- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

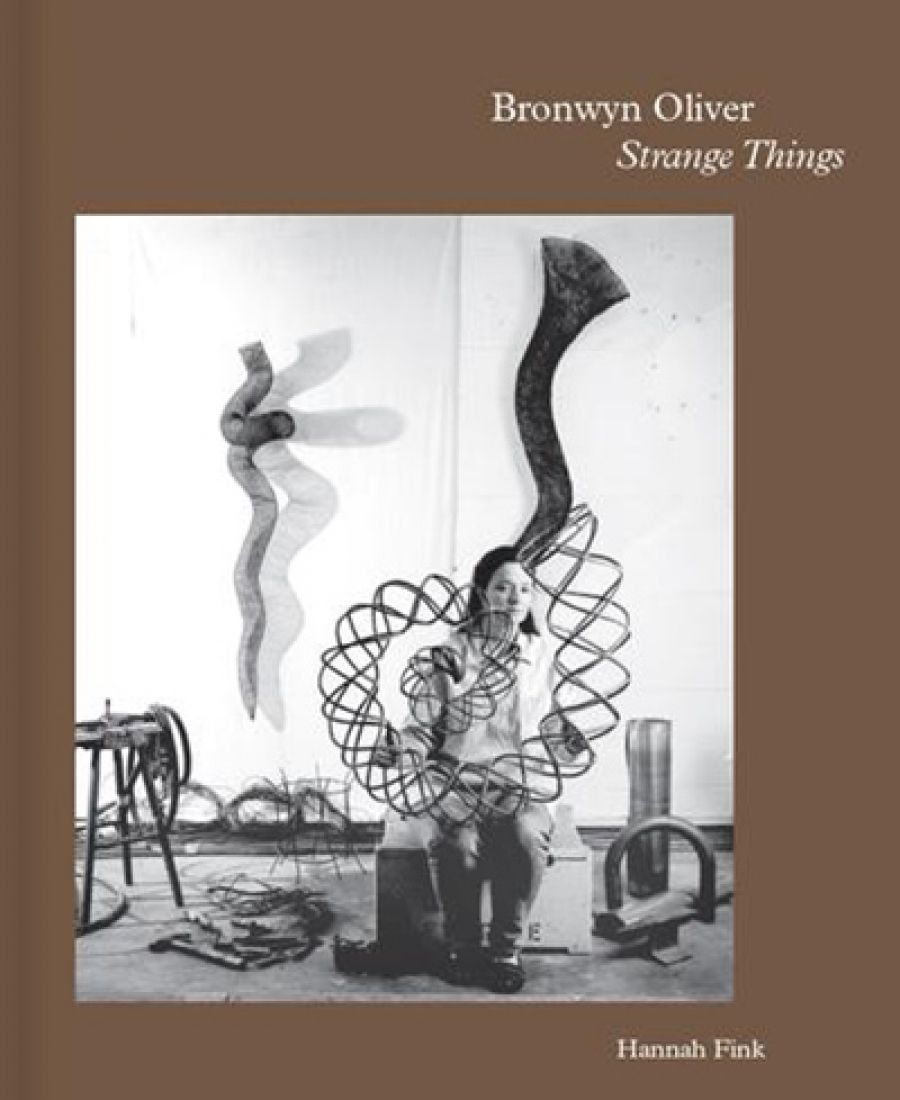

- Custom Article Title: Brigitta Olubas reviews 'Bronwyn Oliver: Strange things' by Hannah Fink

- Custom Highlight Text:

Almost twelve years after her death, Bronwyn Oliver (1959–2006) remains one of Australia’s best-known sculptors; her artistic legacy supported by the prolific outputs of an intense and high-profile studio practice across three decades, by public, private, and corporate commissions, and by a string of prizes, awards, and fellowships ...

