- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Custom Article Title: Miriam Cosic reviews 'The Unwomanly Face of War' by Svetlana Alexievich, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Svetlana Alexievich won the Nobel Prize in 2015, the response in the Anglophone world was general bewilderment. Who was she? The response in Russia was the opposite: intense, personal, targeted. Alexievich wasn’t a real writer, detractors said; she had only won the Nobel because the West loves critics of Putin ...

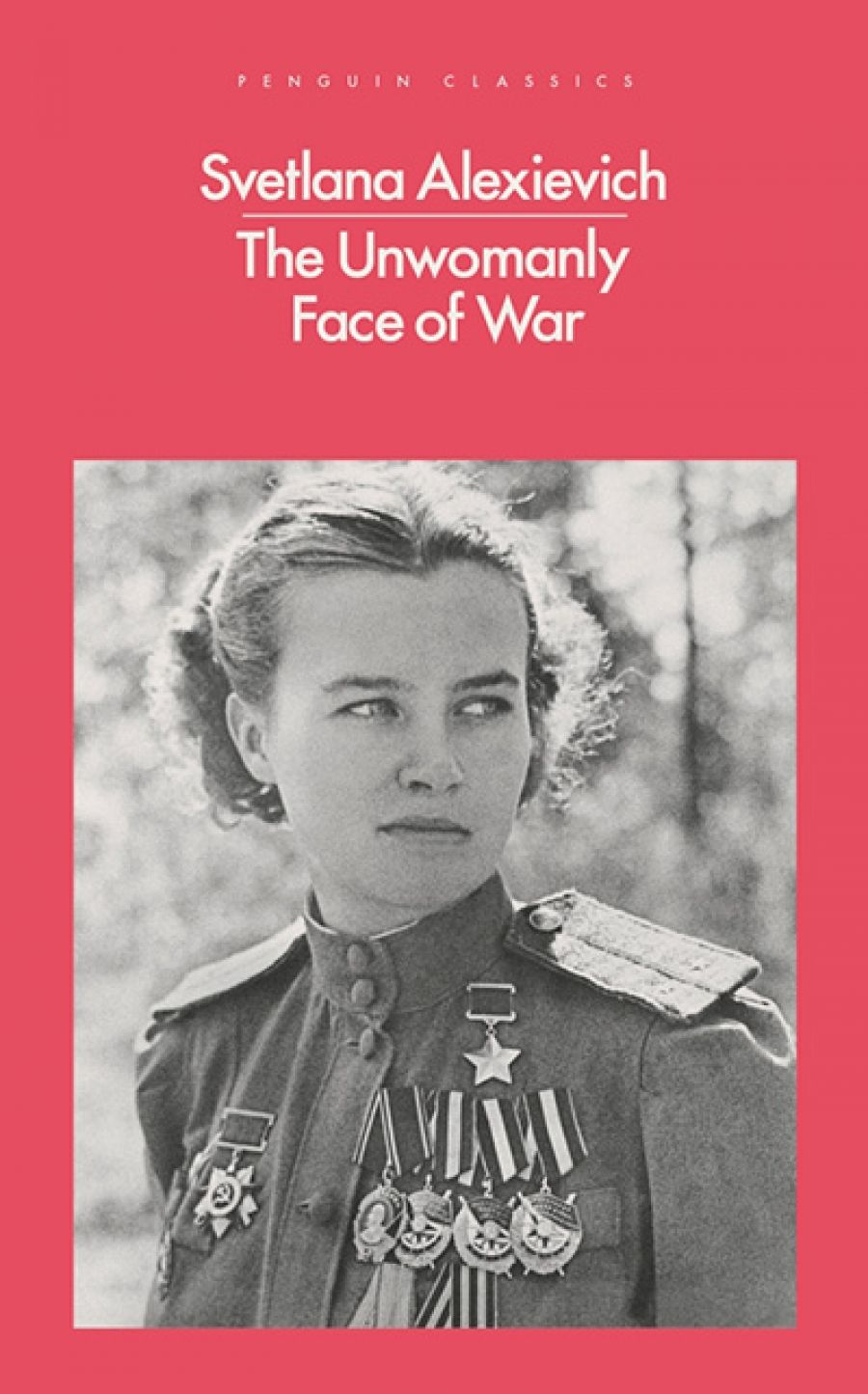

- Book 1 Title: The Unwomanly Face of War

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin Classics, $29.99 pb, 372 pp, 9780141983523

