- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

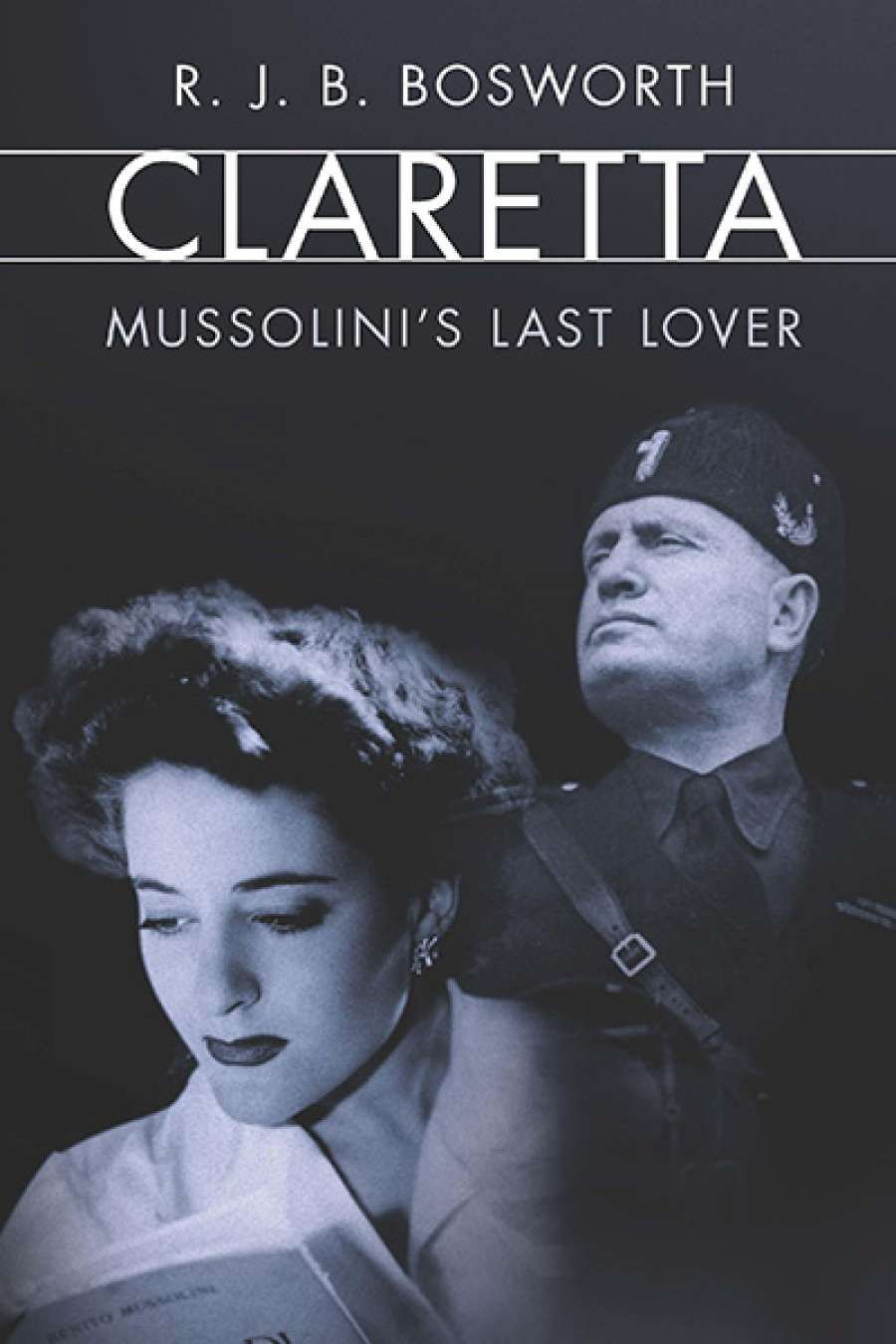

- Custom Article Title: Diana Glenn reviews 'Claretta: Mussolini’s last lover' by R.J.B. Bosworth

- Book 1 Title: Claretta

- Book 1 Subtitle: Mussolini’s last lover

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press, (Footprint) $39.99 hb, 312 pp, 9780300214277

