- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: John Rickard reviews 'Collecting for the Nation: The Australiana Fund' edited by Jennifer Sanders

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1976, when Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser and his wife, Tamie, were on an official visit to the White House in Washington, she was shown the collection of Americana acquired through the White House Historical Association, an idea of Jacqueline Kennedy’s as First Lady. Her enthusiasm for a similar Australian fund ...

- Book 1 Title: Collecting for the Nation

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Australiana Fund

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $79.99 hb, 313 pp, 9781742235698

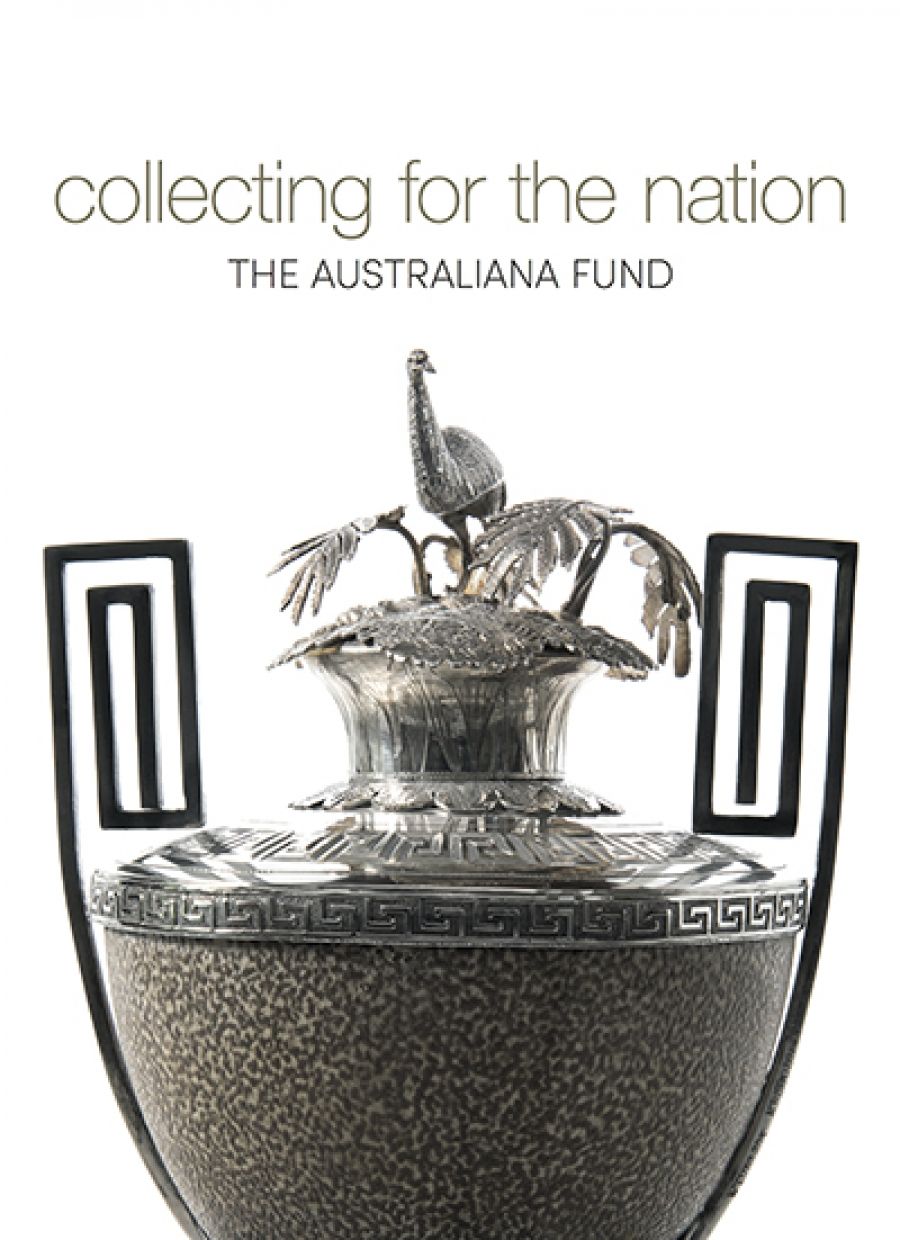

Collecting for the Nation, a substantial tome weighing in at almost two kilograms, is presented as ‘a beautiful illustrated telling of Australian history and culture through the artworks’ in the Fund’s collection. It is divided into two sections, the first recounting the history of the four houses and estates themselves, the second exploring the collection and locating these ‘artworks’ in their historical context.

