- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

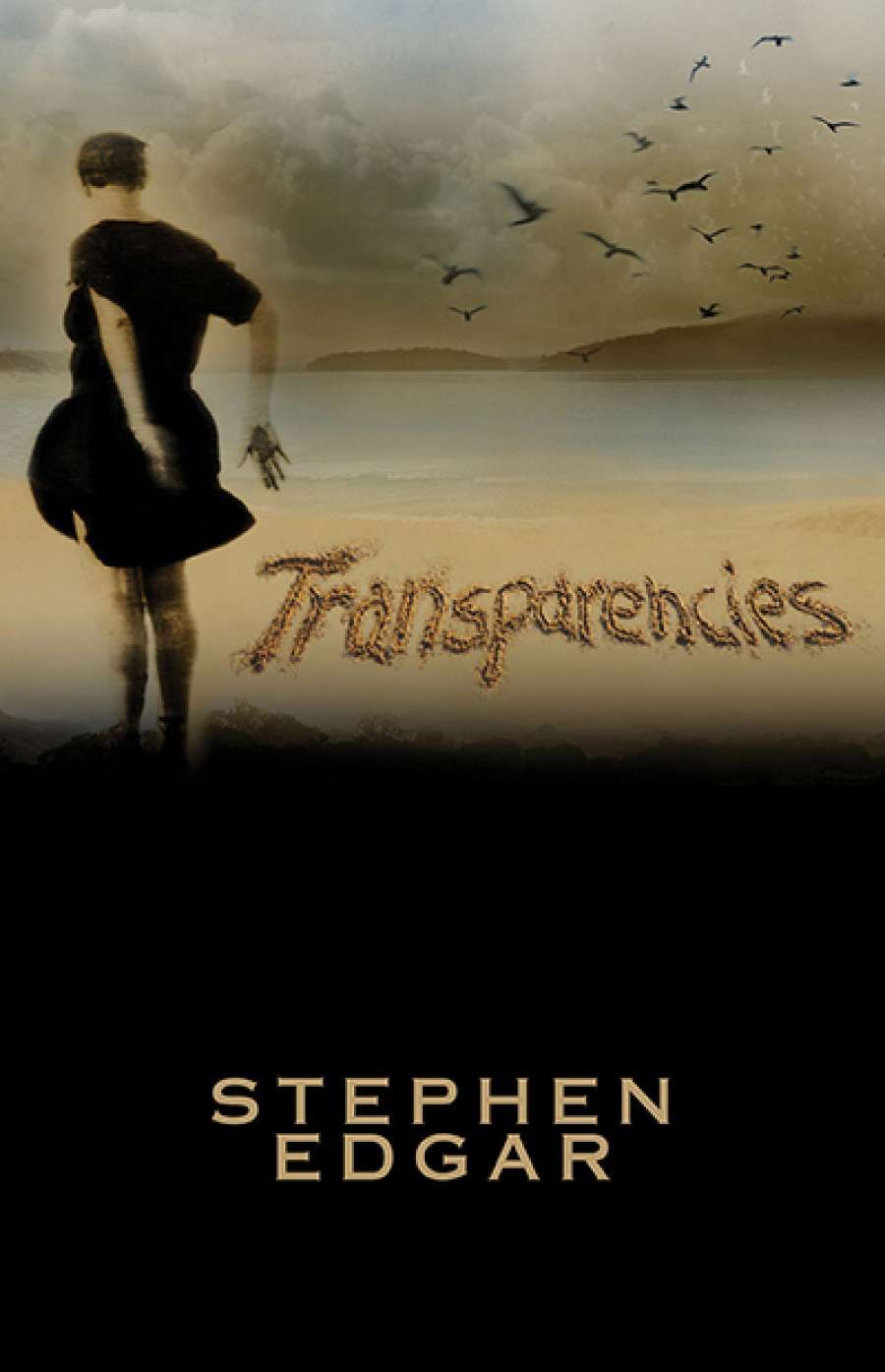

- Custom Article Title: Geoff Page reviews 'Transparencies' by Stephen Edgar

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

After Stephen Edgar’s nine collections of poetry, the last seven of which are distinguished by an extraordinary control over metre and rhyme, a reviewer feels bound to ask how this new book ...

