- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Custom Article Title: Louis Klee reviews 'Blind Spot' by Teju Cole

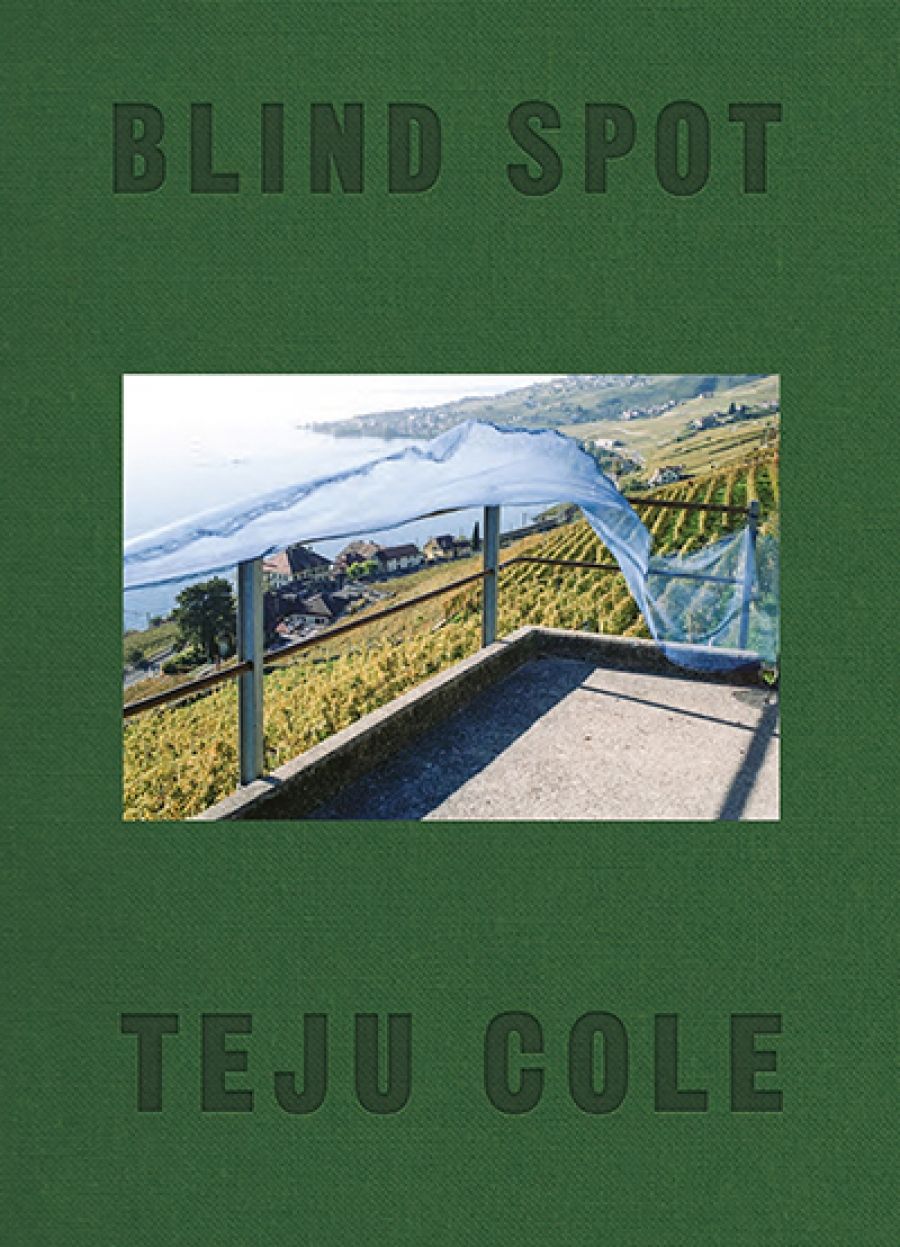

- Book 1 Title: Blind Spot

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber & Faber, $39.99 hb, 352 pp, 9780571335015

This is one of 150 counterpoints of original photographs and ruminative fragments of prose that make up Cole’s fourth book, Blind Spot. It is a project defined by a deft observation of the everyday, an abiding interest in the woundedness of history, and an openness to the unexpected echoes amongst things. Masterfully, these features emerge through a series of textual allusions and recurring visual motifs – ladders, drapery, cars, the detritus of human presence – drawn from his travels across the globe, from São Paulo, Lagos, and Berlin, to Brazzaville, Auckland, and Beirut.

