- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

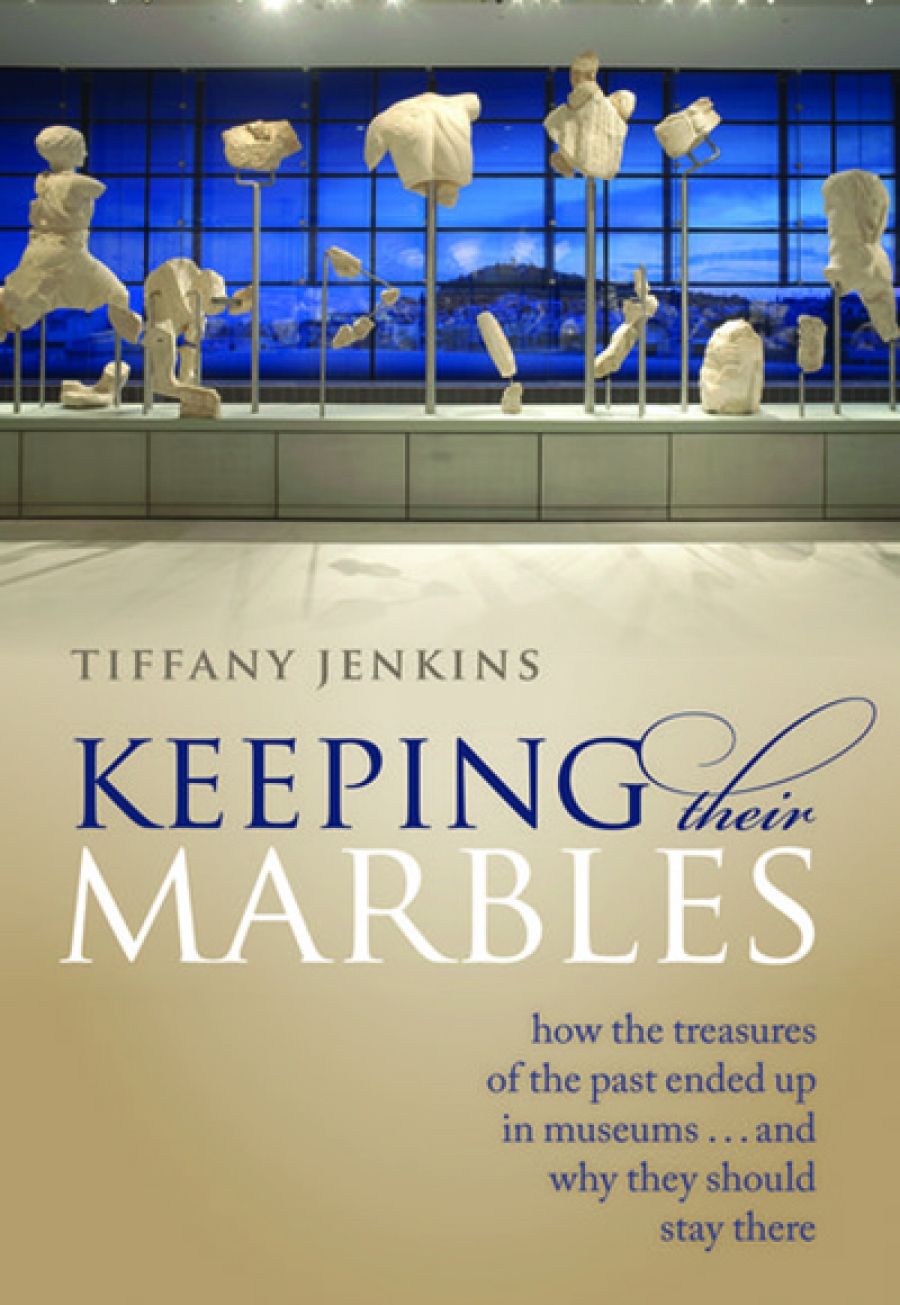

- Custom Article Title: Christopher Allen reviews 'Keeping Their Marbles: How the treasures of the past ended up in museums ... and why they should stay there' by Tiffany Jenkins

- Custom Highlight Text:

There are cases in which it seems, on the face of it, unambiguously right to restore stolen or misappropriated cultural objects to their original setting or at least to their last known address: we can think of the lamentable looting of museums and archaeological sites during the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, and the riots of ...

