- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

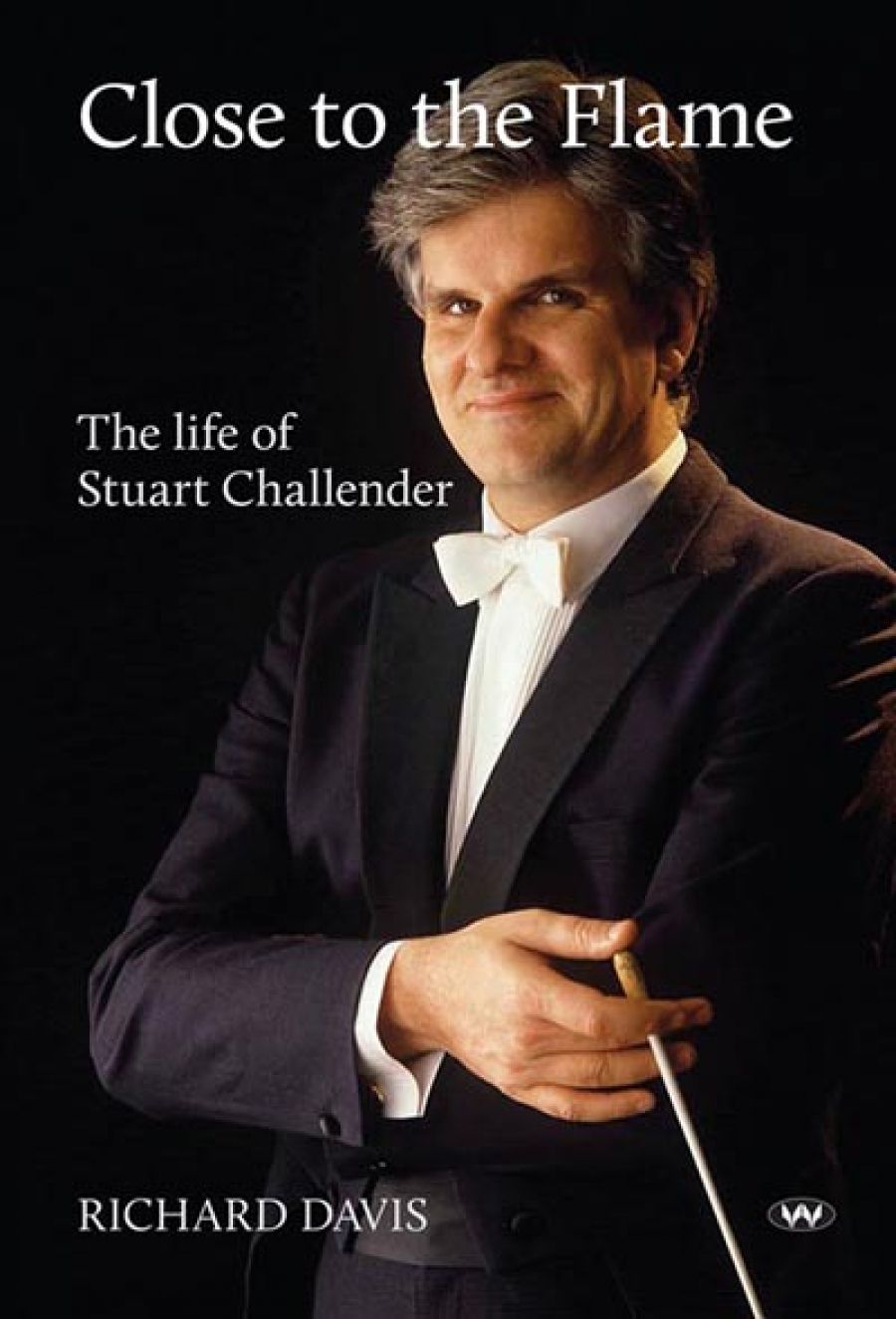

- Custom Article Title: Ian Dickson reviews 'Close to the Flame: The life of Stuart Challender' by Richard Davis

- Custom Highlight Text:

Richard Davis is admirably determined that major Australian musical artists whose careers were attenuated by illness should not fade into oblivion ...