When I speak to him about his new book, he notes: ‘the ideal of reading is to read something in a troubled way’. By questioning our received ways of making sense of the world, Blind Spot troubles in the most edifying and urgent sense; in the hope, perhaps, of recalibrating us to see and read anew.

The project began in 2011 – ‘one fine morning in my mid-thirties’, as Cole puts it – when he woke up partially blind. He was diagnosed with papillophlebitis, or ‘big blind spot syndrome’. Although the grey that shrouded his left eye has retreated, he lives with the knowledge that it may return. This incident occurred two months after the completion of his celebrated novel Open City (2011) and drew him deeper into one of its driving concerns: what are the limits of our knowledge and vision?

In Cole’s latest book, the ‘blind spot’ becomes a powerful and ubiquitous metaphor, a placeholder for everything from the shortcomings of the camera – its mechanical failures, distortions, and illusions – through to what he calls the ‘moral exigency [to] compel what was hidden to become visible’; to acknowledge that which cannot be said nor made visible at all. Yes, we may see the world, but Cole draws us back to the questions: ‘Which world? See how? We who?’

What I find immediately striking about the book, I tell him, is its distinctive use of form. ‘I have a feeling of responsibility,’ he replies, ‘not toward experimentation, but freedom. I wanted to have the courage of my own form.’ To push the conventions of a genre, even an emergent online medium like Twitter, has been an enduring feature of his work. It is what makes Blind Spot feel at once singular, of a genre of its own making, and yet so unmistakably Cole.

Like his earlier works, it builds meaning through ‘disciplined association’. But ‘by the time I got to Blind Spot,’ he explains, ‘I wanted the jumps to be bolder.’ It is through these leaps and elisions that Cole’s book grapples with history and politics. The draped bulk of a vehicle in Ubud becomes a makeshift memorial to the Indonesian mass killings of 1965; five metal chairs pressed between a van and a fire hydrant stand-in for a Black Lives Matter protest; even the silent tranquillity of Swiss mountainscape becomes imbued with the unseen violence of the country’s arms sales and its legacy of child slave labour. What gives this technique its harrowing currency is perhaps best captured by a poem from Tomas Tranströmer that Cole is fond of citing: ‘often the shadow seems more real than the body / The samurai looks insignificant / beside his armor of black dragon scales.’

Teju Cole (photogaph by Lorianne Di Sabato, Flickr)

Teju Cole (photogaph by Lorianne Di Sabato, Flickr)

Cole’s pairings of image and text have a quiet mystery that moves between meanings. The rhyme between the stance of two men in a park in Berlin; a woman glimpsed from behind on the streets of Manhattan – these provoke not only speculations on the lives of others, but on how others imagine our lives in turn. Early in Blind Spot, Cole offers a definition of the human being as ‘the animal that can mourn strangers’. In spite of our blind spots, the human imagination reaches out to the other, but it is an other that can see us, read us, and mourn us too.

‘What about a question on Australia?’ he says finally. Australia is not pictured in Blind Spot, but when Cole travelled here he drove out to Goroke through the Victorian plains to visit the reclusive novelist Gerald Murnane, the music of Peter Sculthorpe echoing in his ears. In the postscript to Blind Spot, he writes: ‘I am intrigued by the continuity of places, by the singing line that connects them all.’ I press him on this and he laughs. ‘Absolutely, it’s an allusion.’ From Indigenous Australians, he says, he takes an inspiration for something at the core of his project: ‘to be the opposite of a bureaucrat, to be someone who has an intense engagement with the allusive aspects of being and place’.

Comments powered by CComment