- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Architecture

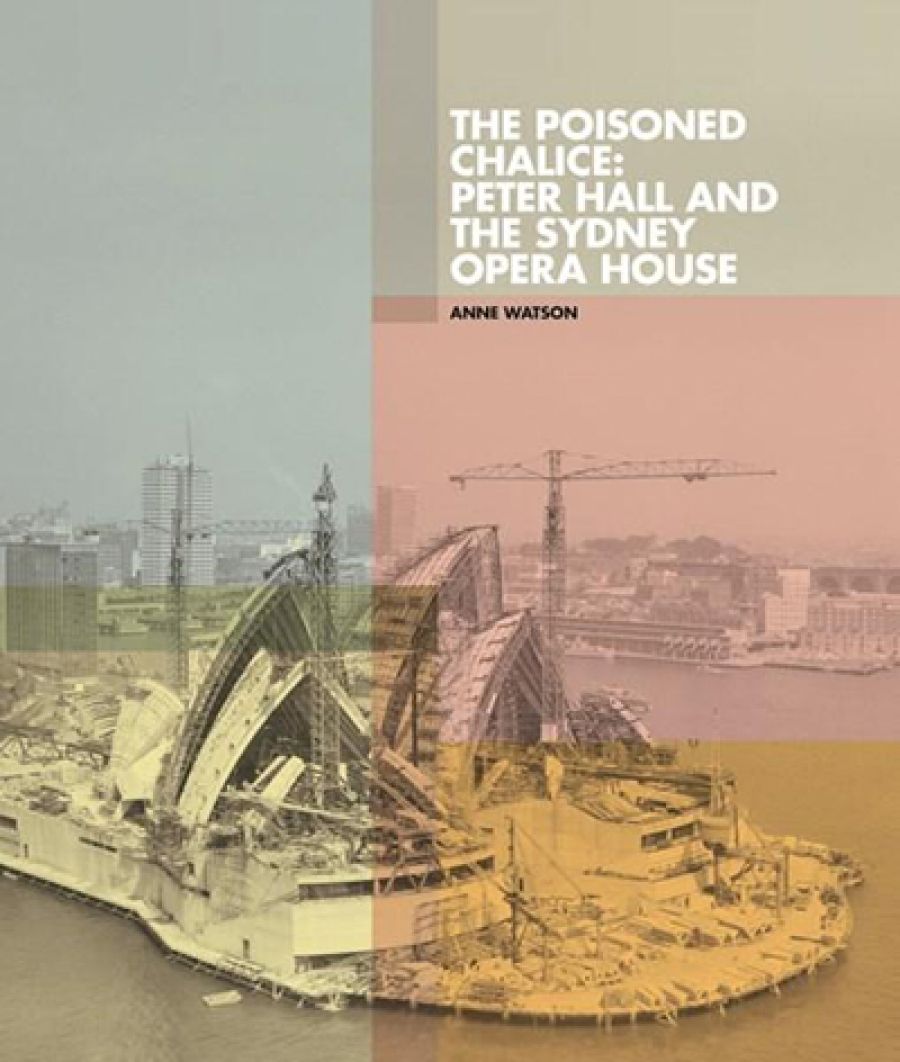

- Custom Article Title: Andrew Montana reviews 'The Poisoned Chalice: Peter Hall and the Sydney Opera House' by Anne Watson

- Custom Highlight Text:

Researching Australia’s most iconic building and writing about its beleaguered history from the time Jørn Utzon resigned in 1966 until it opened in 1973 might result in an indigestible plot for many of the building’s enthusiasts. Yet narrating the fraught circumstances behind the completion of the Sydney Opera House by Australian ...

- Book 1 Title: The Poisoned Chalice

- Book 1 Subtitle: Peter Hall and the Sydney Opera House

- Book 1 Biblio: OpusSOH, $59 hb, 244 pp, 978064696739

First and foremost, the book exposes and examines the poisoned chalice. Everyone, at some stage, drinks from this chalice. It was left to Hall to remove its toxic potency whilst simultaneously, and knowingly, sipping it. So what was the poison chalice? Controversially, it was the incomplete SOH building. Exit Utzon (almost), and the problems were glaringly obvious. How does an architect make interiors for their performative function, when this should have been designed before the outward form? Should the Major Hall (renamed the Concert Hall) retain its proposed function as a multi-purpose auditorium or not? The paramount difficulty would be the interior’s conversion from an opera stage to a concert hall with a fixed proscenium arch used primarily for symphony concerts.