- Book 1 Title: Close to the Flame

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life of Stuart Challender

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $45 hb, 243 pp, 9781743054567

Challender was born in Hobart to parents who were not particularly musical. His father, David, was a successful Australian Rules footballer; his mother, June, a competent pianist. His innate musicality was encouraged by his grandmother, Thelma, somewhat to the dismay of her daughter and son-in-law. Interviewed late in life, she acknowledged her influence, claiming to have recognised his talent while he was still in the cradle and fostering it in spite of his parents’ reservations. ‘Yes, they blamed me,’ she says half-jokingly. It was, however, his father who, in an effort to bond with this cuckoo in the nest, took him to his first orchestral concert. The fourteen-year-old Challender was overwhelmed. ‘I was transported by the music,’ he later said. ‘And of course I was fascinated by the conducting. There and then ... on the spot, I decided that a conductor is what I wanted to be.’

As a boy, Challender had little interest in sport; his father took him to one football match with disastrous results. Challender was considered ‘different’ and consequently became a target for school bullies. Like many gay, artistically inclined teenagers of the period, he retreated into himself and developed deep-seated reserves of reticence and mistrust which remained with him almost until the end of his life.

It is perhaps a great simplification which bears some truth to divide performing artists into two types: those who are naturally larger than life characters and who command attention on and off stage; and those whose natural reserve melts away when they are performing in front of an audience. By all accounts, Challender belonged very much to the second group. To those of us who knew him superficially, he could seem a forbidding presence lightened by occasional flashes of warmth and humour, which were obviously mainly reserved for those closest to him.

It is one thing for a teenager in 1960s Hobart to decide that he wants to be a successful conductor and quite another to achieve that ambition. Davis follows Challender through his undergraduate studies at the Melbourne University Conservatorium to his conducting début with the Victorian Opera Company. Like most Australian artists of his generation, Challender made the obligatory overseas sortie and took the traditional route for a young would-be conductor, working in a variety of European opera houses as a répétiteur and grabbing conducting opportunities as they came along. Impatience with the slowness with which his European career was developing led him to jump at The Australian Opera’s offer of a position as répétiteur and staff conductor.

It was on his return home that Challender finally came into his own. His success with The Australian Opera, plus the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s disastrous choice of the eccentric Czech Zdenĕk Mácal as their transient musical director, led to his being offered that position in 1987, just as he was coming to terms with the fact that he was HIV positive. It is not too dramatic to assert that the most important part of his career was shadowed by death.

As the HIV developed into AIDS and Challender became weaker, his condition became more obvious and this most private of men was forced to come out both as a gay man and as one living with AIDS. Fearing the worst, he was amazed at the overwhelmingly supportive response of the public and allowed his friend David Marr to make a documentary about him. The Big Finish, which aired as part of the ABC’s Four Corners program in August 1991, is still an extraordinarily moving experience.

Davis mentions many of the performances conducted by Challender which this reviewer was lucky enough to attend. His rapport with the Romanian soprano Nelly Miricioiu, keeping the sometimes intemperate singer under control while giving her the emotional freedom she needed, gave us an indelible Violetta in La Traviata, and Moffatt Oxenbould, at the time the artistic director of The Australian Opera, is right to single out Challender’s conducting of Jenufa as a company highlight. Who will forget the mighty Leonie Rysanek intoning ‘Ze icy hend of dess faucing its vaay een’? It was an icy hand that was already reaching out for Challender.

Stuart Challender with Joan Sutherland after a performance of Lucia di Lammermoor in Rotterdam, 1982 (Stuart Challender Papers)

Stuart Challender with Joan Sutherland after a performance of Lucia di Lammermoor in Rotterdam, 1982 (Stuart Challender Papers)

Davis also rightly highlights Challender’s championing of Australian composers. Carl Vine, for one, generously acknowledges the support and advice he received from him. Challender was a major component of the extraordinarily talented group that brought Patrick White’s Voss to the opera stage (he conducted the world première in Adelaide in March 1986).

But there are two occasions that were especially memorable for this reviewer. The first was one of the two now legendary performances of Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony which Challender conducted with almost reckless intensity to shattering effect at Sydney Town Hall in 1987. The second, an altogether more harrowing experience, was the opening night of a new production of Der Rosenkavalier on 2 September 1991, presented by The Australian Opera in what was then the Opera Theatre (now and forever to be known by readers of the Sun-Herald as the Joan Sullivan Theatre). The Big Finish had just aired and the entire audience was aware that this was in all likelihood the last time they would see Challender perform. Challender entered to an almost hysterical ovation and the opening bars of the prelude were most uncharacteristically inaccurate, caused apparently because the conductor could not see the score through his tears. He soon had everything under control, but the intensity of the occasion made moments of an opera concerned with the passing of time and the impermanence of all things almost unbearable.

As with Wotan’s Daughter, Davis has included a comprehensive discography. His well-researched and readable book is an admirable record of an artist whose legacy is strong despite the shortness of his career.

Comments powered by CComment