- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Human uplift

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

During Harry Houdini’s 1910 visit, the famous escapologist claimed to be the first person to achieve powered, controlled flight in Australia. In Houdini’s Flight, Angelo Loukakis uses these bare details as the backdrop for a modern tale about a more modest achiever, Terry Voulos. A second-generation Greek-Australian, Terry confronts, almost in slow motion, a personal crisis that initially seems caused by his own stuttering approach to life. Whereas Houdini descends into water to release himself from heavy chains, Terry must break free from his own limitations to revitalise his life, his attitudes, his marriage to Jenny and his bond with his son, Ricky.

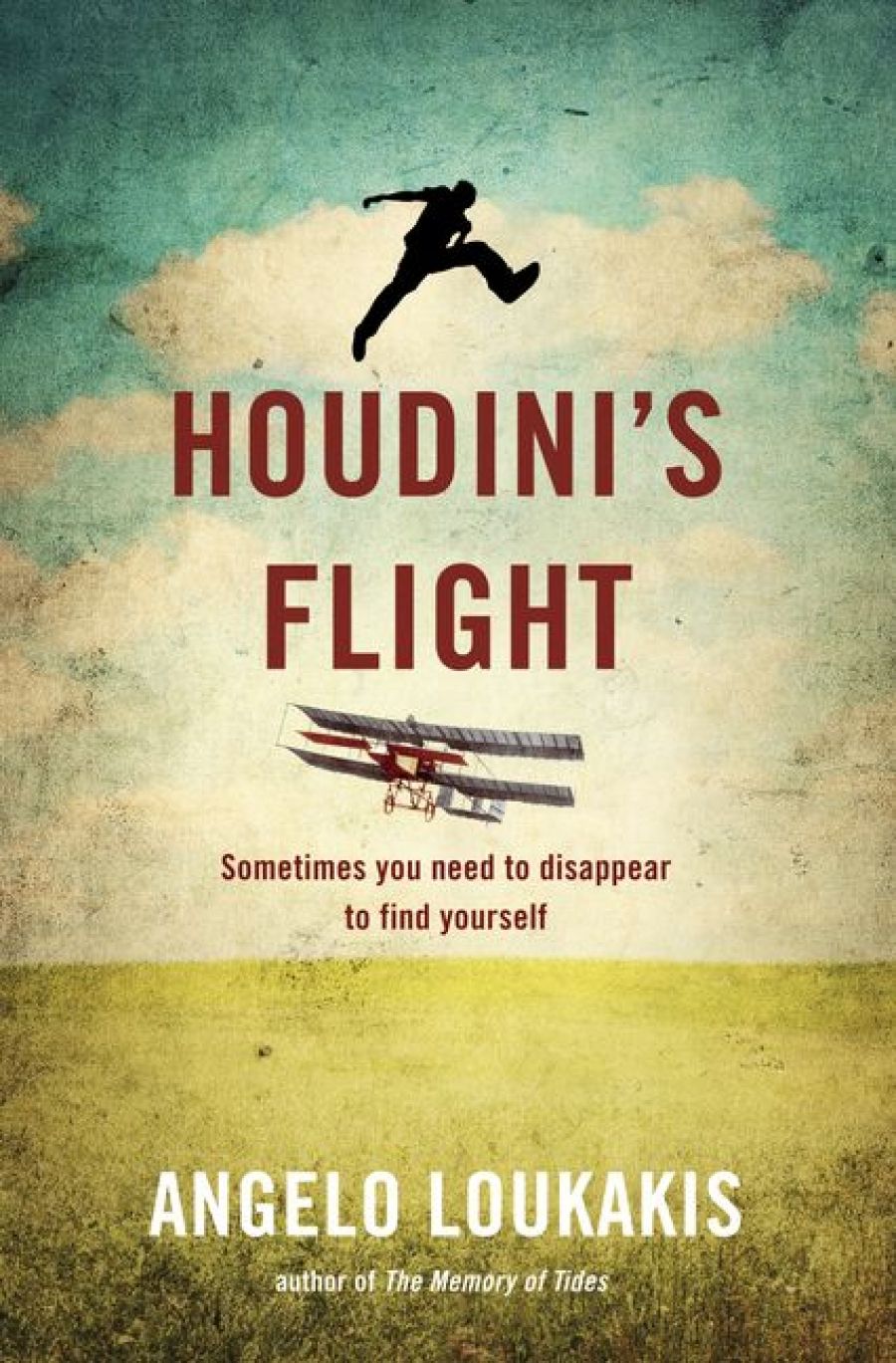

- Book 1 Title: Houdini’s Flight

- Book 1 Biblio: $32.99, 352 pp

At its core, Houdini’s Flight is about the complex bond that develops between Terry and Hal. It is hard to tell which man needs the other’s help and companionship more. But Loukakis has created a moral fable, full of themes, ideas and plotlines. He uses Terry’s predicament to ponder the difficulties some men have in communicating with their loved ones, and Hal’s rundown status to consider how hard some men find it to deal with the everyday and to avoid alcohol. He also reflects on post-World War II Greek immigration to Australia, on secrets, lies and violence within families, and on the reverberating effects of a tragic accident. Not least, he offers a rich portrait of the city of Sydney.

If all this makes Houdini’s Flight sound more like an essay or a socio-political study, it is true that Loukakis’s characters occasionally behave, and the plot seems to shift, in ways designed to help probe and contextualise various themes and ideas. But if the story sometimes has a slightly contrived feel to it, this may just reflect the agendas and the secrets harboured by various characters: Terry is fixated on transforming himself into a different, better person, while Hal, it turns out, has a great deal more to tell Terry than at first seems possible.

In any case, whatever didacticism exists is periodic and partial, and rarely overwhelms the narrative or disturbs the gentle, understated prose. Most especially, Loukakis builds a subtle portrait of Terry as he sets about staring down his emotional baggage, wading into the ugly past and confronting with quiet and methodical determination its impact on his and Hal’s lives.

