- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

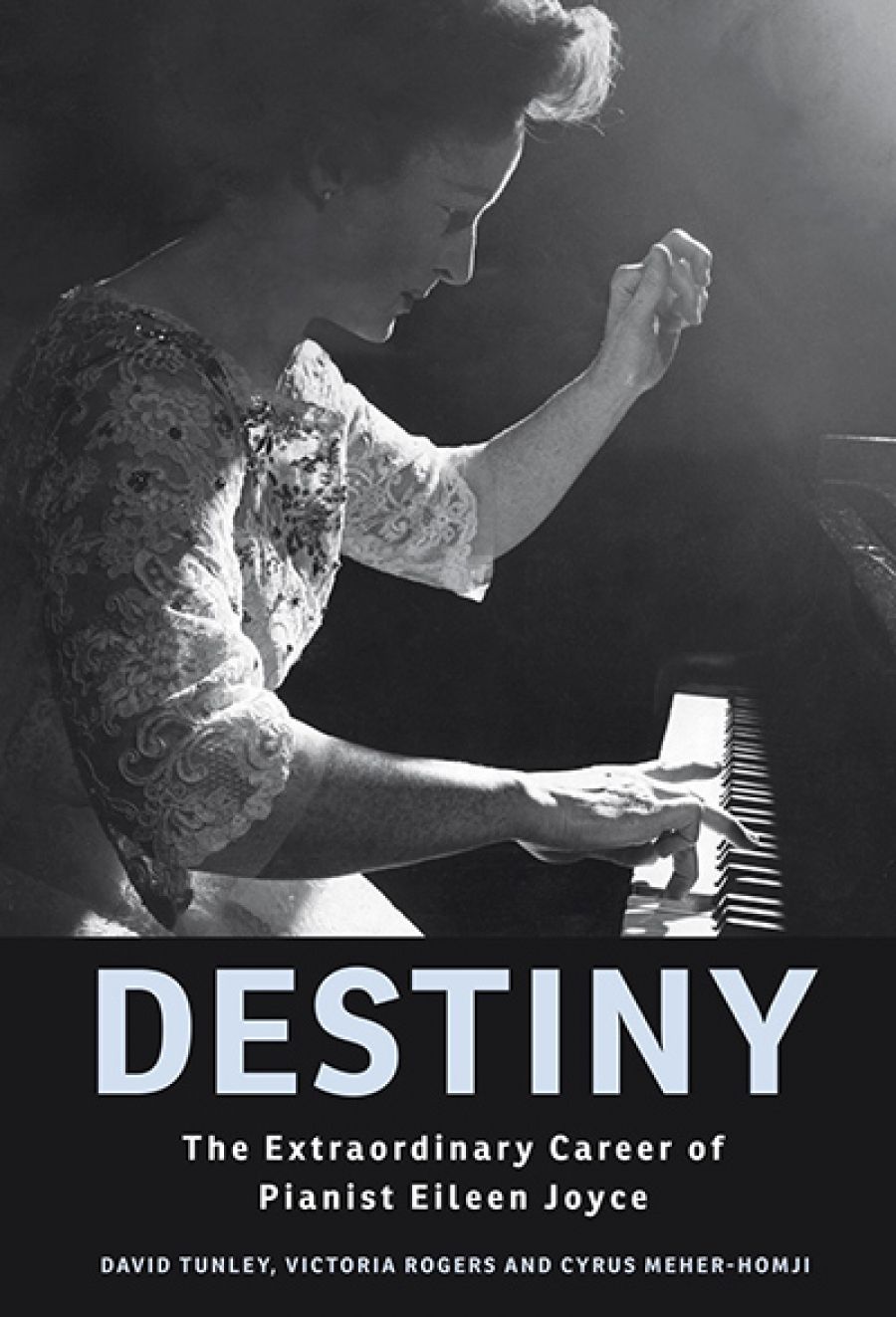

- Custom Article Title: Paul Watt reviews 'Destiny: The extraordinary career of pianist Eileen Joyce' by David Tunley, Victoria Rogers, and Cyrus Meher-Homji

- Custom Highlight Text:

Eileen Joyce’s name is not to be found in books about the great pianists, but a great pianist she was nonetheless. Born and raised in rural Tasmania and Western Australia, she studied in Leipzig and London and eventually found fame as a versatile pianist with an unusually robust technique and a wide repertory ...