The searing image of the lovers’ bloodied corpses hanging in public view in Milan’s Piazzale Loreto in 1945 is the starting point for a frank and intimate account that is interlaced with public and private events. From then on, all is on view as the author draws out the visceral and deeply personal aspects of Claretta’s involvement with Mussolini, recording both her highly charged declarations of lifelong devotion to, and worship of, her Duce, alongside details such as the pragmatic itemisation of their experience of sexual congress which she recorded in her diary with the word si (‘yes’), appropriately underlined for good measure. At the same time, Bosworth expertly draws on a multiplicity of sources in order to provide a comprehensive account of the love affair, the constant rivalries and jealousies occasioned by Mussolini’s other sexual exploits, the unrelenting exertions of his wife, Rachele, to destroy the Petacci alliance, the demands of children, legitimate and illegitimate, and myriad other entanglements (all closely monitored by the secret police) that contributed to the daily pressures of ‘a national boss who did not always have government business at the top of his agenda’. Amid this web of domestic strife and political power-mongering, the author spares no one in highlighting the supreme egoism of the Duce, the rampant publicity-seeking of the Petacci family, and the self-serving efforts of the Mussolini clan.

Bosworth first introduces his subject with allusions to the many artistic representations of ‘Ben and la Clara’ (as Ezra Pound termed them in his Pisan Cantos), in the form of poems, plays, a semi-documentary, film, and biographies. While he contends that with the passing of time ‘the world has largely forgotten Claretta’, this is not the case in Italy, where dark tourist sites and purported ghost sightings are part of the attraction that her memory continues to exert on the imagination of the Italian people: ‘Italy remembers’. In his narration of her story from her privileged upbringing in the Petacci family’s elegant dwellings to her final resting place in a mausoleum in Rome, the author traces sites of memory connected to Claretta’s life with a singular and unrelenting curiosity and flair. Regarded as ‘delicate’ by her parents, Claretta did not embark on secondary education, but her propensity for self-expression was strong. Her first recorded letter to the Duce at age fourteen is revealing of the adolescent worship that would later transform into an enduring love. However, as the author makes evident, the relationship between the younger woman and the older married man, who continued to engage sexually with numerous women during their time together, remained one of authoritarian and patronising control, even as her adolescent worship of him as a divine being transmogrified into a shared mutual passion. Even at the height of their affair, Claretta was subject to a continuous barrage of telephone monitoring and communication from the Duce: ‘On 3 January 1938 his tally of telephone calls reached thirteen (at 8.45, 10.45 and 11.30 a.m., and at 2.30, 3, 3.15, 4, 6, 6.15, 7, 8, 8.15 and 9.45 p.m.).’

Although Bosworth’s account is peppered with the tales of other diaries, such as the fate of the false Mussolini diaries, and the publications of ‘true’ accounts and histories by other family and party members, ultimately it is Claretta’s detailed recording of exchanges and actions that holds sway. In April 1945, as events were reaching a fearful climax, Claretta entrusted her personal records to her friend Countess Caterina Cervis, but eventually the papers were stored and catalogued in the archives in Rome. In fending off claims for their return by the Petacci family, the state’s lawyers deemed them ‘of genuine political import’ for their insights into the historic events of the day.

The body of Benito Mussolini (second to left) next to Claretta Petacci on display in Piazzale Loreto, 1945 (photograph by Vincenzo Carrese via Wikimedia Commons)

The body of Benito Mussolini (second to left) next to Claretta Petacci on display in Piazzale Loreto, 1945 (photograph by Vincenzo Carrese via Wikimedia Commons)

As the veneer of impregnability of Mussolini’s political persona began to crumble in the dying days of the regime, the ‘defeated old puppet dictator’ was forced to face his enemies and their retribution. The historical record is replete with analysis of Mussolini’s role and activity as a political figure. However, Claretta’s personal sacrifice and obsession continue to intrigue and mystify a postwar Italian public. As the author observes, despite strenuous efforts by many writers over the years to ignore her influence in Mussolini’s life, ‘Claretta’s impassioned and doughty “love” may have found a deeper place in Italian souls than anything that genuinely survives of Fascist ideology and practice’. Bosworth’s interweaving of intimate scenes with the exigencies of Mussolini’s role in the social and political events of the day gradually reveals Claretta’s role as a protagonist in popular history. The author employs his sources masterfully, and the volume is a fundamental contribution to our understanding of this relationship and provides a unique window into its curious workings.

Comments powered by CComment