- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

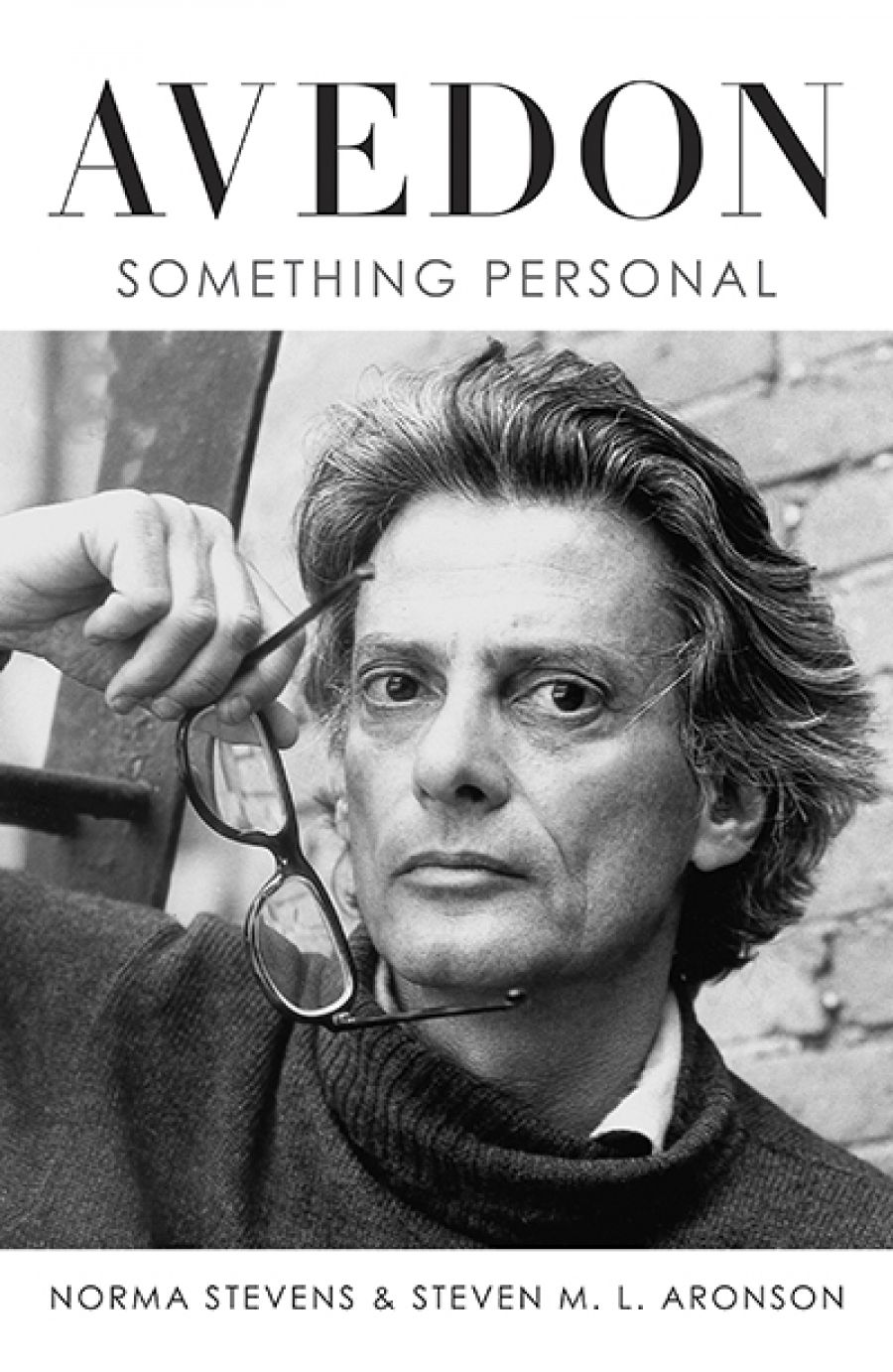

- Custom Article Title: Kevin Rabalais reviews 'Avedon: Something Personal' by Norma Stevens and Steven M.L. Aronson

- Custom Highlight Text:

Richard Avedon never considered himself a photographer, much less (the horror!) a fashion photographer, yet in sixty years of peripatetic productivity (1944–2004) he revolutionised that field and reinvented photographic portraiture. His work in the fashion industry – as a photographer and, often, creative director of advertising ...