In her Nobel acceptance speech, Alexievich spoke of her own postwar childhood when the tired voices of village women, gathered on benches in the evening, would draw her in from play. ‘None of them had husbands, fathers or brothers. I don’t remember men in our village after World War II: during the war, one out of four Belarusians perished, either fighting at the front or with the partisans ... What I remember most, is that women talked about love, not death. They would tell stories about saying goodbye to the men they loved the day before they went to war, they would talk about waiting for them, and how they were still waiting. Years had passed, but they continued to wait: “I don’t care if he lost his arms and legs, I’ll carry him.” No arms ... no legs ... I think I’ve known what love is since childhood.’

The Unwomanly Face of War is about the other women, those who went to war themselves, whose voices were not heard for decades afterwards: the officers, snipers, pilots, mechanics, and nurses whose stories she collected between 1978 and 2004.

The book was published in Russian in 1985 and sold two million copies. Only now has it been translated into English, by the widely admired team of Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. It is raw, anachronistic, but all the more interesting in a time of blanket propaganda from Russia, which gyrates between eras – devout Orthodoxy under the tsars, military might under the Soviets – to further its nationalist aims. It is of particular importance to women, and anyone interested in them, because it demonstrates their equality with men, even in the field of war, in a country that now negates the gender-free egalitarian ideals of the Soviet era even more than the Soviet era, in reality, did.

And yet, the women’s preoccupations unwinding across the pages, barely edited except for chapter headings that group them under certain topics, come as a surprise. As they lower their guard and speak freely, they often downplay their fighting role. They seem most eager to discuss the absence of love and beauty while they were in the military: those traditional pursuits or preoccupations when they had no place in war or business or politics. When we do hear of their wartime work, it is often by way of modest bragging to show how misplaced masculine assumptions were about women’s competence and bravery.

So many commanders were furious when women departed from protocol to, say, don earrings in celebration of a successful manoeuvre. ‘Have you come to fight or to a ball?’ shouted one. ‘I need soldiers, not ladies. Ladies don’t survive in a war.’ The interviewee – Anastasia Petrovna Sheleg, junior sergeant and aerostat operator – allows herself a wry comment: ‘Before the war, he had been a maths teacher ...’

Double standards still dog women working in traditionally male fields, including here in Australia. But the poignancy of these women’s desire for love and interest in hairdressing, make-up, and jewellery is a constant counterpoint to their descriptions of fighting. So is the knowledge that, however many medals they might earn, the almost incalculable male casualties during the war, plus their own physical and psychological injuries, would affect their marriageability, and thus their future, after the war.

Members of the Sydir Kovpak partisan detachment, 1940s (Wikimedia Commons)

Members of the Sydir Kovpak partisan detachment, 1940s (Wikimedia Commons)

‘He used to tell us that in war soldiers were called for and only soldiers,’ said Maria Nikolaevna Shchelokova, sergeant and commander of a communications unit, of her own commander. ‘But we also wanted to be beautiful ... All through the war, I was afraid I was going to be hit in the legs and get crippled. I had beautiful legs. What is it for a man? Even if he loses his legs, it’s not so terrible. He’s a hero anyway. He can marry! But if a woman is crippled, it’s her destiny that’s at stake.’ It is a terrible counterpoint to Alexievich’s Nobel speech.

Others talked of what we now would call PTSD. One woman, a car and tank mechanic who had worked at the front, recalls being told later by a neuropathologist that he had never seen such a wrecked nervous system in a twenty-four-year old. ‘How are you going to live?’ he asked her.

Live she did. She went to university after the war, though it became ‘a second Stalingrad’ for her: ‘I finished it a year early, otherwise I would have run out of energy. Four years in the same overcoat – winter, spring, autumn – and an army shirt so faded it looked white ... Ah, fuck it all.’

Comments powered by CComment