- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Pearls of exploitation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Childhood is something we take for granted. We all had one, but our idea of when it ended is quite subjective, depending on the society and culture in which we grew up, our economic and class background, and particular family circumstances. In some societies, the end of childhood is quite clear-cut. Most Aboriginal societies in the past (and some in the present) defined the onset of male adulthood by putting boys through stringent initiation ceremonies. Some girls also went through initiation ceremonies, others ended childhood when they reached what was deemed a marriageable age.

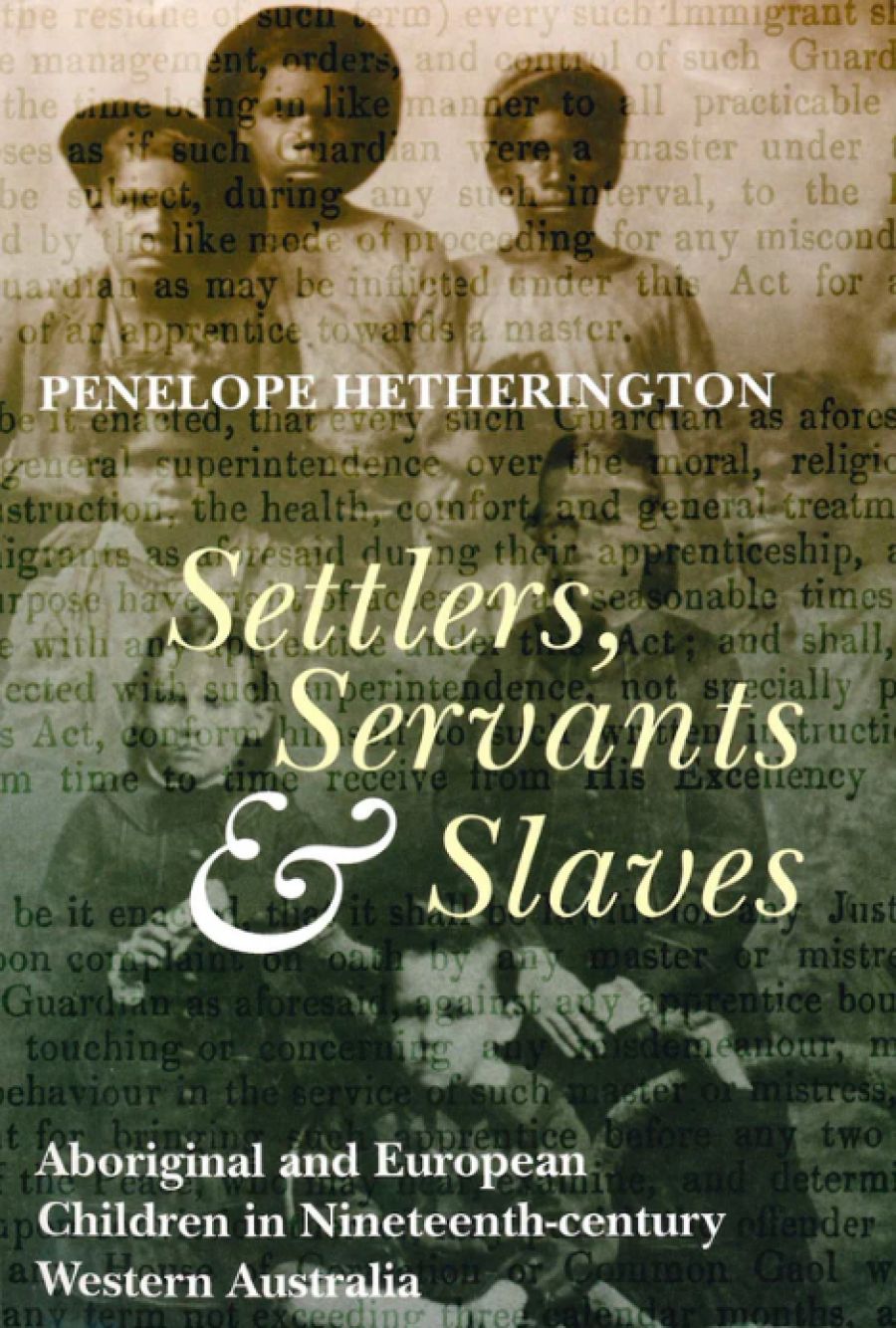

- Book 1 Title: Settlers, Servants & Slaves

- Book 1 Subtitle: Aboriginal and European children in nineteenth-century Western Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Press, $34.95 pb, 246 pp

Western Australian colonial history is presented as the struggle to provide cheap labour for struggling enterprises: farming, pastoralism, and the pearling industry. The colonial population grew very slowly. In 1850, twenty-one years after the establishment of the Swan River colony, there were only 5000 Europeans scattered around what is now the southwest of the state. In that year, as eastern colonies stopped the importation of convict labour, Western Australia welcomed it. But it was not until the gold rushes of the late 1880s and 1890s that the non-Aboriginal population surged and labour shortages in the southwest eased, only to become a problem in the newly colonised pastoral lands to the north. The pearling industry that began along the northern coast in the 1860s remained perennially short of labour as the work was deemed unsuitable for Europeans. Workers had to be imported from Asia, or recruited from the Aboriginal population of the north.

Hetherington does what few other researchers have attempted: she considers both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal history. Unfortunately, she does not try to integrate these two histories. The first half of her book looks at the legislative and institutional treatment of immigrant children; the second considers the treatment of Aboriginal children by the colonial society. I would have appreciated an attempt to compare these régimes. The history of relations between Aborigines and non-Aborigines is generally studied outside the context of attitudes and values of colonial society towards its own working class. As a result of this compartmentalisation of labour history, it is not clear whether the treatment of Aboriginal people reflected the standards and attitudes rife at the time, or whether prevailing racial assumptions ensured that Aborigines had different standards applied to them.

Hetherington’s separate studies of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children do suggest that the victims of child labour (such as the Parkhurst Prison boys, who were imported into the colony) suffered in similar ways to forced Aboriginal child labour. Nevertheless, Aboriginal children and their families could be utilised as labour much more easily than imported labour. Property owners viewed Aboriginal people as potential labour going to waste in the bush. They believed they had the right to pluck young Aborigines from their families and transport them to where their labour was needed. Although Hetherington does not have figures for Aboriginal child labour in the pearling industry, it is evident from the data that many Aboriginal children were forcibly taken from their families to work on the pearling boats in the northwest of the colony. The conditions under which they were taken and put to work were appalling. The few critics who voiced concern over the treatment of these workers did not trust the colonial government and its ministers (such as Attorney-General Septimus Burt) to take action to protect these children, since they represented the employers’ interests.

Settlers, Servants & Slaves shows yet again that the colonial history of our country was not the laudatory story of principled, Christian settlers setting out to plant British law and civilised society on the other side of the world, as Keith Windschuttle, Rod Moran and other recent revisionists would have us believe. Rather, the settlers were trying to make a comfortable and profitable living in adverse circumstances. The only way they believed they could achieve their aims was to access and exploit cheap labour. They did this first by attempting to import a working/peasant class from England. When this did not succeed, they turned to the Aboriginal population, and to orphaned and underprivileged children in their own society. From 1850 to 1868 labour problems in the south of the colony were solved by importing convict labour, but, as the northwest of the colony was opened up for pastoralism and pearling, settlers imported labour from Southeast Asia, China, and Japan, and exploited the region’s Aboriginal population. Young, pliable labour was sought. Hetherington argues that a large portion of that labour force was adolescents and pre-adolescent children.

Comments powered by CComment