- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The happy few

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As Stendhal did with The Red and the Black (1830) and The Charterhouse of Parma (1839), Simon Leys dedicates his With Stendhal to ‘the happy few’. In both cases, humility is the motivation, rather than affectation or coyness. Henri Beyle (1783–1842) – Stendhal’s real name – was committed to his writing, but he really had no idea that his novels would become masterworks of Western literature, or that his protagonists Julien Sorel and Fabrice del Dongo would come to be seen as archetypal figures of the Romantic era. He would have been astonished to learn that beylisme – denoting a melding of passionate energy and cynical individualism – had become a common noun in French.

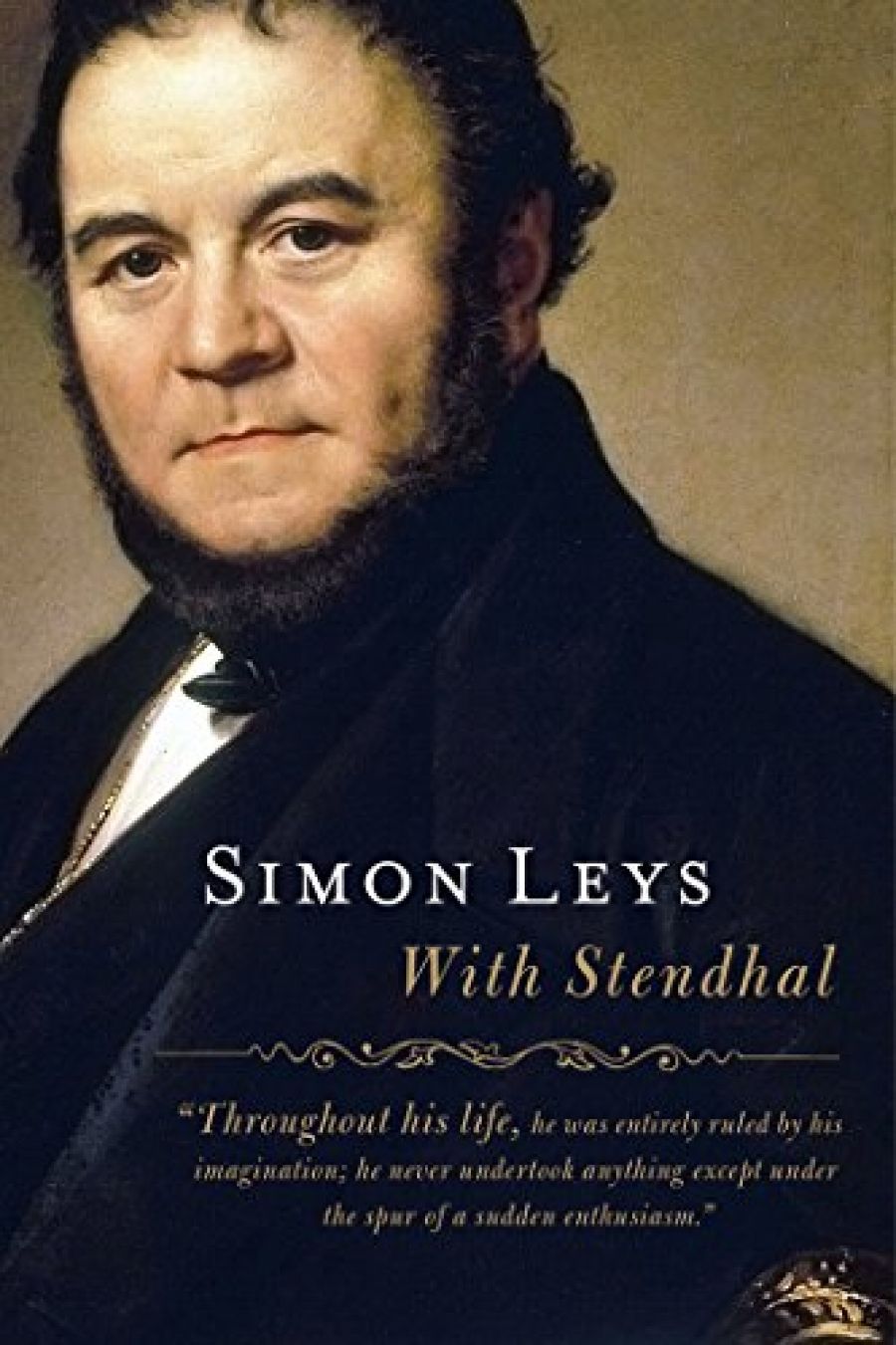

- Book 1 Title: With Stendhal

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $19.95 pb, 144 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Leys, for his part, has directed his own great erudition and literary talent to translating, presenting and annotating two short texts previously unavailable to English-speaking Stendhal admirers. Each – the 1874 version of Prosper Mérimée’s Henri Beyle (Stendhal) and Stendhal’s own The Privileges (written in 1840) – is well enough known within the French tradition, but to make them so much more widely accessible is an elegant contribution to literary culture as a whole. It reminds us of the conundrum at the core of any approach to Stendhal: namely, the constant flicker-ing of focus between the writing and the author’s life, and the impossibility of resolving those ambiguities. As Leys points out, Stendhal is one of those writers whose unexpectedness draws attention to an originality of heart and mind that makes people want to know more about what he was like in the real world; the pieces presented here help do just that. In an appendix, Leys includes a third perspective, with a snippet (in his own translation) from George Sand’s brilliant and insufficiently known Story of My Life (1855).