- Book 1 Title: Avedon

- Book 1 Subtitle: Something Personal

- Book 1 Biblio: William Heinemann, $65 hb, 720 pp, 9781785151835

‘There is no truth, no history – there is only the way in which the story is told,’ Avedon said. It is no surprise, then, that Avedon offers many books in one: straightforward biography; remembrance of Avedon’s working life by Stevens, the photographer’s long-time studio director and business manager; and an oral history of the Avedon studio. Those who speak in these latter sections, interspersed throughout, include Mikhail Baryshnikov, Veruschka, Twyla Tharp, Claude Picasso, John Lahr, and Mike Nichols, with whom Avedon, twice married himself, had a long love affair. The latter detail, one of the many personal revelations about a man famous for his secrecy, placed Avedon in the gossip pages before the book’s publication. The Richard Avedon Foundation has disavowed the credibility of some of Stevens’s claims and has called for the publisher to withdraw the title.

Part of the slipperiness of truth here stems, in part if not wholly, from the sensibility of its subject. ‘Dick would sometimes make merry with the facts – he even joked that if he ever wrote an autobiography he would call it Here Lies Richard Avedon,’ Stevens writes. What becomes clear throughout this unconventional biography is that Avedon carried his own climate into every room he entered. ‘It wasn’t that he put you at your ease or in any way made you feel that life was easy, but he did make you feel that life was worth living, every second of it, no matter what was going on,’ recalls Deborah Eisenberg. Avedon’s life became his work. He chose a range of subjects – celebrities and models, yes, but also coal miners, unheralded faces of the American West, writers, politicians and radicals, dancers and artists, inmates of mental institutions, the Vietnam War – to try to comprehend his epoch. Avedon then projected it back to us in ways that make his work and the times inseparable. Spend a few minutes with the Avedon catalogue and you will glimpse what it meant to live in the second half of the twentieth century. As David Remnick recalls, ‘I mean, if you were alive and had your eyes open at a certain extended time in history, you knew his stuff the way you knew the music.’

To say that Avedon changed the game by introducing movement to fashion photography only scratches the surface of his achievement. Some photographers obsess over equipment, others over people. ‘[H]e showed me how it wasn’t just the way you looked,’ recalls Christy Turlington, ‘it was also the energy you created.’ His success depended on that energy. He envisioned what he wanted in advance, often keeping his sittings brief. To elicit a reaction from Ezra Pound after his release from St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, Avedon said, ‘I think you should know that I am a Jew.’

Avedon resented having to put aside his personal work to resume never-ending professional responsibilities, but the price for an Avedon, he believed, was never too high. ‘It’s not God who created our civilization,’ he said, ‘it’s money.’ Avedon brought the same professionalism to his commercial work as he did to his portraiture. Having Avedon photograph you became a sign of ultimate recognition. Isabella Rossellini recalls that, ‘[G]oing to his studio was a bit like going to Michelangelo.’ For Baryshnikov: ‘his single-image portrait of Stravinsky is, for me, the equivalent of an in-depth biography’.

Domiva with Elephants, 1955, Richard Avedon (Flickr)

Domiva with Elephants, 1955, Richard Avedon (Flickr)

Born in New York in 1923 to a Russian-born Jewish father and American mother whose family owned a successful dress-manufacturing business, Avedon – delicate, artsy rather than athletic – sought early self-invention. He had nose surgery in high school. ‘I mean, imagine what my chances would have been if I had turned up at the Bazaar with the nose I was born with,’ he said. Without finishing high school, he found work in a darkroom before enlisting in the Merchant Marine, where he photographed enlisted men for their military ID cards. ‘Every photography critic worth his byline has pointed out that this minimal format – sitter head-on against stark-white background – became Richard Avedon’s template: his trademark portrait style,’ writes Stevens. From there, after studying photography at The New School, Avedon found himself on assignment in Paris.

The same man who posed models on roller skates along the Champs-Élysées shortly after the end of World War II and in Paris’s Cirque D’Hiver (Dovima with Elephants, 1955) still held us in his thrall half a century later. ‘There are teenagers in this city who would kill for a taste of the hectic hipness that Avedon maintains as he nears his eightieth year,’ wrote Anthony Lane in The New Yorker in 2003. Stevens, clearly in her subject’s thrall, boasts of Avedon’s successes, pushing the book, at times, toward hagiography, but it never descends into salaciousness. Instead, Avedon segues smoothly among its sections, making this hybrid structure seem like the only way to tell this story about a complex man and artist. The collage of sections appears before the reader like contact sheets from a lifetime of work. And that work continually articulates Avedon’s intense observations of life in the second half of the twentieth century.

Comments powered by CComment