- Book 1 Title: Keeping Their Marbles

- Book 1 Subtitle: How the treasures of the past ended up in museums ... and why they should stay there

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, $29.95 pb, 383 pp, 9780198817185

Then there are the more difficult cases, in all of which the demand is for the return of objects that were acquired legally in the past, but to which some group or nation now claims a moral right. Some are more questionable than others, like the Turks claiming Greek antiquities as part of their national heritage, when the Turkish peoples were nowhere near Anatolia until many centuries later. The biggest and most vexed case of all is the Greek demand to return the frieze and pedimental sculptures removed from the Parthenon by Lord Elgin with the permission of the then Ottoman government, and housed in the British Museum for just over two centuries.

These are the sorts of questions canvassed in Tiffany Jenkins’s book, which is full of fascinating material, both about the origin of museums and more recent controversies about their vocation in the contemporary world, and the ultimate legitimacy of holding the artefacts of other nations or cultural groups. Some of Jenkins’s historical survey, however, is marred by inaccuracies that undermine the reader’s confidence. Thus the Studiolo of Francesco I is in the Palazzo Vecchio, not the Medici Palace. The characterisation of Sir Joshua Reynolds as Neoclassical, as opposed to Winckelmann as a Romantic, is odd. The destruction of Athens by the second Persian invasion was in, not ‘around’ 480 BCE. Napoleon’s army was not yet known as the Grand Army in 1798. Cuneiform was impressed, not ‘chiselled’, into clay. There are many other things like this, as well as numerous repetitions and some inconsistencies, that could easily have been avoided with a good editor; it is surprising that Oxford University Press could not do better than this.

The most interesting and useful part of the book is in the author’s coverage of recent controversies concerning two related matters: the restitution of cultural materials, and their exhibition in the great universal museums of the world, which happen for historical reasons to be in the principal cities of Europe and America. The works in question were gathered into these museums during the period, from the Industrial Revolution onwards, when Europe surged ahead of the rest of the world in technological development and military power and extended its control over much of the world’s population.

Colonisation, the subject of so much angst today, was historically speaking the first stage in the transfer of the new technology to less developed peoples, whose way of life has been dramatically transformed, for better and for worse, since that period. At the time, almost all peoples, and especially those still at a tribal stage of culture, lived entirely enclosed in their own world of beliefs and practices. The Western mind, which had inherited the dynamism and the spirit of enquiry of the Greeks, was fascinated by the idea of an encyclopedic understanding of nature and of humanity: archaeology, anthropology, and linguistics were fields of study that grew spectacularly in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In the process, archaeological and anthropological material was voraciously collected and served the unprecedented development of historical, prehistorical, and ethnographic knowledge. Some of the means by which artefacts were acquired at the time may now seem questionable, but the great museums into which they were gathered are themselves monuments to a stage in the broader history of humanity. Today, though, they are under constant attack from two sides: nation-states seeking the repatriation of objects; and tribal peoples demanding a say in the way that their cultures are presented.

The first demand raises the question of who ultimately owns monuments of the past, especially when the ethnic groups now dominant in many places (Turks in Anatolia, Arabs in Egypt) have no connection with the ancient populations, and when the civilisation of the Greeks and the Romans has become the common heritage of humanity. In this regard, Jenkins’s conclusion that the Parthenon marbles are probably best left as they are – divided between Athens and London – is slightly anticlimactic but not implausible.

The other set of demands raises all the questions of ‘identity politics’, where minorities of various kinds feel they have a right to determine how, and even whether, cultural artefacts made by their forebears are displayed to a wider public. In effect, they want to reassert their inherently self-centred perspective, resisting the more open and inclusive one which the museum fosters by the juxtaposition of different cultures; in the same way, religious zealots and members of cults resist the study of their beliefs from the point of view of comparative religion.

It clearly makes sense, of course, to engage in a dialogue with any surviving culture that we are sincerely trying to understand. The tendency today, however, widely supported and even initiated by museologists, is simply to give in to tribalism; our sense of universal humanity has been debilitated by decades of relativism and self-doubt promoted by feminism, post-colonialism, and other academic ideologies. But as Jenkins rightly points out, identity politics has flourished in an age when real political questions of class and wealth have been obliterated by the irresistible momentum of globalised economic and technological development. Identity politics allows people to get angry on social media, to indulge in self-pity and resentment, to call themselves activists and even to silence their critics, but these charades have no effect on the forces that determine, and are rapidly changing, the way we all live today.

Comments powered by CComment