- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cricket

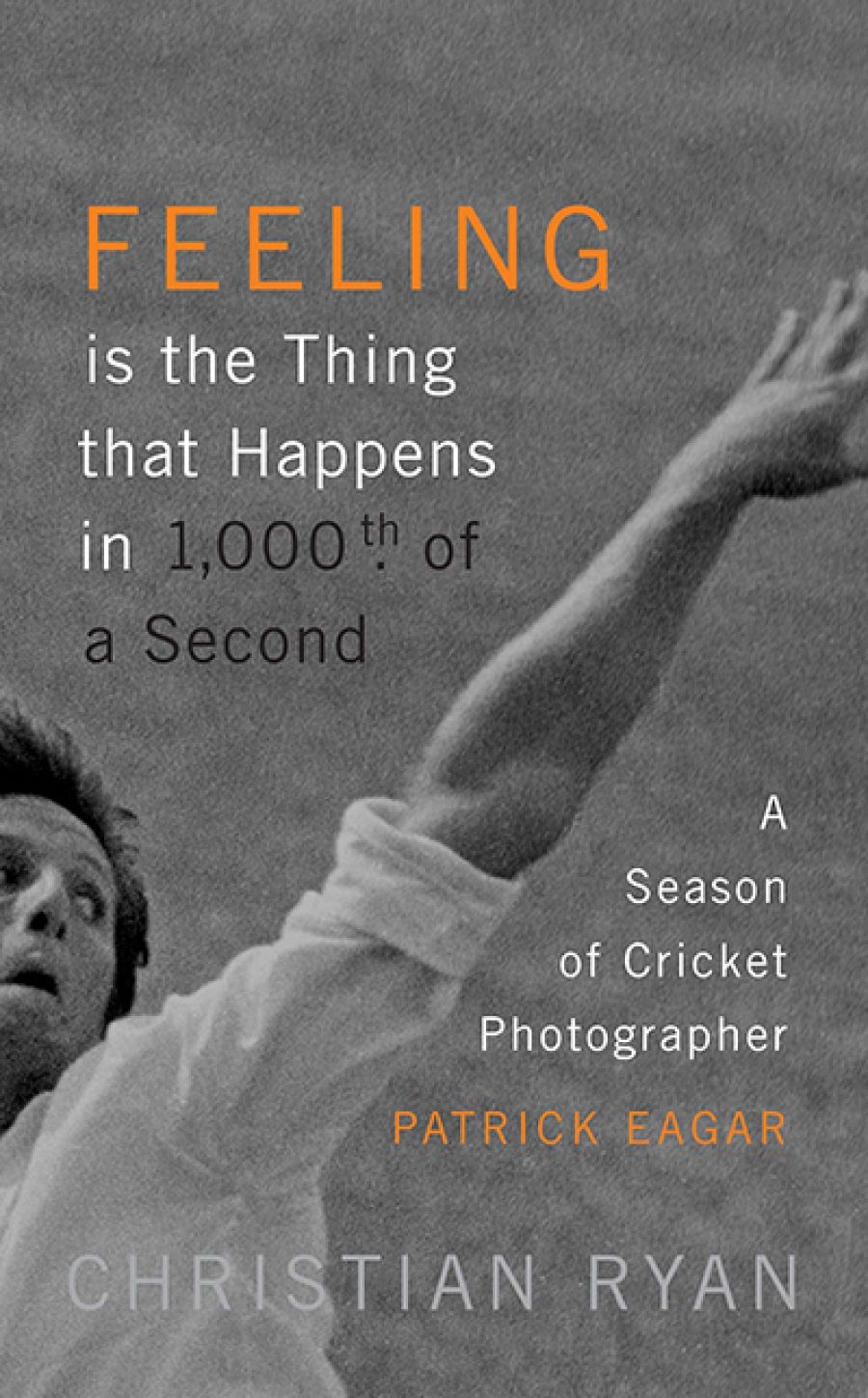

- Custom Article Title: Bernard Whimpress reviews 'Feeling is the Thing that Happens in 1000th of a Second: A season of cricket photographer Patrick Eagar' by Christian Ryan and 'Lillee & Thommo: The deadly pair’s reign of terror' by Ian Brayshaw

- Custom Highlight Text:

A modern cricket photographer using digital single-lens reflex cameras and high-speed motor drives can take 5,000 photos in a day’s play. With such a surfeit of images, the quality of seeing is diminished. For most of his career from the 1970s to the 2010s, English photographer Patrick Eagar would shoot four or five rolls of film ...

- Book 1 Title: Feeling is the Thing that Happens in 1000th of a Second

- Book 1 Subtitle: A season of cricket photographer Patrick Eagar

- Book 1 Biblio: Riverrun, $35 hb, 248 pp, 9781786486820

- Book 2 Title: Lillee & Thommo

- Book 2 Subtitle: The deadly pair’s reign of terror

- Book 2 Biblio: Hardie Grant, $29.99 pb, 272 pp, 9781743792599

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Online_2018/January-February_2018/Lillee%20and%20Thommo.jpg

This all sounds very technical, but in Christian Ryan’s hands it is fascinating stuff and invites a discussion of the changing nature of cricket photography. Who or what prompts memory? Is it David Gower for executing an exquisite cover drive or Patrick Eagar for capturing a permanent record of the stroke?

