Title: Do Oysters Get Bored?

- Book 1 Subtitle: A curious life

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $29.99 pb, 228 pp, 9781742589633

Despite a diagnosis of ‘autism disorder’ when he was three and seemed to be linguistically disabled, Oscar eventually attends a regular school, has his friends to visit for a tenth birthday party, and reads his new comic encyclopedia with such excitement that ‘he paces the living room, flapping and groaning with pleasure’. As Lilley writes, her son is ‘in many respects an ambassador for this most modern of conditions’.

Oscar is intensely but selectively curious about a world that is shaped by his fears, but also by his fascination with words and his enthusiasm for making up stories drawn from his beloved game and television shows. I began to understand, as never before, how much an autistic person’s life may be shaped by fear, and to admire his parents’ dedicated, sometimes exasperated, attempts to deal both with their extraordinary child and the world’s perceptions of him. They value his difference, but refuse to romanticise it. As Lilley writes, ‘autism is a shooting gallery, a passing parade occupied by stereotypical figures created through a heady mix of prejudice, ignorance and voyeuristic fascination’.

A recent New York Times review of To Siri with Love: A mother, her autistic son, and the kindness of machines by Judith Newman, refers to ‘the fast-growing library of autism lit’, remarking that Newman’s book is distinctive in this context because, ‘As she removes the zone of privacy from herself and her family, she is edging into the world her son occupies.’ That is, she writes as if saying whatever is on her mind, however unconventional, even appalling, it may be.

Rozanna Lilley’s book has something of the same quality, candidly revealing her own phobias or her parents’ failings, as well as her son’s fears and demands. Indeed, it becomes as much her story as Oscar’s, as the stories move back and forth between her present family life and her memories of childhood, and her precocious and precarious sexual comings-of-age. The emotional terrain of the book’s present time is marked by her father’s decline into dementia and death, and grief for the loss of her mother some ten years earlier.

The memoir, made up of short prose pieces, is complemented by a collection of poems which expand on her memories, including some horrendous exploitative sexual encounters with older men. Allusions to Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath suggest their generic affinities with confessional poetry. Other poems touch on intensities of experience that can’t be sustained in daily life, offering a counterpoint to the world of the memoir.

This is indeed ‘a curious life,’ even given its focus on autism. There was never a safe ‘zone of privacy’ for this writer. Her parents were poet and dramatist Dorothy Hewett, one of the most talented writers of her generation, and her third husband, Merv Lilley, a rough diamond from rural Queensland who shared her passions for poetry and anarcho-communist politics. Rozanna and her sister Kate grew up in a chaotic libertarian household with Dorothy’s three sons from a previous marriage. Knowing something of the two great mythologisers who were her parents makes a disconcerting difference to the way we read Rozanna’s anecdotes of Dorothy’s carelessness, or Merv’s belligerence. Yet she maintains control over the way they appear in her book, imagining them finally in a suitably theatrical funereal tableau: ‘My mother holds a book of romantic verse in one chiselled hand and a cup of tea in the other; a rifle leans nonchalantly across my father’s leg as he whistles for his loyal kelpie.’

Rozanna Lilley

Rozanna Lilley

The book draws on hard-won self-knowledge. Lilley writes: ‘sometimes I suspect that it’s anxiety that really stitches us together, a complex web of half-remembered connections, of fears that stretch tautly to reinforce established thread’. Caught in this net, we mutter stories about heroes and demons, or count to one hundred, ‘the spells that keep us both safe from harm and distant from the incessant demands of the world’. This perceptive comment about the self and its strategies also serves as a marvellous image of the way these stories work.

The title piece, ‘Do oysters get bored?’ describes a family holiday at Patonga on the Hawkesbury River north of Sydney. Unimpressed by the place (‘nothing but islands and boats’), Oscar begins busily to think about the marine world: ‘If you were an oyster, would this entire place be the known universe?’ In the narrative the mother’s state of distress, arising from the wreckages of her own life, is the continuing undertone. Over this, the boy’s questions and observations (of the river: ‘It’s as flat as a book’) bring her moments of reassurance, like the spells. In some miraculous way, he provides her solidity, as she does his.

Comments powered by CComment