- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

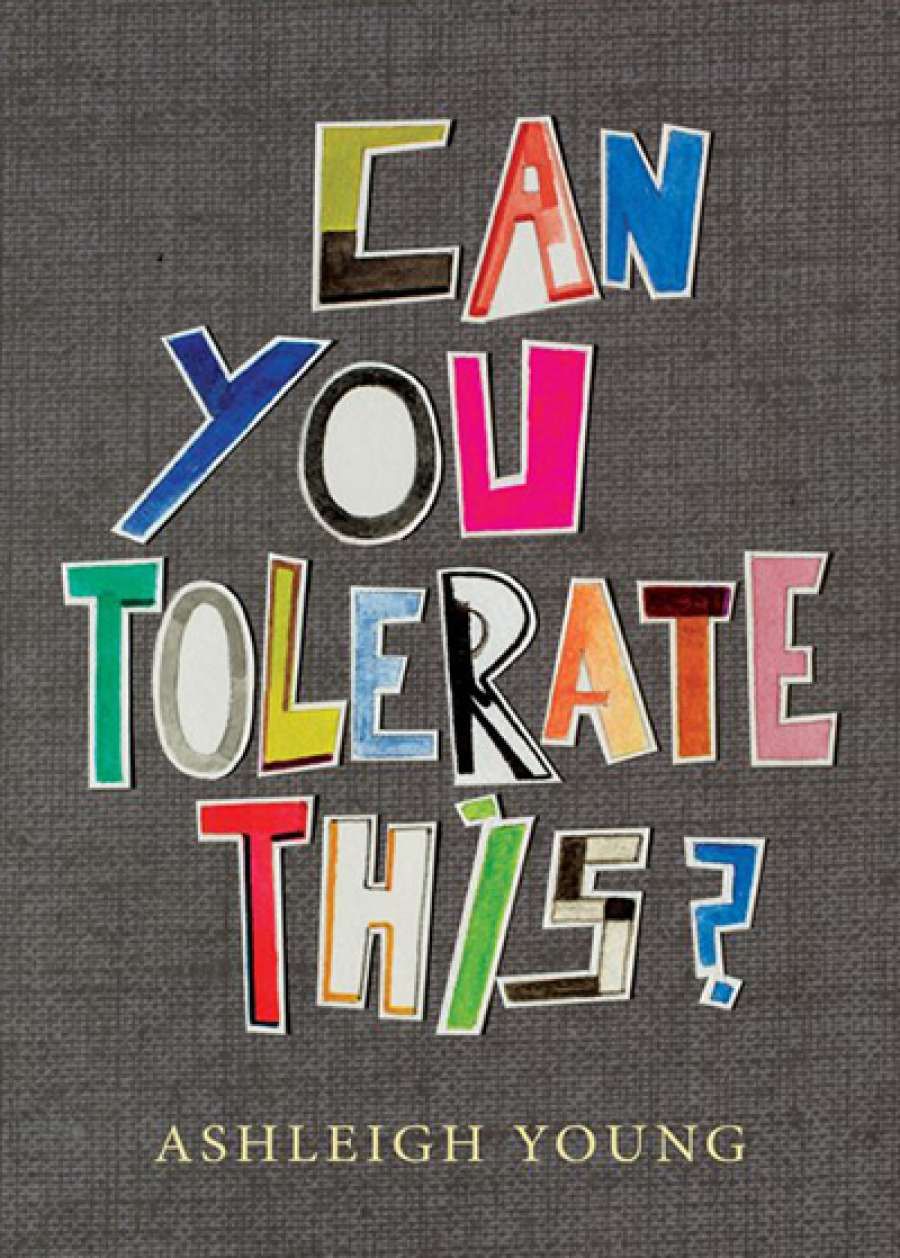

- Custom Article Title: Mark Williams reviews 'Can You Tolerate This?: Personal essays' by Ashleigh Young

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Can You Tolerate This?:

- Book 1 Subtitle: Personal essays

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24.95 pb, 280 pp, 9781925336443

Much of the book centres on the writer’s preoccupation with the body and its dissatisfactions, around which philosophical and medical discourses gather. ‘Bones’ frames the concern by recounting the life of a boy with a hideous disability; from the age of five, a ‘second skeleton’ grows around his natal one. An unsettling agency is ascribed by Young to this extra skeleton that ‘seemed to want to fuse him to a single spot and keep him safe there’.

