- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Custom Article Title: Helen Ennis reviews 'Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife' by Pamela Bannos

- Custom Highlight Text:

Vivian Maier has received the kind of attention most photographers and artists can only dream of – multiple monographs, documentary films, commercial gallery representation, extraordinary public interest, and now a biography. However, all this activity and acclaim has occurred posthumously. In her lifetime ...

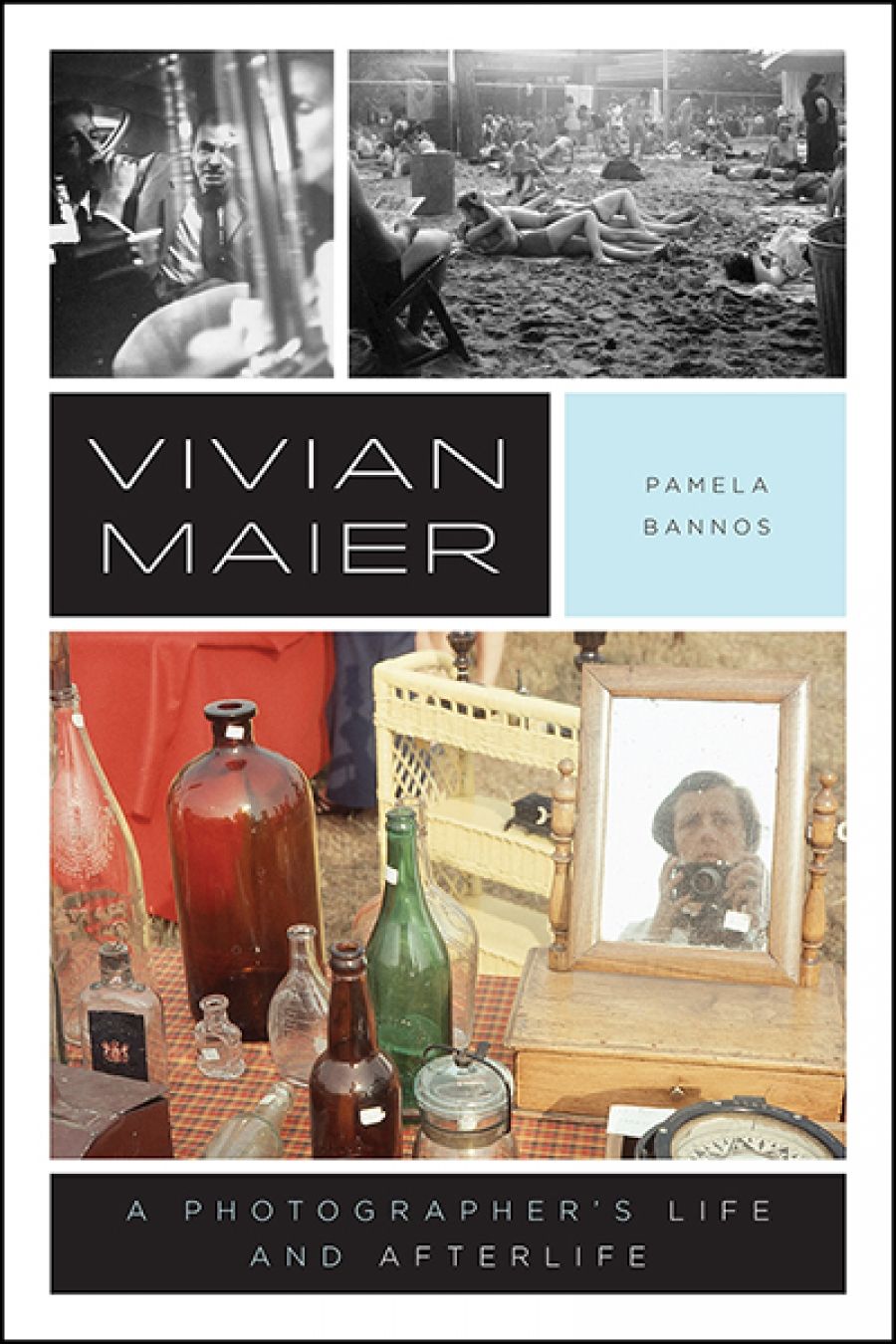

- Book 1 Title: Vivian Maier

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Chicago Press (Footprint), $69.99 hb, 362 pp, 9780226470757

The author of Maier’s biography, Pamela Bannos, is professor of photography at Northwestern University in the United States. Her aim has been to temper the sensationalism around Maier’s life and work. Thanks to her research, we now have a detailed, verified account of the life of a woman variously described as ‘masculine looking’, ‘very big’, and someone ‘who took no shit’. Elucidating the so-called ‘Vivian Maier phenomenon’ and attempting to assess the significance of her legacy was no easy task for Bannos, because the archive has been dispersed and is mostly held by collectors with vested interests. The financial stakes have risen to such an extent that one prospective buyer brought along two armed off-duty law enforcement officers to ensure that his deal with another collector went through (it did, without incident).

