- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: Desley Deacon reviews 'The Best Film I Never Made: And other stories about a life in the arts' by Bruce Beresford

- Custom Highlight Text:

Reading Bruce Beresford is enough to make any aspiring filmmaker think twice about following in his footsteps. ‘The Best Film I Never Made’, the title article of this collection of Beresford’s occasional writing over the last fifteen years, says it all. This is the sad, but in its way hilarious, story of his attempt to put together a ...

- Book 1 Title: The Best Film I Never Made

- Book 1 Subtitle: And other stories about a life in the arts

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 pb, 281 pp, 9781925603101

This is not a new story from Beresford, one of our most successful movie directors. His Josh Hartnett Definitely Wants To Do This ... True stories from a life in the screen trade (2007), and the collection put together by producer Sue Millikin, There’s A Fax From Bruce (2016), introduced us to the excruciating process of putting a project together – corralling finance, star, writer, and director in the one place at the one time long enough to actually make a movie. The Best Film I Never Made gives us several more examples of this less glamorous side of movie making: ‘The Hubert Opperman Saga’ recounts his ten-year involvement with a fantasist who dreamed of making a movie about the Australian champion cyclist. In ‘A Career of Sorts’, looking back on a career that took him from The Adventures of Barry McKenzie in 1972 through Tender Mercies (1983), Driving Miss Daisy (1989), and the thirty-odd others he has directed, he muses on the complexities introduced for the director since about 2000 by digital filmmaking. Not the least of these is setting up the finance. ‘Financing Movies’ goes into more detail about what Beresford calls ‘development hell’. But the reader gets the idea that Beresford finds all this skating on thin ice rather exhilarating. And he believes in his art: ‘Despite all these difficulties,’ he writes, ‘many fine films are made all over the world; there are great directors in every country, dedicated to their art and imbued with the spirit that conquers every obstacle.’

The drama and wonder of Beresford’s career is thrown into vivid relief by the accounts he gives of his background in ‘Family Tree’, ‘My Parents’, ‘Out of Toongabbie’, ‘The End of the Roxy’, and ‘Stumbling towards Directing’. Born in 1940, he grew up in ‘perhaps the most boring decade in Australia’s history’. The family lived in a fibro Housing Commission house in Toongabbie in Sydney’s west. His ineffectual and chronically depressed father and more businesslike mother ran a small electrical goods store. To the young Beresford they appeared to have no interests, and his mother considered that only servants went to the movies. From an early age, however, he was attracted to the offerings at the Parramatta Roxy, Astra, and Civic, and at the age of twelve he had his favourite directors. When he saw John Ford’s The Sun Shines Bright in 1953, he decided he wanted to be one himself.

This was a generation that were able to invent themselves, thanks to postwar prosperity and the opening up of the universities. Beresford’s contemporaries at the University of Sydney included Clive James, John Bell, Les Murray, Germaine Greer, and Robert Hughes. Like many of these, he furthered his education by heading for London; but his future was made in 1970s Australia, where, with $250,000 from the newly minted Australian Film Commission, he began his career as a director with Barry Humphries’ The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972). What he calls ‘critical credibility’ came with David Williamson’s Don’s Party in 1976. The Getting of Wisdom (1978), Breaker Morant (1980), The Club (1980), and Puberty Blues (1981) followed. By 1980 he was being headhunted by Hollywood.

