- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The world as it is

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

One of the puzzles of Australia’s diplomatic service is the comparative lack of informative memoirs by senior diplomats. Of the sixteen heads of Foreign Affairs mentioned in this book, only three apart from Richard Woolcott – Alan Watt, Alan Renouf, and Peter Henderson – have written memoirs (although John Burton wrote much about international conflict management, and Stuart Harris – more an academic than a public servant – has written about many international issues, especially economic ones). Some senior figures have contributed columns and articles, but many other senior and respected ambassadors have written nothing. Perhaps this is one reason for the lack of a profound appreciation of international affairs in Australia, which Woolcott so deplores. This book, however, is a substantial contribution to the literature, situated firmly in the realist tradition, and is probably the best memoir to date from a former Australian diplomat.

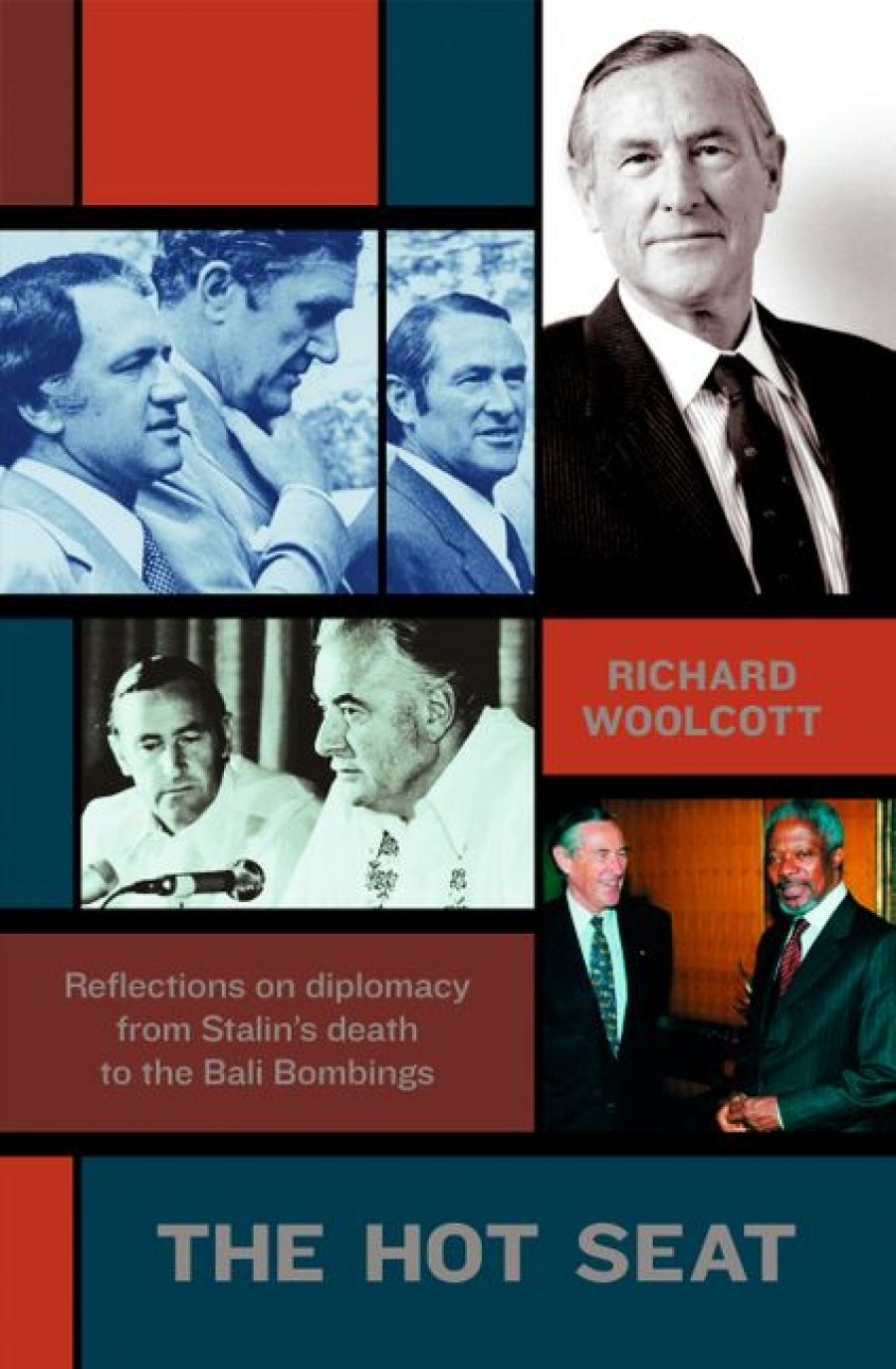

- Book 1 Title: The Hot Seat

- Book 1 Subtitle: Reflections on diplomacy from Stalin’s death to the Bali bombings

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $45 hb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/the-hot-seat-richard-woolcott/book/9780732278809.html

Woolcott can hardly be bound by the East Timor issue. He began as a Russia specialist, and he provides a fascinating account of Moscow at the time of the Petrov defection, the consequent breaking of diplomatic relations, his return for a second Russia posting, and the death of Stalin. We hear of several postings in Africa, including seeing apartheid (which he already detested and argued against) firsthand, and much of black Africa, including – famously – Liberia, where he attended a presidential inauguration and wrote a humorous dispatch about it that infuriated the Foreign Minister (Paul Hasluck) and was subsequently leaked to the press. Later, he became a close adviser to Prime Minister McMahon, and describes several occasions, notably a visit to Washington, when McMahon’s ineptitude made his officials cringe. Then the Whitlam era generated excitement, as new opportunities and issues opened up.