Bannos’s book has a dual narrative structure in which a chronological account of Maier’s life and work is interspersed with the contemporary story of her discovery, her ‘afterlife’. Maier was born in New York City in 1926 and took up photography in 1950, with the great bulk of her work being shot on the streets in New York and Chicago. She was estranged from her family for decades, had few if any friends, and supported herself by working as a live-in nanny for middle-class families. She was a rapacious hoarder. One family had to brace the ceiling underneath her bedroom because the weight of her stuff caused it to sag and another client dispensed with her services because the huge piles of newspapers she hoarded represented a fire hazard.

From Bannos’s point of view, Maier is an outstanding photographer whose work warrants incorporation into the canon of street photography. She argues for Maier’s technical and formal experimentation and development, her original style and readily identifiable thematic preoccupations. She discusses numerous photographs in detail, but because so few are included in the book it is not possible to test her views alongside the reproductions. The cursory selection also means the reader must go elsewhere, online or to other publications, to engage with a fuller range of Maier’s photography. This introduces another kind of skewing that arises not only from the operation of different individuals’ tastes but also from the high quality of printing that has been lavished on Maier’s work in order to stimulate the commercial market and attract collectors. Maier herself made only rudimentary prints in temporary darkrooms rigged up in her employers’ bathrooms, and, in her latter years, did not even develop the innumerable rolls of films she had exposed.

There can be no doubting Maier’s commitment to photography. She purchased professional cameras, and her photographic activity consumed her meagre income. As Bannos stresses, she was ‘an incessant picture taker’ who went everywhere with her camera. But what did photography mean to her? And what relevance does her photography have to the field of photography, encompassing both histories of photography and the contemporary scene? These are crucial questions which Bannos does not adequately address. As a biographer, she was faced with the dilemma of a subject who left little trace of her motivations and the workings of her inner life. But the photographs, it could be argued, constitute a form of evidence and Bannos could have gone further in her reading of them. Many observations are superficial and beg for more elaboration. She tells us, for example, that Maier’s interest was ‘excited’ by women in hats, but does not attempt to explain why this might have been the case – or why photographing cemeteries, and mothers with children, were other enduring preoccupations. Nor does she chronicle any significant changes in representations of these subjects over time. Bannos is a respectful biographer but there was scope to deepen her visual analyses regarding Maier’s position as the eternal outsider.

Image from the Ron Slattery negative collection. (Courtesy of the Estate of Vivian Maier © 2017 The Estate of Vivian Maier. All rights reserved.)

Image from the Ron Slattery negative collection. (Courtesy of the Estate of Vivian Maier © 2017 The Estate of Vivian Maier. All rights reserved.)

So far as photography’s history goes, Bannos provides a brief account of major developments in contemporary American photography – especially those sanctioned by MoMA in New York – to give context and reference points for Maier’s work. This is of questionable value, because there is nothing to suggest that Maier was consuming art photography and responding to it, or interacting with other photographers. Rather, everything indicates that she was simply doing her own thing. This is where her practice differs fundamentally from other women photographers like Gerda Taro and Claude Cahun, whose work has also been rescued from oblivion. Their efforts represented a conscious address to the traditions and practices of art and photography, whereas Maier’s appear to relate more to amateur photography and outsider art.

Maier was hospitalised in 2008 and died a few months later as the flurry of excitement around her was gathering pace. Bannos’s narration of the subsequent dissemination of her work through the internet and the operations of a greedy art photography market are among her most useful achievements.

British writer Geoff Dyer has referred to Maier’s situation as ‘an extreme instance of posthumous discovery’. It is yet to be seen whether, as a result of the efforts of Bannos and others, Maier has any impact on photographic practice in the future. As Bannos aptly concludes her biography, ‘Vivian Maier’s story continues on without her.’

Comments powered by CComment