- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Science and Technology

- Custom Article Title: Danielle Clode reviews 'Charles Darwin: Victorian Mythmaker' by A.N. Wilson

- Custom Highlight Text:

Millions of words have been printed by and about Charles Darwin. There are hundreds of biographies, the dozens of books he wrote (including his own autobiography), as well as various pamphlets, essays, correspondence, diaries, manuscript notes, and other ephemera. Fascinating though the man and his work is, it must be hard to come up with anything ...

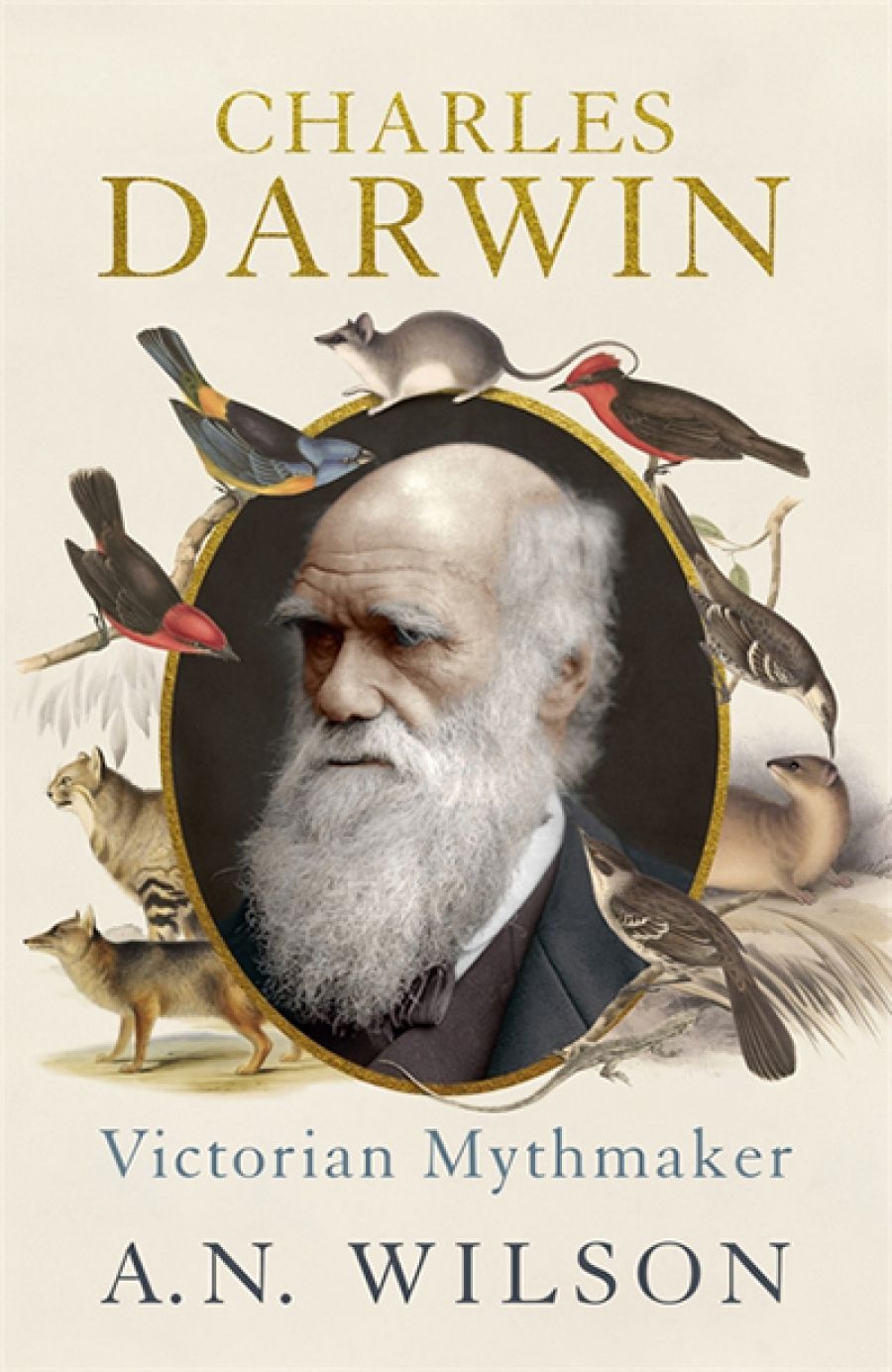

- Book 1 Title: Charles Darwin

- Book 1 Subtitle: Victorian Mythmaker

- Book 1 Biblio: John Murray, $48.99 hb, 438 pp, 9781444794885

Wilson exhibits many common misconceptions about science and evolution. He thinks that disagreements signify that the science is flawed, rather than in robust good health. He seems to be unclear about (or deliberately fudges) the difference between evolution and natural selection. He lurches through mangled discussions of punctuated equilibrium (the notion that evolution proceeds in sudden jumps rather than gradually), as if they disprove evolution by natural selection, rather than simply refining the details. He misjudges the depth of time and the rarity of fossilisation, believing that a lack of ‘missing links’ in the fossil record proves that gradual evolutionary change has not occurred.