This led to the controversial period when he was ambassador in Indonesia. Woolcott remarks on Australia’s astonishing ignorance of its own neighbourhood: ‘Most Australians knew dangerously little about their large and potentially volatile neighbour.’ Alas, this remains the case. He argues for behaviour adapted to local circumstances:

The first rule in negotiating with most Asian countries in a culturally sensitive manner, especially Indonesia, is not to force the other government into a position where it feels it is obliged to agree with the proposition or reject it.

He devotes chapters to East Timor, the Philippines, the United Nations (where he spent six years), the inception of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) organisation (an amazing feat of intensive diplomacy by Australia), and even Antarctica, where he played in probably the only cricket match ever held there. The chapter on Indonesia includes accounts of unsuccessful efforts to persuade Gough Whitlam and Don Willesee to reach a unified approach on the East Timor issue, a mystified Suharto listening to Woolcott’s account of the Whitlam dismissal (‘Why didn’t Whitlam call out the armed forces?’), and a visit by an obsessed Malcolm Fraser, who pressed the Indonesians too hard for a communiqué formulation on the Soviet presence in the Indian Ocean, which the Indonesians then promptly disowned (illustrating the point about culturally sensitive negotiations).

Woolcott characterises Suharto as friendly, cautious, and thoughtful, not nearly as repressive and corrupt as he was portrayed in the Australian media, but with a tendency to isolate himself and to be reluctant to deal with corruption. It is important in reading this to recall that Woolcott’s posting occurred in the 1970s, when perceptions of the greed of Suharto’s family, though widespread, were limited compared with what happened later. Suharto told Woolcott that impressions of an expansionist Indonesia were misconceived, disowning Sukarno’s adventurist foreign policy (especially Confrontation), but justifying in standard terms the absorption of Irian Jaya (‘completing the state of Indonesia’) and East Timor (‘regrettable but caused by Portugal’s failure and Fretilin’s pro-communist activities’). Suharto claimed that Indonesia was stable and contrasted this with the regular changes in leadership in Australia, leading Woolcott to explain that the strength of Australia’s institutions did not depend on individuals, a lesson Suharto never learnt.

For obvious reasons, the chapter on East Timor – headed by the quotation from Daniele Vare that diplomats must deal with the world ‘as it is and not as it should be’ – will be the most controversial of the book. Woolcott identifies several misconceptions that he claims are widespread in Australia. Always the least believable was the allegation that Australia could have stopped Indonesia from invading East Timor, as if Australia ever had the power to prevent Indonesia from doing something it regarded as essential to its national security. As Woolcott points out, a stronger case can be made for a ‘green light’ from US President Ford and Secretary of State Kissinger, who visited Jakarta shortly before the invasion. More troubling were the allegations that the detailed information about Indonesian plans garnered by the embassy compromised Australia by inhibiting a properly negative reaction to Indonesia’s invasion, and that the embassy was aware of the presence of the ill-fated Australian journalists in the border area at the time but did nothing to save them. Woolcott rebuts both assertions in familiar terms. He denies the latter allegation outright, as he always has, and no hard evidence has ever appeared for it. The circumstances will never be properly resolved until the Indonesians come clean, if they ever do. The former allegation is a matter for judgment; Woolcott’s position is clear, but the ‘armchair critics’, as he describes them, will no doubt remain unconvinced.

Woolcott is grudging about the Howard government’s achievement in East Timor in 1998: ‘It seems to think it has achieved a diplomatic triumph.’ He could surely have been more gracious, but he sounds the important warning that Australia may now have to deal with, and prop up indefinitely, a weak and mendicant East Timor, a prediction that he hopes will prove wrong.

From one perspective, the book can be seen as a sustained critique of the Howard government’s foreign policy. Bit by bit, Woolcott’s severe alienation from current policies emerges, as he laments the decline in Australia’s standing in the UN, which he identified on a brief return to New York in 2000. He criticises the ‘megaphone diplomacy’ style of the 1998 East Timor episode, and discloses some background to Alexander Downer’s imprudent public revelation, for domestic political reasons, of the quickly arranged meetings with Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir just after the Howard government’s election in 1996. Finally, he identifies a sharp downturn in recent years in Australia’s constructive engagement with its own region.

Vignettes of Australian politicians include Menzies the avuncular, Hasluck the ultra-conservative, McMahon the maladroit, and the Hayden–Hawke rivalry. His description of Hasluck’s opposition to the very existence of a press relations section in Foreign Affairs (‘A public servant should not have personal opinions’) confirms Malcolm Booker’s picture some years ago of a rigid immobilism in foreign policy during Hasluck’s reign.

Woolcott is sometimes tempted into hubris (‘the embassy was the best Western embassy in Jakarta at the time’), is evidently vain (the cover consists of photographs of Woolcott with the great and powerful) and a great name-dropper (‘I recall saying to Paul Hasluck in 1967 …’, ‘I said to Peacock …’), but can also be engagingly frank (‘this was an error on my part’, ‘my concerns were misplaced’). He intersperses his accounts of serious diplomatic activities with the anecdotes and bizarre incidents inseparable from diplomatic life, but several anecdotes are surprisingly hackneyed. (There is something familiar about the story of the interpreter who doesn’t bother to translate the visiting dignitary’s joke, merely instructing the audience to laugh.)

The lighter side of the book should not detract from the overall impression of a very thoughtful, comprehensive, and important addition to our understanding of Australia’s diplomacy and its place in the world, and the contribution of a major practitioner over the past forty years. The Hot Seat is also a good read. Those who seek entertainment should turn straight to the hilarious Liberia dispatch.

Comments powered by CComment