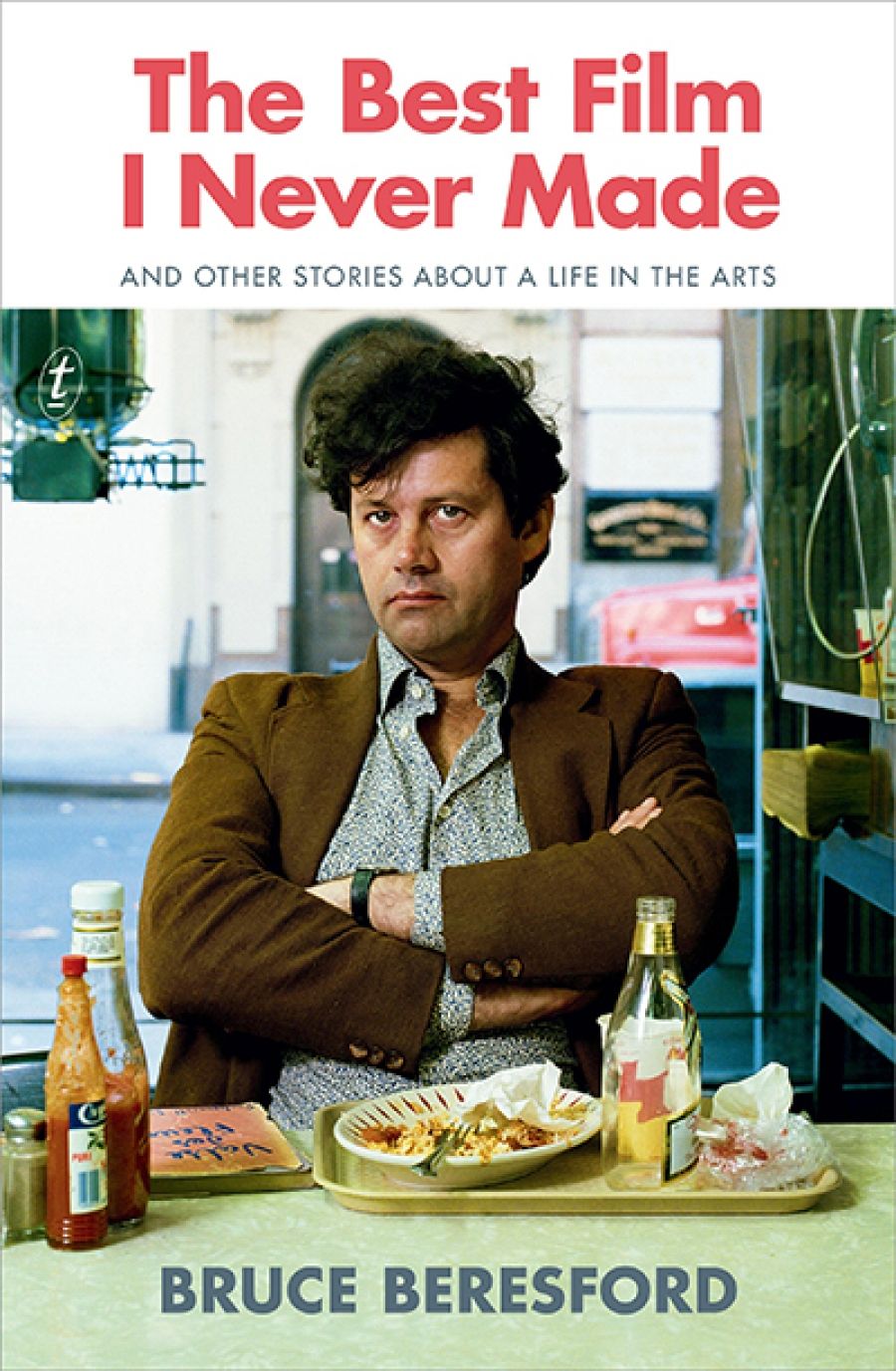

Bruce Beresford directing Puberty Blues, 1981 (photograph by Robert McFarlane, courtesy of National Library of Australia)

Bruce Beresford directing Puberty Blues, 1981 (photograph by Robert McFarlane, courtesy of National Library of Australia)

The most interesting pieces in this eclectic collection are those where Beresford writes drolly about the absurdities of the craft that he loves. He also includes memoirs of writers, directors, producers, composers, and cameramen he worked with. ‘The Two Barrys’ gives an affectionate portrait of Barry Humphries (the other Barry is Barry Crocker). ‘Don McAlpine, Cameraman’ tells how he found possibly the best cameraman Australia has produced in the Commonwealth Film Unit and persuaded him to film The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (in London’s grey gloom). ‘A Brief Guide to American Opera’ (which is actually twelve pages long) reminds us of Beresford’s second, late career as opera director; and articles on Jeffrey Smart and Clive James demonstrate the wide range of arts embraced by this son of Toongabbie.

This is a book that was probably put together for the Christmas market. The quality of the paper is poor, and there is little help for the more serious reader: we are not told where the articles were originally published; there is no index; and the cover photo is identified only in the copyright information. It will make a good present for anyone interested in making movies and in movie history and gossip. Let’s hope that before long Beresford will take time out from the exciting work of putting deals together to write a full account of his extraordinary career.

Comments powered by CComment