- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Journal

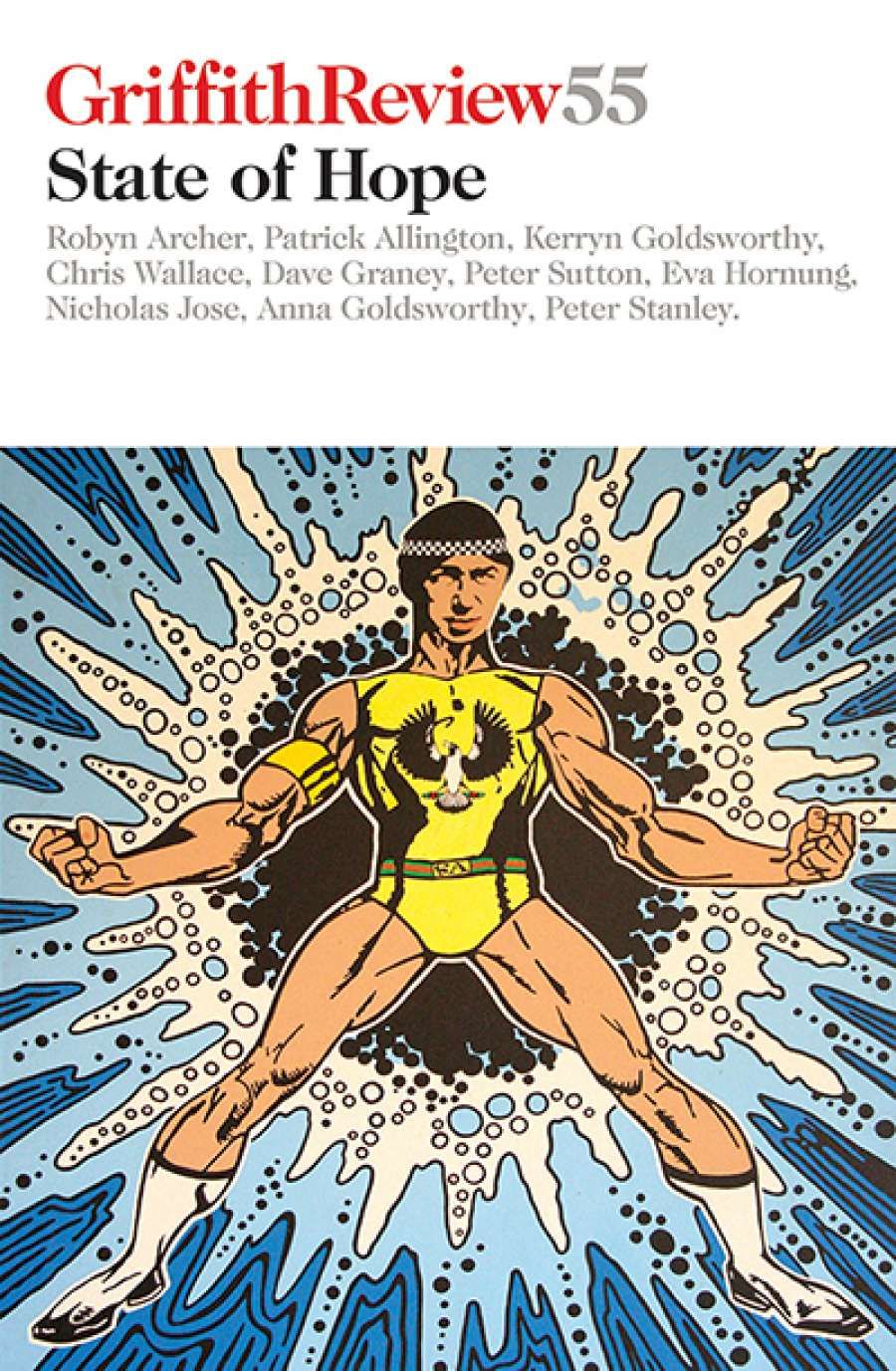

- Custom Article Title: Robert Crocker reviews 'Griffith Review 55: State of Hope' edited by Julianne Schultz and Patrick Allington

