- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

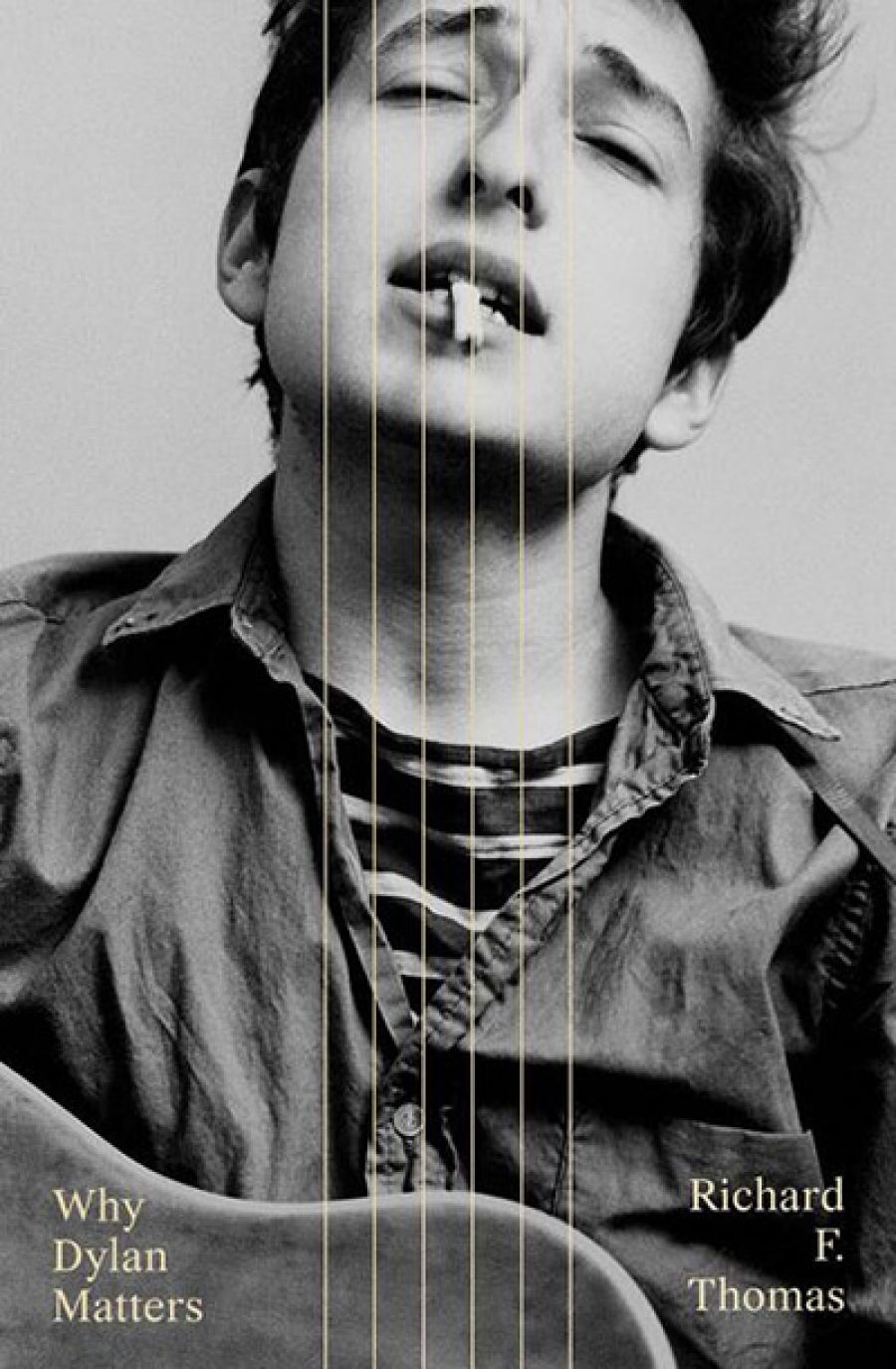

- Custom Article Title: James Ley reviews 'Why Dylan Matters' by Richard F. Thomas

- Custom Highlight Text:

There was a certain predictability to the arguments that flared when Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016. For the most part, they were variations of the arguments that have shadowed him from the beginning of his career, twisted echoes of a million late-night dormitory discussions about whether ...