Should the Minor Hall (later renamed the Opera Theatre) retain its proposed primary function as a drama theatre or should it become the main opera venue? This would be difficult because the stage and pit were small and audience accommodation would be tight. The exterior having been conceived before the interiors were designed, Utzon’s project became, arguably, a modernist mishap. Interwoven with these heated questions was the future viability of opera in Australia. Was it a dead art form and if so what performing arts genres would the SOH serve? Should the building be called the Sydney Arts Centre? Fortunately it wasn’t, and the half-baked briefs from the SOH Trust were compounded by the lack of considered input from the Elizabethan Theatre Trust and the strategic threats of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra to remain at the Town Hall.

Lionel Todd, David Littlemore, and Peter Hall photographed by Max Dupain, early 1970s (image courtesy of State Library NSW)Careful never to vilify Utzon, Watson emphasises how Hall’s deference included following Utzon’s preparatory procedures of model-making to investigate the master’s ideas and, significantly, how Hall attempted to find ways to translate these for the interiors and northern windows into built form. Proving impossible, these concepts were wisely abandoned. From the start, Utzon’s conceptual winning design in the 1950s was, according to Watson, a ‘sublime, but essentially unbuildable competition entry’. Indeed, the central paradox was that if pre-planning, design and control had occurred initially, Uzton’s SOH might never have set sail in the first place.

Lionel Todd, David Littlemore, and Peter Hall photographed by Max Dupain, early 1970s (image courtesy of State Library NSW)Careful never to vilify Utzon, Watson emphasises how Hall’s deference included following Utzon’s preparatory procedures of model-making to investigate the master’s ideas and, significantly, how Hall attempted to find ways to translate these for the interiors and northern windows into built form. Proving impossible, these concepts were wisely abandoned. From the start, Utzon’s conceptual winning design in the 1950s was, according to Watson, a ‘sublime, but essentially unbuildable competition entry’. Indeed, the central paradox was that if pre-planning, design and control had occurred initially, Uzton’s SOH might never have set sail in the first place.

Like probing the growth of an organism, the book uncovers Hall’s efforts to make the interior spaces integrated and working respective wholes. In collaboration, Hall assiduously researched the materials, the prototypes, the acoustics, the sound reverberations, the technologies, the weights and balances, the sight levels and the configuration of seating. Models were made for analysis before any part was committed to a working drawing and contracts were issued. Too often, these later stages were abandoned.

The Sydney Opera House under construction (OpusSOH)The SOH’s construction was a web of entanglement between architects, engineers, stakeholders, advisors, bureaucrats, government departments, manufactures, NSW state politicians and ministers, press reporters, designers, consultants, and acoustic specialists. The indecisions, restrictions, blunders, misinterpretations, political and power struggles, and miscommunication make for exhausting and at times disturbing reading. But again, Watson never set out to tell a pretty tale. Ultimately, she draws a balanced and instructive account of Hall’s collaborations, compromises, negotiations, resolutions, and inventions. Clearly, Hall’s task was a juggling act between aesthetics and pragmatics, architect and client, and, not surprisingly, architect and engineer. Hall arrived at solutions for the interiors and northern glass walls through an expression of their function in structure and form. Eschewing speculations about what Utzon might have achieved if the public ‘bring Utzon back’ campaign had been successful, Watson determines what Hall and his team achieved – against the odds.

The Sydney Opera House under construction (OpusSOH)The SOH’s construction was a web of entanglement between architects, engineers, stakeholders, advisors, bureaucrats, government departments, manufactures, NSW state politicians and ministers, press reporters, designers, consultants, and acoustic specialists. The indecisions, restrictions, blunders, misinterpretations, political and power struggles, and miscommunication make for exhausting and at times disturbing reading. But again, Watson never set out to tell a pretty tale. Ultimately, she draws a balanced and instructive account of Hall’s collaborations, compromises, negotiations, resolutions, and inventions. Clearly, Hall’s task was a juggling act between aesthetics and pragmatics, architect and client, and, not surprisingly, architect and engineer. Hall arrived at solutions for the interiors and northern glass walls through an expression of their function in structure and form. Eschewing speculations about what Utzon might have achieved if the public ‘bring Utzon back’ campaign had been successful, Watson determines what Hall and his team achieved – against the odds.

Tragically, the residue from the poison chalice contaminated some of the rank and file of the architectural profession – and Hall himself. Inextricably linked, the negative responses to Hall’s endeavour and his subsequent near erasure from histories and celebrations of the SOH compromised his ongoing career and his health. With resolution, Watson weaves a strident new narrative, an unswerving thesis in Hall’s defence, on his completion of the SOH. Through his integrity and unfaltering commitment to finishing a magnificent building in the service of the arts, Hall, with courage and flair, emerges as a reasoned and expressive ‘form follows function’ architect. His achievement and legacy are made unquestionable but not beyond ongoing debate.

Comments powered by CComment