- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Pastiche, not a homage

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

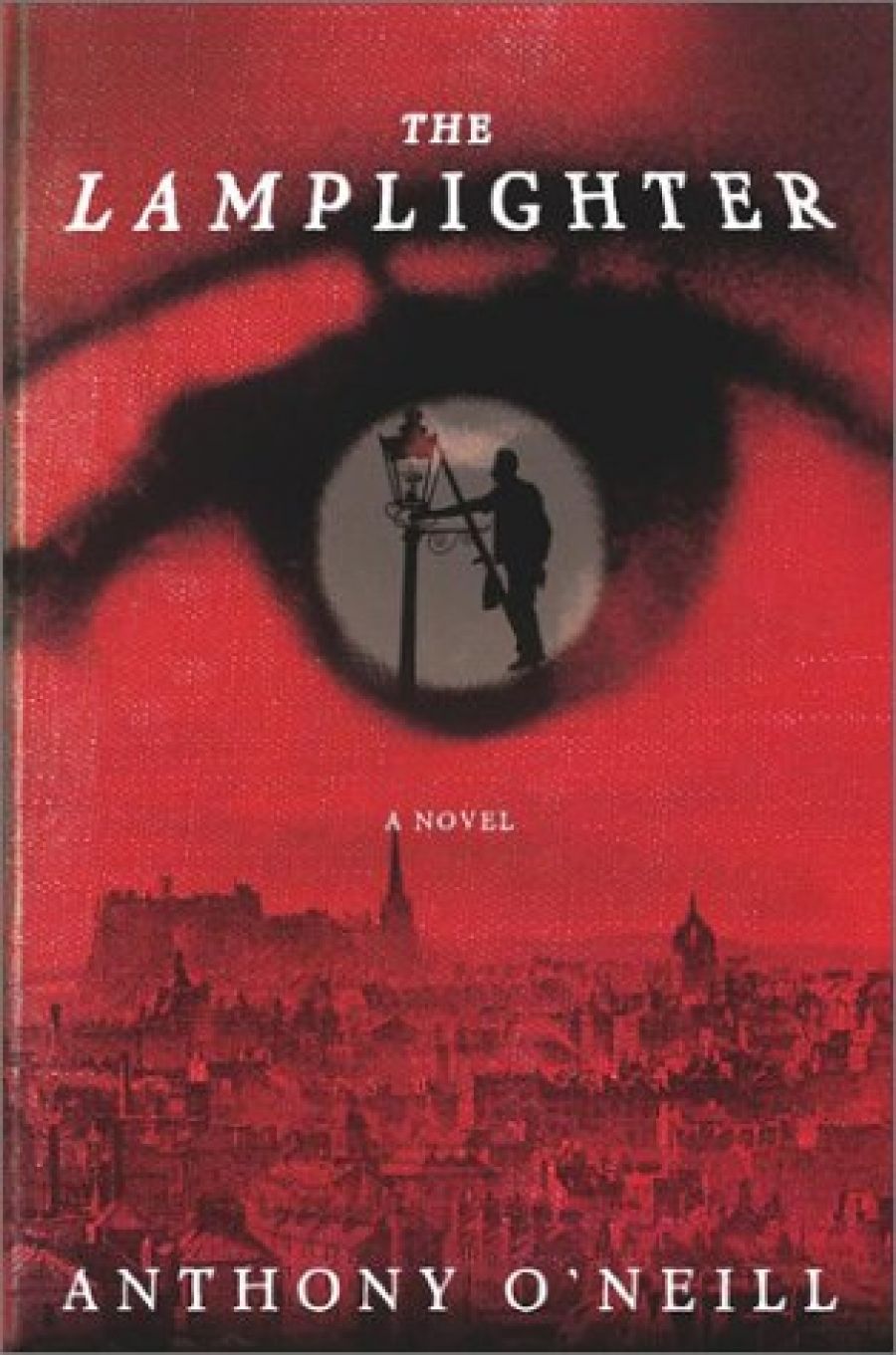

To an appreciable extent, this is a book that can be judged by the cover. In the auto-interview accompanying the publisher’s media release, Anthony O’Neill explains that he was motivated to write his second novel by a desire to ‘emulate certain classic tales of the macabre that emerged from the nineteenth century, arguably the greatest century for novels’. In particular, he states that The Lamplighter is ‘my attempt to write something like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, without it being a homage – I wanted it to live and breathe in its own right’.

- Book 1 Title: The Lamplighter

- Book 1 Biblio: Flamingo, $39.95 hb, 361 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/the-lamplighter-anthony-o-neill/book/9781416575320.html

Naturally, our understanding of the past is bound up with the forms of expression that characterise a particular era. Thus it is difficult not to read the novels of Dickens, say, as some form of social history. Elements of pastiche are found in a novel such as A.S. Byatt’s Possession, which gives a sense of the past on its own imaginative terms. There have also been many attempts to re-create entire nineteenth-century novels in this way. A notable recent example is Michael Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White. Faber’s novel imitates self-consciously the narrative conventions of the Victorian novel, while at the same time querying its anachronistic moral assumptions.

Pastiche of the latter kind has perhaps been raised to its highest art – the self-concealing type – by Charles Palliser’s masterpiece The Quincunx. Palliser, whose very name evokes a bygone literary era, took more than a decade to create a novel that on the surface reads like a novel of its time but is a contemporary novel of truly astonishing depth and complexity.

Palliser has written of his ‘love of Dickens at an early age and my desire to recapture the intensity of that experience’. Similarly, O’Neill has been inspired to write his version of a classic novel by his reading of such as a child: ‘When I was a boy I bought the World’s Classics from the supermarket for fifty cents each and read them avidly: Dickens, Brontë, Verne, Dumas, Bram Stoker.’

The Lamplighter is a densely imagined elaboration in prose of the eponymous short poem by Robert Louis Stevenson, which tells of a child’s vision of Leerie, the nocturnal creature that turns the dark into light. O’Neill’s story is no fairy tale, however. A series of gruesome murders have taken place at night in old Edinburgh, and the police are baffled. It is the kind of Jack the Ripper scenario that would not be out of place in one of Ian Rankin’s Rebus novels or, more appropriately still, given the pastiche factor, the recent television series Dr Bell and Mr Doyle.

Indeed, one of the main characters, Thomas McKnight, a philosophy professor, takes the Dr Bell/Sherlock Holmes amateur sleuth role in the investigation. Joseph Canavan, a somewhat enigmatic Irish cemetery attendant, assists him. The bumbling copper part in the tale is filled by the ageing, seemingly incompetent Carus Groves. The interest of the investigators focuses on a disturbed young woman who claims to have had visions of each of the murders.

The Lamplighter certainly has the look and feel of a nineteenth-century novel, but could it really be read as one? In preparing this review, I reread Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886). What strikes the reader almost immediately is the lack of incidental detail and background explanation compared with O’Neill’s painstaking recreation of the same time and place. The modern reader might take for granted the once novel idea of divided consciousness and the corrosive effects of drugs that Stevenson’s original readers found so new and exciting.

In fact, it is well-nigh impossible to read Stevenson’s original text without already knowing its secret, yet in its time it was first and foremost a thriller. For us now, the atmosphere and the physical space conjured by countless filmed versions of the story are at least as important as the theme, and this effect of cultural memory is reflected in O’Neill’s remote evocation of the city Stevenson knew personally.

Comments powered by CComment