- Book 1 Title: Why Dylan Matters

- Book 1 Biblio: William Collins, $24.99 hb, 368 pp, 978000824598

Galling though it appears to be to some of his detractors, the case for the latter is overwhelming. Dylan’s existence is one of the reasons it is no longer possible to speak of ‘literature’ in exclusive or generically narrow terms. The earnest brow-furrowing about him being a poet that started as soon as he began writing and recording in the early 1960s (and which was mocked by Dylan in the early song ‘I Shall be Free No. 10’: ‘I’m a poet / and I know it / hope I don’t blow it’) was really just a clumsy recognition of the fact that he was writing songs of such startling precocity that conventional distinctions seemed inadequate. Like all influential artists, Dylan created the conditions for his own reception, forced the culture to bend itself into a new shape that could accommodate his singular talent. Seen in this light, the decision to award him the Nobel Prize, though unprecedented, is a lot less radical than it looks. The Swedish Academy wasn’t unilaterally redefining the concept of ‘literature’; it was catching up with reality.

The large and ever-growing body of critical writing about Dylan’s work is a testament to its enduring fascination, but also to the intellectual respectability it has attained. As Richard F. Thomas observes in Why Dylan Matters, Dylan scholarship has become ‘part of the academic mainstream’. Thomas is himself a professor of Classics at Harvard University, who teaches a course on Dylan’s work on the side. In Why Dylan Matters, he situates his subject within literary tradition in the widest possible sense, arguing that Dylan is ‘part of that classical stream whose spring starts out in Greece and Rome and flows on down through the years, remaining relevant today, and incapable of being contained by time and place’.

In support of this claim, Thomas develops an argument about the nature of Dylan’s creativity, which he proposes is remarkable for its ‘intertextuality’. The force of this insight is somewhat diminished by the fact that Thomas doesn’t seem to know what intertextuality means. It is not, as he claims, ‘the creative reuse of existing texts’. As originally defined by Julia Kristeva, intertextuality is not an artistic practice; it is a property of all texts. It refers to the inherent plurality of language, the way in which texts will inevitably contain echoes of other texts because the creation of meaning depends on repetitions, formal conventions and pre-existing networks of reference. Whether these intertextual doublings are deliberate is beside the point. If intertextuality was simply a fancy way of referring to allusions and quotations, as Thomas claims, the concept would be redundant: we already have words for those things.

This lexical quibble aside, Thomas does identify an important feature of Dylan’s art. It has long been recognised that his songs are full of allusions and borrowed lines from all manner of sources. Critics such as Greil Marcus and Michael Gray have established just how deeply his work draws from the well of the folk and blues traditions that emerged from what Marcus called the ‘old, weird America’. Dylan’s creative practice is steeped in the fluidity of that folk culture, in which it is common for melodies and chord progressions and lyrics to be freely adapted or repurposed or transformed into entirely new works.

Dylan has done this more or less openly throughout his career. The tune of ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ is adapted from a slave’s lament called ‘No More Auction Block’; ‘Girl from the North Country’ is based on ‘Scarborough Fair’; ‘Maggie’s Farm’ is a ricochet from an old folk song called ‘Penny’s Farm’; ‘Blind Willie McTell’ takes its melody from the blues standard ‘St. James Infirmary’; the title track from Tempest (2012) rewrites an obscure Carter Family number called ‘The Titanic’. Many of Dylan’s later songs acknowledge their debts in their titles. ‘High Water’ is a tribute to Charlie Patton; ‘Sugar Baby’ was originally the name of a Dock Boggs song; ‘The Levee’s Gonna Break’ draws its inspiration from Memphis Minnie.

Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C., 1963 (Wikimedia Commons)

Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C., 1963 (Wikimedia Commons)

How you regard these kinds of borrowings, observes Thomas, ‘depends on how you think literature and art in general should work, particularly on whether you insist upon notions of “originality”, as if anything rooted in folk, blues, and poetry at large is ever wholly original’. There is a world of difference, he argues, between plagiarism and the creative process he calls ‘transfiguration’, which he explains with reference to the numerous allusions he finds in Dylan’s songs to the work of classical poets such as Ovid, Virgil, and Catullus. Thomas builds a compelling case that Dylan, who is notoriously cagey when it comes to discussing the meaning of his songs, has a longstanding interest in classical antiquity that dates back to his membership of the Latin Club at Hibbing High School. Why Dylan Matters proposes that his use of classical sources is not only purposeful, but that he wants them to be recognised, or at least sensed: he wants us to feel the ghosts of the past haunting the present.

T.S. Eliot’s famous maxim ‘mature poets steal’ came with an essential qualification: the good poet will transform what he takes ‘into something better, or at least something different’. Dylan has been doing this for more than half a century. Why Dylan Matters argues, with a welcome emphasis on his under-appreciated later work, that the essence of Dylan’s genius lies not simply in his linguistic flair or his deep appreciation of literary and musical tradition, but in his transformative recognition that there is nothing new under the sun, that in art all invention is reinvention, that a great song can conduct the expressive energies of the past in a way that reverberates across the centuries. In this quite literal sense, his greatest work is timeless.

Comments powered by CComment