Mérimée’s portrait of his long-time friend was written as an act of homage and mourning. It is at once warm with love and full of anecdotes that show what a complicated and paradoxical person Beyle was: a man who hated authority but admired Napoleon; one who lived for the heart but who insisted that logic should guide all things and who had a maxim for all occasions; one who was passionate about music but quite deaf to poetry; one who willingly played the fool at social gatherings but who, as a soldier facing real dangers in the Napoleonic campaigns (including Russia), was as cool-headed as he was courageous.

Mérimée also admires the fact that Beyle, although writing and rewriting compulsively, never seemed hurt by criticism of his work. Of course, for Mérimée, as for George Sand and most other contemporaries, such criticism was justified, because Beyle ‘wrote badly’. Mérimée did imagine that some recognition might come in the twentieth century, but really valued only the correspondence, which he hoped to see published: ‘then readers would learn to know and love a man whose wit and excellent qualities survive now only in the memory of a small number of friends.’

Leys opines that, despite the sharpness of his observations, Mérimée ‘missed the essential thing: Stendhal’s genius’. He believes that Mérimée might have known better, both because of his hugely competent work in the preservation of some of France’s most beautiful and valuable monuments (Vézelay cathedral, the stained glass of Chartres) and because of his own status as one of the major writers of his day (which included being a member of the Académie Française). For Leys, this misjudgement may simply have resulted from Mérimée’s being too close to his subject. That is plausible, for Mérimée’s text does celebrate in the man – beyond the inveterate womaniser, the excessive drinker and the snob who believed that those guilty of bad taste or tediousness should be executed – the very qualities that many would use to define Stendhal’s genius as a writer: the absolute lack of contrivance; the originality of the committed ‘observer of the human heart’; the passionate spontaneity; the great gift for narrative; and, above all, the radical freedom of spirit.

Compared to Mérimée’s portrait, the George Sand sketch is very impressionistic. She and her poet lover Musset shared a boat journey with Beyle on the Rhône in 1833. She picks up on his temperamental extremes, noting a wildly joyous postprandial dance in a village inn after he has drunk too much, and a bout of fury over a grotesquely realistic statue of Christ discovered in a church in Avignon. Although she acknowledged his eminence, his wit and his penetrating mind, she found him unbalanced and was glad to see the back of him when their ways parted. She was not yet thirty, and saw him (at fifty-three) as a bawdy old man. While granting him a certain amount of originality and talent, she writes nothing suggesting awareness that she had encountered one of the great writers of the age. But then, as we have already seen, most of his contemporaries felt the same way. Leys cites Victor Hugo at the time of Stendhal’s death: ‘Mr Stendhal will not reach posterity, because he never had the faintest inkling what writing is.’

The Privileges is an improvisation, dashed off one day in Rome, a couple of years before Stendhal’s death. It was not meant for publication, and we do not know whether Stendhal kept it by design or chance. On one level, this collection of twenty-three ‘articles’ is simply a playful parody of the sorts of administrative documents that Beyle must have dealt with frequently in his work as a consular official in the Papal States. Full of contorted, finicky pseudo-legalese, they smack of an act of escapism on the part of a man stifled by daily tedium. At the same time, as Leys stresses, they are quite revealing about the writer’s underlying preoccupations with death, love, and his own ageing and physical unattractiveness. Individually, they could appear infantile or even silly, with their announcements of gifts of mind-reading, speed travel, transformation into other creatures, multilingualism, or skills in hunting and duelling. Cumulatively, however, they become quite mesmerising in their strangeness, markers of a unique imagination that darts about feverishly and fearlessly, constantly seeking new mental territory. While much in Stendhal types him as a Romantic, there is something startlingly modern in The Privileges, something akin to Rimbaud’s systematic undoing of givens, and to the ‘pataphysical’ mentality we find in the writings of Alfred Jarry, Eric Satie and Boris Vian.

It will be seen that, although generally self-effacing in his commentary and notes, Leys is fortunately not absent. His presence is very much a writerly one. Occasionally, strong personal aesthetic opinions surge up to confront the reader, as in his note on Carmen: ‘Bizet’s opera remains hugely successful all over the world; yet both music and libretto are grossly inferior to Mérimée’s stylish masterpiece.’ More importantly, With Stendhal – the translations, the presentations, the carefully documented notes – is testimony to a generous breadth of humanity that should be admired and treasured. It is a delight and a profound reassurance that the man who once taught Chinese to an Australian prime minister should so attentively share the pleasure he derives from the company of a nineteenth-century French novelist.

Comments powered by CComment