- Book 1 Title: Griffith Review 55

- Book 1 Subtitle: State of Hope

- Book 1 Biblio: Griffith University/Text Publishing, $27.99 pb, 306 pp, 9781925498295

So, what does make South Australia so different? Well, firstly, there is the story of South Australia’s colonial origins, which, by Australian standards, is unaccustomedly idealistic, certainly more than the usual story of a grab for land. As Julianne Schultz in her introduction points out, South Australia was founded by Reformers (with a capital R), idealistic gentlemen devoted not only to freedom of religious belief and political association, but to equality of opportunity, and even a fair and equal treatment of indigenous peoples, at a time when none of these things was valued elsewhere. This reforming spirit periodically erupts from South Australia into national politics, with the Nick Xenophon phenomenon being a useful example, summed up here in Dennis Atkins’s essay on the ‘radical centre’. This is good for the state, because it means those in Canberra who forget why this ‘radical centre’ exists, and why South Australia persists in embracing new things they don’t like, must at least look over the border occasionally and attend to our demands. Like their nineteenth-century forebears, it seems, South Australians prefer their centre-right pro-business party to embrace social issues more positively than their eastern neighbours, and Xenophon embodies this tradition.

Secondly, South Australia is not ‘a green and pleasant land’, except for a month or so in the winter. As the old saw goes, it is ‘the driest state in the driest continent’, having what my father used to refer to rather too kindly as an ‘ascetic climate’, cold and windy in the winter and often oppressively hot in the summer, with an erratic rainfall. This has created a history of many failed attempts to ‘make good’ on the land, which is evidenced not only by the smaller size of Adelaide compared to the other capitals, but, more tragically, by the ruined homesteads of those who once dared settle above the so-called Goyder’s Line to the north (named after an extraordinary South Australian). Apart from the shared Murray, there is no big river in the state, and no easily accessed source of water, apart from a few creeks in Adelaide itself. This creates natural constraints that everyone in South Australia feels sooner or later, but constraints that have probably inspired an unusual spirit of ingenuity and innovation.

Adelaide, North Terrace 1839, looking south-east (Wikimedia Commons)

Adelaide, North Terrace 1839, looking south-east (Wikimedia Commons)

Thirdly, as many of the essays in this collection suggest, including Robyn Archer’s charming memoir of growing up in Adelaide, it is the creativity and risk-taking of a handful of persistent South Australian individuals that have again and again come up with the goods. For example, the successful resurrection forty years ago of the state’s wine industry, now worth over $2 billion to the state’s economy, was not the result of politicians luring large companies with public largesse to start growing more grapes. As Max Allen’s perceptive essay on the more recent upsurge in quality winemaking in the Riverland shows, these things have a way of starting in the hearts and minds of a few brave individuals who are willing to ‘give it a go’, often against considerable odds, and typically against the advice of those who think they know best.

Finally, and closely related to this, South Australia has an unusually positive attitude towards the arts and culture, which persists despite the deadening hand of a reactionary conservatism that has progressively white-anted not only the legacy of Don Dunstan, but creativity, education, and science across the nation. As in the social sphere, Dunstan built upon a structure that had deep roots in South Australia. For example, Adelaide’s surviving art, design, and music schools are amongst the oldest in the nation, despite the state’s relatively small population and typically persistent lack of funds. Its artists, writers, dancers, musicians, and scientists have on many occasions achieved international fame, even if leaving Adelaide and South Australia was the price they had to pay, something else that again and again crops up in South Australia’s story.

Adelaide city centre today (photograph by Norman Hackenberg)

Adelaide city centre today (photograph by Norman Hackenberg)

As this rich and distinctive collection of essays and stories shows, despite its relative isolation, small population, entrenched social and economic problems, and troubling post-industrial malaise – nicely summarised in John Spoehr’s opening essay – South Australia is an unusual, extremely diverse, and persistently innovative sort of place. Like an annoying younger brother to Australia’s much larger and richer east coast states, the state persists in being a sort of living laboratory of creatively divergent endeavours that occasionally, and spectacularly, bear fruit. South Australia still has many reasons to be a ‘state of hope’.

Comments powered by CComment