- Book 1 Title: Destiny

- Book 1 Subtitle: The extraordinary career of pianist Eileen Joyce

- Book 1 Biblio: Lyrebird Press, $55 pb, 219 pp, 9780734037862

Biographers and critics of Joyce have struggled to find the right words to describe her playing and have been quick to either praise or condemn her interpretations. Some critics find her Mozart and Grieg recordings dull, but I found them energetic, precise, and rhythmically adventurous, if sometimes a trifle rushed. Most remarkable of all is her exceptional technique in passages of pianissimo: this might stem from Joyce’s habit of practising quietly on the keyboard – or away from it – to avoid annoying the neighbours.

Coinciding with the release of this set is a new biography of Joyce by David Tunley, Victoria Rogers, and Cyrus Meher-Homji. Richard Davis’s Eileen Joyce (2001) – thoroughly researched and honest about Joyce’s many personal foibles and failings – is a hard act to follow. However, this team of authors has given us a wider musicological framework in which to understand Joyce’s career.

The opening chapter, an overview of Joyce’s biography, relates the various musical cultures of rural Western Australia that might have been particularly influential on the young pianist. It provides a compelling picture of the vibrancy and eclecticism of the musical milieu in regional and remote areas that was not uncommon in the early part of the century. It is a timely reminder that Australia’s musical culture – both élite and popular, if they are the appropriate words to use – was not contained to capital cities.

Tunley’s chapter on the development of Joyce’s technique is an intriguing account of the theory and practice of piano technique that Australians such as Joyce encountered in local and imported training manuals. Tunley provides an excellent context in which the ‘weight’ and ‘rotation’ methods of technique were imparted to Joyce. Other Australian pedagogues such as Ignaz Friedman and Mack Jost also gave these techniques, in varying degrees of emphasis within their pedagogy, to generations of Australian pianists.

Eileen Joyce (Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons)Victoria Rogers provides a well-balanced account of Joyce’s life and career in London, and of the social and musical obstacles that stood in her way. Some of these obstacles Joyce was brazen enough to overcome by herself, such as in her assertive ploy to meet London’s leading piano pedagogue Tobias Matthay. Other circumstances Joyce could not control, such as waiting for invitations to come her way for such opportunities as her concerts with Sir Henry Wood and for the BBC.

Eileen Joyce (Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons)Victoria Rogers provides a well-balanced account of Joyce’s life and career in London, and of the social and musical obstacles that stood in her way. Some of these obstacles Joyce was brazen enough to overcome by herself, such as in her assertive ploy to meet London’s leading piano pedagogue Tobias Matthay. Other circumstances Joyce could not control, such as waiting for invitations to come her way for such opportunities as her concerts with Sir Henry Wood and for the BBC.

The repertory of the CD collection suggests that Joyce was not afraid to try new things. Her career as a harpsichordist is of especial note; also, her willingness to broadcast and perform for the cinema was risky for her reputation. After studying the harpsichord for a number of years and making her début she made an impression right away and performed regularly with fellow harpsichordists and early music enthusiasts and scholars such as Thurston Dart. However, her performances of music for the cinema (even Brief Encounter in 1945) were seen by some as ‘cheap’ and cast doubt on her seriousness as a concert pianist. Joyce was not deterred.

Meher-Homji provides the background of commercial and musical politics behind the recordings and their often-glowing appraisals in the press, particularly in Gramophone, but also details some of the less favourable reviews, especially of some of the piano miniatures. It is a surprise to hear that Joyce became a celebrity: even magazines such as Woman’s Day were reporting the commercial successes of her recordings. This media attention was no doubt carefully arranged by Joyce and her public relations team.

There is much good listening in the CD set and this latest Joyce biography is well crafted. Both projects leave one wishing that Joyce had recorded many more works and that more noted Australian pianists were the subjects of scholarly research.

Comments powered by CComment