- Book 1 Title: Bronwyn Oliver

- Book 1 Subtitle: Strange things

- Book 1 Biblio: Piper Press, $59.95 hb, 240 pp, 9780975190159

Oliver emerges from this first sustained account of her life and work as emphatically an Australian artist, in the sense that the designation might indicate the location of her art practice, rather than any imagined limitation of reference or indeed of achievement. Fink quotes Oliver contemplating her first return to Sydney, after studying at the Chelsea School of Art in London, on the prestigious Travelling Art Scholarship: ‘I’ve always been a stranger … Being in England made me realise that Australia was the place where my foreignness felt most comfortable.’ The book traces the extensive reference points of Oliver’s art; the ways it was subtended by meticulous and inventive research undertaken on or proposed for a series of international fellowships. She notes that Oliver ‘had long wished to visit China, since discovering the ceramics and bronzes in the Musée Cernuschi in Paris’, and that she proposed for the Helen Lemprière Bequest ‘a program of independent travel and study focusing on a cross-cultural comparison of Eastern and Western metalworking techniques during the Bronze Age [and] included an encyclopedic potted history of ancient metalwork, so detailed and comprehensive it seemed already to answer her proposal’. Alongside this scholarly intensity, we read of Oliver’s acute and engaged response to her artist contemporaries, seen compellingly, for instance, in her discussion of Rosalie Gascoigne for Art & Australia in Chapter 7. Such connections with diverse artist worlds continue to inform and complicate the perhaps more immediately apparent local associations that bind Oliver’s sculptures to their sites, setting her work in the context of a wider world.

Fink’s account of Oliver’s development as an artist is grounded in a capacious understanding of the terrain of Australian art in the postwar decades. Particularly engaging is the sense she gives of the making-do ethic of 1960s Inverell as a form of art training: ‘Everyone in Bronwyn’s family made things. Grandma Gooda was always busy crocheting doilies, knitting jumpers, and making “funky stuff, poodle doorstops and beer-bottle covers with pom-pom ears”. She taught the girls how to make crepe paper flowers and how to knit.’

Bronwyn Oliver's sculpture Palm, Sydney Botanical Gardens (Wikimedia Commons)Fink also accords a centrality to the question of art pedagogy that is quite telling, not just for the importance of teaching across Oliver’s own life, but in the ways it informs and inflects more broadly the cultural history of postwar Australia, reminding us of the ways that education transformed Australian society and culture through those decades. There is a resonant arc being drawn between the Saturday morning art classes that the young Oliver attended at Inverell TAFE, taught by Ian Howard, ‘a twenty-two-year-old art school graduate in his first year out for the Department of Education’, and her later position as art teacher at Sydney’s Cranbrook School, with the work of teaching an essential and ongoing dimension of formal art practice across the social spaces delineated by these two locations. Oliver was quite explicit about this; Fink quotes her in a speech made towards the end of her life: ‘In my education classes at college I had been most interested in what drives human beings to make an image. What compels us to make art works? Spending time in a classroom with young children was the perfect place to try and understand this need.’ The account of Howard’s Inverell TAFE art classes is quite inspiring in the ways it focuses on an unfettered and often comedic creativity at once very much of its regional setting and at the same time unconstrained by it. It is a lovely instance of the broader work that the practice and teaching of art can achieve, of, that is to say, their larger value.

Bronwyn Oliver's sculpture Palm, Sydney Botanical Gardens (Wikimedia Commons)Fink also accords a centrality to the question of art pedagogy that is quite telling, not just for the importance of teaching across Oliver’s own life, but in the ways it informs and inflects more broadly the cultural history of postwar Australia, reminding us of the ways that education transformed Australian society and culture through those decades. There is a resonant arc being drawn between the Saturday morning art classes that the young Oliver attended at Inverell TAFE, taught by Ian Howard, ‘a twenty-two-year-old art school graduate in his first year out for the Department of Education’, and her later position as art teacher at Sydney’s Cranbrook School, with the work of teaching an essential and ongoing dimension of formal art practice across the social spaces delineated by these two locations. Oliver was quite explicit about this; Fink quotes her in a speech made towards the end of her life: ‘In my education classes at college I had been most interested in what drives human beings to make an image. What compels us to make art works? Spending time in a classroom with young children was the perfect place to try and understand this need.’ The account of Howard’s Inverell TAFE art classes is quite inspiring in the ways it focuses on an unfettered and often comedic creativity at once very much of its regional setting and at the same time unconstrained by it. It is a lovely instance of the broader work that the practice and teaching of art can achieve, of, that is to say, their larger value.

This is an important book about a great and mysterious artist. Hannah Fink draws on extensive biographical research to present Oliver’s life – the motivations and lacunae, the diverse perspectives and eddying influences – but just as valuable is the depth of her understanding of contemporary visual art, which informs the fine and detailed commentary on the works of art themselves. Fink notes in her final paragraph that it is now ‘time for the life of her sculpture – for new generations to encounter her works, to wonder how they were made, and what they might mean’, a compelling invitation which is made quite real by the work of this book.

Comments powered by CComment