The four official establishments seemed, in the 1970s, a motley assortment, The Lodge being the only purpose-built residence, hastily thrown up before parliament moved from Melbourne to Canberra in 1927 and designed to accommodate the prime minister and his family – and intended to be temporary. Canberra’s Government House was originally the colonial homestead ‘Yarralumla’. With various additions and alterations, it has been described as ‘aesthetically erratic’. Admiralty House in Sydney began life as a bungalow, ‘Wotonga’, described by Howard Tanner as ‘dull, with no distinguishing features’. Purchased by the New South Wales government in 1885 with a view to its housing the commander-in-chief of the Australian Station of the Royal Navy, it acquired a second storey and colonnade, transforming it, would you believe, into a ‘grand Italianate palazzo’. With the formation of the Australian Navy in 1913, the last British Rear Admiral handed Admiralty House to the Commonwealth, which he had no right to do, but after decades of litigation and negotiation it ended up as the Sydney residence of the governor-general. Kirribilli House was a villa, ‘Sophienberg’, built by an enterprising young German businessman, Adolph Feez: Clive Lucas hails it as ‘a very pretty house on a very pretty site’. Subsequently, it was doubled in size. When the property was threatened with subdivision in 1920, the Commonwealth government intervened and resumed the property.

Nicholas Brown, author of A History of Canberra (2014), introducing ‘the bush capital’, wryly points out that the area chosen for it ‘was far from the most dynamic in the state’, and that, from the point of view of the New South Wales government, which was ceding the territory, it didn’t matter too much parting with it. While Peter Watts charts the chequered architectural life of ‘Yarralumla’, Margaret Betteridge has the task of dealing tactfully with a succession of prime ministers and their wives. Some virtually boycotted The Lodge and made other arrangements. The longest residents were Robert and Pattie Menzies, who, although they found it shabby and neglected, made it into a family home for sixteen years. There is a very posed photograph of them, Sir Robert solemnly reading a book, Dame Pattie concentrating on her knitting, both in their comfortable armchairs looking as if they have been there for sixteen years. If there is a bad fairy in Betteridge’s story, it is Zara Holt, who swept through the house redecorating it ‘Toorak style’; Harold Holt’s colleague Paul Hasluck thought it vulgar and in appalling taste.

The history of the beautiful harbour site of the Sydney establishments is briefly surveyed by Robert Griffin, and Howard Tanner and Clive Lucas detail the architectural fortunes of Admiralty House and Kirribilli House respectively. As both have had a hand in the houses’ renovation and restoration, they are necessarily constrained in the appraisals they can offer. However, as Lucas points out, in the postwar period Victorian architecture was viewed with distaste and renovation in ‘Georgian good taste’ common, but now ‘authentic restoration’ is the rule.

Nigel Erskine, John McPhee, Christopher Menz, and Andrew Montana take us on a historical tour of the collection. The entire book is laced with colour illustrations of paintings, sculptures, furniture and objects, and some of the detailed citations have interesting stories to tell. Menz, for example, points to the nineteenth-century fashion in elaborate silver epergnes (table centrepieces) often incorporating native flora and fauna, which were testimonial presentations to colonial worthies.

There is nothing in the nature of a conclusion to the book, and there are some unanswered questions. Some ‘artworks’ have been donated by descendants of distinguished personages, and while it is stressed that the Fund is autonomous, there is a casual reference to a ‘grant-in-aid’ from the government. Purchases are presumably initiated by the Art Advisor, but have priorities changed over forty years? There are, for example, notable absences. Although the Fund has a couple of contemporary Aboriginal paintings, there appear to be no traditional artefacts and nothing representative of Torres Strait Islanders. One art form not represented is photography. Why not a Bill Henson? Or would that be too ‘controversial’? And there is no indication of the Fund having anything related to one of our most important prime ministers, Alfred Deakin.

Collecting for the Nation is a handsome book, but at $79.99 it is likely to find its main market among independent collectors.

Comments powered by CComment