Fortunately Wilson is on firmer ground when he sticks to biographical and historical detail. He is quite good on Victorian upper-class society, parochial though it is to classify the international development of evolutionary thought in the context of an English queen’s reign. When Wilson is not offering his own opinions on science and evolution, the book is engaging, nicely written, and feels authoritative and accurate, covering much the same ground as a great many other Darwin biographies. As a result, the book is strangely patchy, predominantly as competent and authoritative as we might expect from a biographer as experienced as Wilson, but punctuated by random twists of contorted logic and unsubstantiated conjecture.

Perhaps rather than trying to unpick the multitude of problematic conclusions that build from Wilson’s flawed assumptions (which many other reviewers have done in detail), it is more interesting to ask why Wilson chose to take this approach to his subject. Wilson’s problem with Darwin’s fallibility is puzzling. He doesn’t focus on the commonly accepted errors in Darwin’s work, but rather contends that a) evolution does not proceed as gradually as Darwin believed, and b) that evolutionary theory lead to a range of undesirable consequences such as Nazism. The notion that scientists should be held accountable for the gross misuse and distortion of their ideas by others is problematic, and certainly ahistorical. As to the issue of evolutionary gradualism, this is indeed one of the great unsolved debates in evolutionary theory, but just because Darwin didn’t solve everything doesn’t mean he was wrong or unimportant.

One of the reasons that punctuated equilibrium is contested is the lack of a convincing mechanism by which it might occur. It is one thing to have an idea about what is happening, another to explain how it might happen – which is, of course, precisely what Darwin provided for evolutionary theory. He hardly claimed to be the first to propose evolution – what he provided (alongside and inspired by many others) was a mechanism, natural selection, along with a vast amount of convincing evidence for it.

Caricature of Charles Darwin as a monkey on the cover of La Petite Lune, a Parisian satirical magazine published by André Gill from 1878 to 1879 (Bibliothèque nationale de France, via Wikimedia Commons)

Caricature of Charles Darwin as a monkey on the cover of La Petite Lune, a Parisian satirical magazine published by André Gill from 1878 to 1879 (Bibliothèque nationale de France, via Wikimedia Commons)

Why would Wilson expect Darwin to be saintly, perfect, or infallible? If we are going to engage in the kind of amateur psychoanalysis Wilson favours, perhaps it is because Wilson perceives Darwin as being such an important architect of ‘God’s funeral’ that he demands a more worthy replacement? Wilson’s track record certainly suggests a penchant for royalty and religion. The language of faith, rather than reason, is evident throughout this book. In an article in the Evening Standard, Wilson declared that ‘the ardent Darwinians ... would like us to believe that if you do not worship Darwin, you are some kind of nutter’. I think I know why the evolutionary biologists (only historians call them Darwinians) Wilson met might think he is eccentric, but I don’t think it has anything to do with Darwin-worship.

Perhaps it is just that Darwin is too popular for Wilson’s liking – a sacred cow ripe for journalistic slaughter. Wilson is not above accepting the conventional idolatry of great scientific figures: Linneaus, Owen, Lyell, and Cuvier are all presented uncritically in clichéd finery. Darwin’s actions, however, come in for detailed investigative scrutiny. Wilson returns repeatedly to the early death of Darwin’s mother as a cause of major psychological damage: eczema, social withdrawal, moodiness, intense competitiveness, egotism, and gastric illness. Darwin’s claim not to have any clear memory of her is not, according to Wilson, because he was only eight when she died, but because she taught her children botany and Darwin wished to depict himself as ‘self-taught’. Darwin’s self-confessed propensity to tell tall tales as a child is similarly taken as evidence of pathological lying rather than evidence of a curious and imaginative mind. Wilson is no more convincing as a psychologist than he is as a biologist.

Poor Darwin, it seems, is damned no matter what he does. Wilson complains that Darwin’s ‘diary gives no clue, and one gets no sense, when he visited Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Valparaiso, or Lima, that he pursued women. The lack of evidence suggests either very great discretion or very great restraint; if the latter, it was perhaps more easily achieved in one with very low libido.’ I am not entirely sure what Darwin’s libido has to do with the quality of his ideas, but it illustrates the kind of evidence Wilson provides to discredit Darwin’s work and character.

A photograph of Charles Darwin by Herbert Rose Barraud, taken in 1881, thought to be the last photograph of Darwin before his death. (Wikimedia Commons)

A photograph of Charles Darwin by Herbert Rose Barraud, taken in 1881, thought to be the last photograph of Darwin before his death. (Wikimedia Commons)

Geniuses are not always nice people, but everything I have read about Darwin (including in Wilson’s book) seems to suggest that he was a fairly nice bloke, if suffering from some health and anxiety issues. I can see nothing in this book that would make me think that Darwin was any more egomaniacal, dishonest, or sexually abnormal than, say, Linneaus. In neither case does this have much bearing on the quality and value of their work.

It is almost as if Wilson struggled to put an original spin on a fairly conventional and uncontroversial story. Perhaps, in the end, Wilson’s approach to Darwin was simply about getting attention and selling books. In which he has succeeded. What is new in this book is not convincing, and what is convincing is not new. There are many better biographies of Darwin to read. Save yourself from having to navigate the unnecessary spin in this one.

Comments powered by CComment