- Book 1 Title: Transparencies

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Pepper, $24 pb, 89 pp, 9780648038702

‘Jupiter’, the first poem of the first section, is an introduction to the book’s twin preoccupations (and to Edgar’s poetic techniques for readers who may be unfamiliar with them). The first two lines are vintage Edgar: ‘The harbour’s idle undulations slew / And swill their slicks of glaze to make ...’ A businessman on a ferry is absorbed with calculations and ‘risk too intricate for even Lloyd’s / To cover’. Meanwhile, the poet and his reader merely ‘watch the slurs / Of gloss and shifting craquelure’, before both are reminded that ‘They say / It’s Jupiter’s / Vast mass that draws off, and may hurl our way, / A terminating hail of asteroids.’

That last sentence certainly puts things into perspective, not only for the businessman with his complex calculations, but also for the rest of us. The sardonic rhyme of ‘Lloyds’ and ‘asteroids’ on either end of the stanza is also a typical Edgar touch – as is the use of ‘craquelure’, a word many readers will need to look up, only to discover that, though metaphorical, the term is used accurately. It is characteristic too (but not universally the case) that ‘Jupiter’ is written in a complex stanzaic form of Edgar’s own making, with line lengths varying from dimeter through to pentameter. The device (along with a rhyme scheme to match) creates a sense of complex inevitability even while it also risks being a distraction.

It is notable, however, that Edgar’s best poems always end in a powerful image which tends to erase memories of difficulties experienced along the way and thus leaves us with an awareness of the poem as a resonant whole. ‘A terminating hail of asteroids’ is certainly an arresting last line.

Another poem of comparable impact is ‘Forest Doxology’. Here, Edgar takes advantage of zoological research by Jane Goodall and programs by filmmakers such as David Attenborough to present a disturbing parallel between chimpanzees and human apes. Like us, the chimpanzees murderously hunt in packs; like us, they can stop to admire a waterfall without quite knowing why. The paradox is that chimpanzees contrive to do both ‘Without the power of speech’. At the poem’s end, after the waterfall viewing, Edgar notes (with a wry nod to Wittgenstein) how: ‘At length they make their way, / Holding a picture memory replays, / Whereof they cannot speak.’

Stephen Edgar (photography by Vicki Skarratt)Among the most satisfying poems in Transparencies are those which evoke the poet’s mother’s final months and days. Here, in poems such as ‘Mother’s Day’, ‘On the Beach’, ‘The Sense of an Ending’, and ‘The Art of the Fugue’, we encounter the usual technical expertise, but, on these occasions, see it harnessed to more direct emotions. Edgar remembers, for instance, in ‘The Art of the Fugue’, how ‘Nurses, as ever, came and went. / Small groups of relatives stood round / Their proper beds and by a mute consent / Were mutually and thoughtfully ignored.’ It is these poems (and a number of comparable ones) that persist individually in the memory, like the best poems of, say, Philip Larkin or Robert Lowell, rather than being just a part of a more general impression of extreme accomplishment.

Stephen Edgar (photography by Vicki Skarratt)Among the most satisfying poems in Transparencies are those which evoke the poet’s mother’s final months and days. Here, in poems such as ‘Mother’s Day’, ‘On the Beach’, ‘The Sense of an Ending’, and ‘The Art of the Fugue’, we encounter the usual technical expertise, but, on these occasions, see it harnessed to more direct emotions. Edgar remembers, for instance, in ‘The Art of the Fugue’, how ‘Nurses, as ever, came and went. / Small groups of relatives stood round / Their proper beds and by a mute consent / Were mutually and thoughtfully ignored.’ It is these poems (and a number of comparable ones) that persist individually in the memory, like the best poems of, say, Philip Larkin or Robert Lowell, rather than being just a part of a more general impression of extreme accomplishment.

In Transparencies, as in other recent collections by Edgar, there are also a few poems which don’t rely on a strict rhyme scheme. It is interesting to ponder their relative effectiveness. Is Edgar letting himself off too easily here and ‘playing tennis without a net’, as Robert Frost argued free verse does? The truth is that Edgar’s verse is never ‘free’. The unrhymed poems still have strict stanza structures, adhere to an iambic metre and feature the same metaphorical density as the others.

‘The Returns’, for instance, is in tercets with a trimeter in the first line and pentameters in the second and third and with virtually no rhyme. It is about citizens returning to a city after being forced to flee by war. ‘The city is still there, / Of course – or rather, another city now, / Which occupies that name as it does the ground, // And people in whose mouths / A speech still recognizably the same / Sounds not quite right, like a fluent foreigner.’

In the few poems where this relative openness appears, the reader senses, with gratitude perhaps, that the poet has not made a prison for himself but is free to move into, and out of, strict form as suits his needs. Transparencies is well up to the standard that Edgar has, in the past twenty years or so, increasingly set for himself.

Comments powered by CComment