Terry’s desire to be a better man stands in stark contrast to the behaviour of his elderly father, Stavros. The struggle between father and son is genuinely painful to observe, and the dialogue between them is riveting and ugly. Stavros’s brutal verbal assaults pulsate with naked aggression and remind Terry of the physical beatings he endured as a child. The more Terry learns about Stavros’s past – and in Houdini’s Flight everything turns out to be connected and causal – the more despicable a man and a father he seems, though as an old man he is also vulnerable and shrunken. Their confrontations, especially the last meeting, represent the novel’s most powerful moments. In contrast, Terry’s interactions with Jenny, especially after they are estranged, are less emotionally complex and raw.

In Houdini’s Flight, Loukakis invites readers to consider a key question: is the world of magic, despite its intention to make one thing seem another, more honourable than the real world? At times, the narrator’s rather overt efforts to compare and contrast magic and life seem like strategic billboards. For example, while standing under the Harbour Bridge, Hal awkwardly opines that magic is like a bridge because both are ‘A span that joins two otherwise un-connected things’. More often, though, magic provides much of the story’s shape, mood and energy.

Houdini’s legacy casts a long shadow over Terry and Hal – his greatness and his celebrity captivate both men. While Hal’s talks of Houdini occasionally seem to impose themselves on a novel that is doing fine by itself, it is Houdini’s life that inspires Terry to reinvent himself. Houdini might be a genius, but Hal and Terry also idealise him as a man for whom actions speak louder than words, a man ‘determined to be free in the face of any odds’. Significantly, the achievement of Houdini’s that Terry decides to recreate is no trick – what you see is what you get.

Soon after they meet, Hal tells Terry ‘for a story to make sense is like for a trick to work; the audience has to be ready and ripe for it. The audience has to need this for themselves.’ The climax of Houdini’s Flight isn’t especially believable, but it hardly matters: it is an uplifting (literally), fun and heart-warming moment, and a quietly triumphant conclusion to a book in which enthusiasm for magic commingles with sober reflections on how we might live extraordinarily in the everyday world.

Comments powered by CComment