My knowledge of French literary theory is almost zero. However, because Ryan cites Roland Barthes at a couple of points, I am left wondering whether Feeling Is the Thing That Happens in 1000th of a Second is the first structuralist (or post-structuralist) cricket book. What follows are multiple readings and interpretations of images.

Ryan is an exceptional writer. His biography of Kim Hughes, Golden Boy (2009), peeled back many layers of Hughes’s character and career and was a deserving winner of the British Cricket Book of the Year award in 2010. In 2011 he edited the magnificent Australia: Story of a cricket country, which combined both fine writing and superb photography.

Feeling reveals Ryan’s own feeling for his subject – not merely the work of Patrick Eagar in the 1975 English season; not merely a loose biography of Eagar and comparisons with the work of contemporary American photographers from Sports Illustrated ; not merely a historic appreciation of sports photography world-wide; but of the wider potential of the medium, with references to luminaries such as Robert Capa, Dorothea Lange, Richard Avedon, Garry Winogrand, and Annie Leibovitz.

The book begins essentially with the classic side-on shot of Jeff Thomson poised in the moment of delivery at Lord’s on 1 June 1975, an image ‘showing what sports photography – live, unstaged, not cooked up between a photographer, and performer – could do, be ... In this instance, soft sunshine illuminates Thomson’s action at the moment of maximum exertion with the face a thrilling accident, sinewy, bony, grotesque.’ ‘Thrilling accident’ is a key to this description, because it is an integral part of any great photograph. Eagar has planned this shot, put himself (and his equipment) in the right place at the right time, and the light is kind. Intention is evident, but accidents are essential to the magic. In an absorbing dialogue between author and main subject, Ryan inclines more to intention and Eagar (modestly) to luck and chance.

Intention led Ryan to Eagar. Feeling offers numerous interesting diversions and one of the most rewarding involved the relationship between cricket’s leading photographer and some of its greatest writers. Eagar, who met Neville Cardus twice, describes him as having no interest in photography. By contrast, E.W. Swanton saw Eagar’s merit and published his early pictures in the Cricketer magazine; Alan Ross and John Arlott (both poets as well) collaborated on notable books with him; and he often tried to match his pictures to the words of The Times journalist John Woodcock in capturing the spirit of a day’s play. As Arlott once noted, Eagar ‘renders cricket such a service as no one else in his field has ever done before’.

At the end of his book, Ryan lists some of his influences: two books by Lawrence Weschler, Barthes’s Camera Lucida (1980), Geoff Dyer’s The Ongoing Moment (2005) and Gideon Haigh’s Stroke of Genius (2016) among them. To borrow a phrase from John Berger, Ryan has rendered us a new way of seeing cricket photography.

Lillee & Thommo by veteran writer and former journalist Ian Brayshaw, a long-time Western Australian teammate of Dennis Lillee, details one of the most frightening opening attacks in the history of world cricket. It brings back memories of Thomson’s express pace and lift from good length deliveries – in his words, ‘I just shuffle in ... and go WHANG’ – and Lillee’s measured rebuilding of his grand career after severe back injuries.

A statue of Dennis Lillee at the Melbourne Cricket Ground (photograph by Chris Brown, Wikimedia Commons)A joint biography is a worthwhile project, but the story has a misleading subtitle. The deadly pair’s reign of terror was surprisingly brief, comprising fifteen and a bit Test matches in two years until Thomson’s collision with Alan Turner at Adelaide Oval on Christmas Eve, 1976. Thereafter they played just ten more Tests together before Lillee’s retirement in 1984.

A statue of Dennis Lillee at the Melbourne Cricket Ground (photograph by Chris Brown, Wikimedia Commons)A joint biography is a worthwhile project, but the story has a misleading subtitle. The deadly pair’s reign of terror was surprisingly brief, comprising fifteen and a bit Test matches in two years until Thomson’s collision with Alan Turner at Adelaide Oval on Christmas Eve, 1976. Thereafter they played just ten more Tests together before Lillee’s retirement in 1984.

Brayshaw has interviewed widely, both Australian and international players, and their testimony enriches his text. Not all sources are equal, of course, but one gem comes from Jeremy Cowdrey telling of his father, Colin, having ‘100 per cent confidence in his technique’ when setting off, aged forty-one, to join England’s beleaguered team in the 1974–75 Ashes series. By contrast Dennis Amiss spoke of his own difficulty staying leg side of the rearing ball, whereas Tony Greig and Alan Knott had some success with that method.

Jeff Thomson provides an obvious link between Lillee & Thommo and Feeling. Brayshaw’s description of him offers a lovely complement to Patrick Eagar’s famous photograph:

at the end of a tippy-toe creep in from a relatively short approach, he crossed his feet over in the load-up – a move described as balletic. A virtual pirouette ... The secret to Thomson’s pace was his method of taking the ball back behind his buttocks and then hauling it through with a supremely muscular heave ...

Each of these distinctive books has much to offer their respective readers.

Comments powered by CComment