For New Zealand readers, the image of the dead boy displayed in a museum, his bones fused without the aid of wire, might recall Allen Curnow’s famous poem ‘The Skeleton of the Great Moa in the Canterbury Museum’ or Bill Manhire’s ‘Phar Lap’ where the bones of the great horse in the National Museum stand, articulated. Young, as an editor at Victoria University Press, will know the echoes, but her purpose is not to engage in intertextual teasers or bow before her national literary ancestors (in ‘Katherine Would Approve’ she neatly eviscerates the genteel literary worshippers of a faux Mansfield by recounting her time working in the great one’s birthplace and shrine). ‘Bones’ directs our attention to the actual person visited by suffering more extreme but no more arbitrary than that of any human life, and to the writer thinking about bodily imperfection.

Worried bodily self-consciousness is insistent in these stories, the writer herself suffering from (parent-induced) hair and weight anxieties. These personal anxieties are placed alongside narratives of extreme abnormality, like that of the ‘Hairy Maid’. The body, though, is not all painful self-regard. In ‘Witches’, the author recalls early childhood when ‘Each of us begins in the nude.’ The children look at the world of parents, place, and things, but not inwards – ‘at everything but ourselves’. Before the fall into self-consciousness, the body feels ‘inconsequential’. After, it carries a personal sense of imposition, even imprisonment; it becomes an extra skeleton, ‘a thing both apart from and forever clinging to our back’.

Reading these essays at times recalls Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women transposed from small-town Ontario to a kiwi parochialism. But the essays are not fictive. The author is a poet, so literature is part of the personal life explored, along with philosophical and ethical thinking. And Te Kuiti, the scene of the writer’s childhood, is not a fictional version of an actual place. In the rich dairy land of ‘The King Country’ (where the Māori king and his followers went into exile after the British conquered the Waikato), the writer’s family straddles the distances between town and country, accountancy and farming. Growing up sensitive, Young is not wholly isolated. She has her brothers with their bands, music, and eccentricities, and she has an imaginary friend. Walking the hills near Te Kuiti, the author imagines herself discoursing with Paul McCartney before his face began its ‘slow collapse’. As his teenage understander, she transports herself into the larger world, and the gap discovered between local and worldly is both immense and intimate: ‘I wanted to walk beside someone from a different universe, someone who would turn Te Kuiti into something else.’ In fact, she moves to Wellington, a cultural city in its own right.

Ashleigh Young

Ashleigh Young

Provincialism, for Young, is not where you are; we all live, as Manhire puts it, ‘at the edge of the universe’. Listening to old tapes she recognises ‘a Romanticism of the King Country: it was as if this place, for my father and his friends, was as potent as Liverpool in the 1960s’. Here, the dream of escape is linked to another province imagined as a centre, another unexpectedly generative province of the cramped soul.

In Maurice Duggan’s 1963 story ‘Along Rideout Road That Summer’, the narrator, an educated young man working for a summer on a farm, rides an ancient tractor while intoning ‘Kubla Khan’ and watching the farmer’s beautiful daughter, Fanny Hohepa. His problem, ‘How to connect...’, is also one for our essayist who recalls wishing to ‘turn Te Kuiti into something else. Its army-blanket green would become a romantic backdrop.’ But kiwi romanticism is not endorsed, and the older Young prefers the dangers of biking around Wellington to the boredom of the bush walk. Te Kuiti, Liverpool, Wellington – in these naked, beautiful essays about self and its exoskeletons, where one is and where one longs to be, Ashleigh Young has connected unlikely parts.

Comments powered by CComment