- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

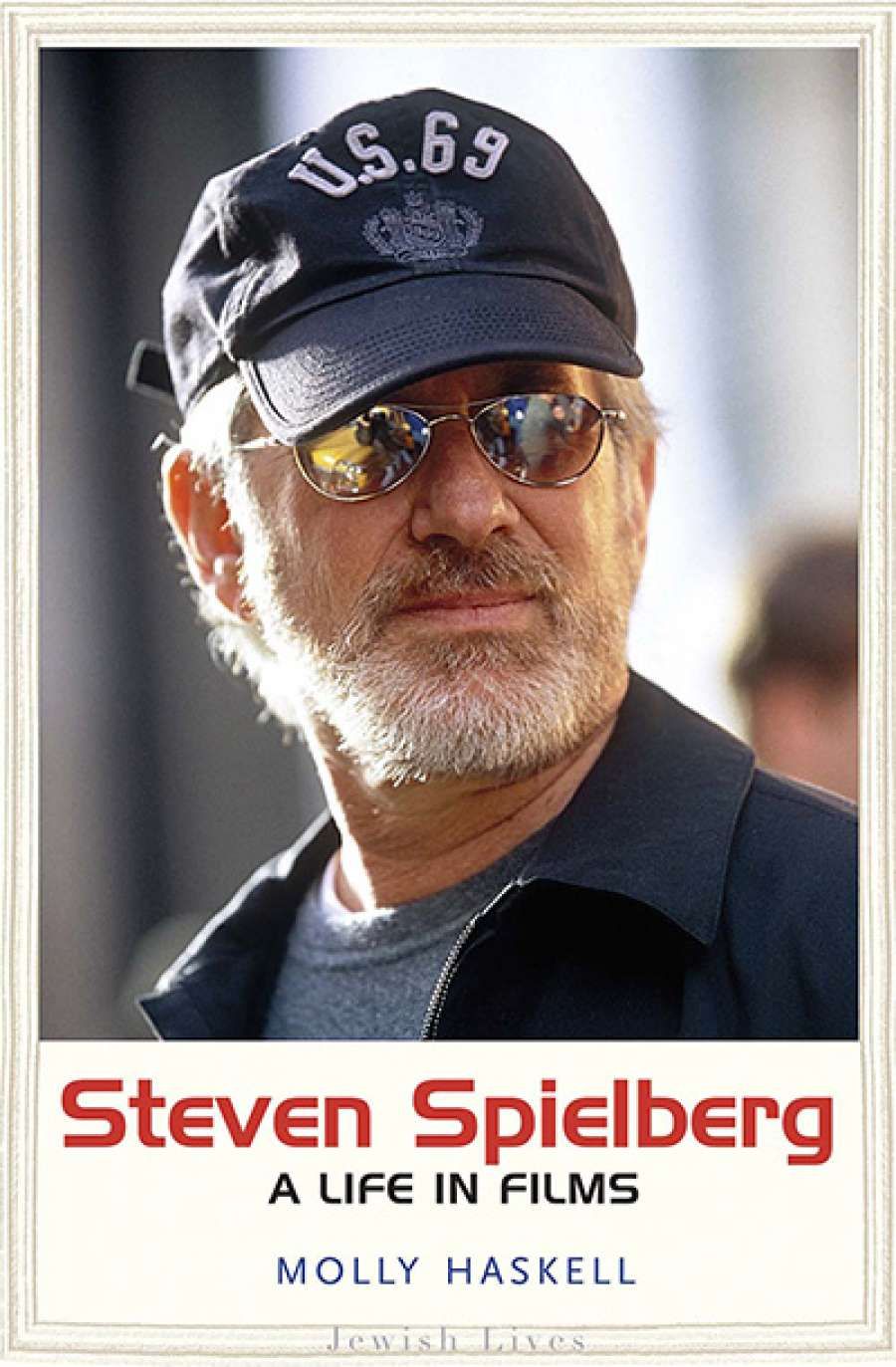

- Custom Article Title: Jake Wilson reviews 'Steven Spielberg: A life in films' by Molly Haskell

- Custom Highlight Text:

Steven Spielberg may be the most beloved filmmaker alive, but this has rarely stopped critics from patronising him. ‘Such moods as alienation and melancholia have no place in his films,’ ...

- Book 1 Title: Steven Spielberg

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life in films

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint) $36.99 hb, 248 pp, 9780300186932

If there is a grain of truth in Haskell’s assessment, there is also a hint of the condescension so often directed at Spielberg, and yet, in her disarming frankness and warmth, Haskell is the furthest thing from a snob. Six years older than her subject, and like him a product of American suburbia, she regards him with the mix of irritation and admiration a sister might feel for a gifted younger brother: it is this unresolved attitude which gives the book its liveliness and allows Haskell to view the films through fresh eyes.

Fresh up to a point, that is. There have been many books about Spielberg, most notably Joseph McBride’s astute, exhaustively researched biography, first published in 1997, with an expanded edition following in 2011. As her footnotes acknowledge, Haskell leans heavily on this near-definitive work, treating the mass of often contradictory testimony assembled by McBride as raw material to be boiled down to its essence; in doing so, she occasionally succumbs to the glibness which is the negative side of her rapid, vivid style.

Freudian concepts are a crucial part of Haskell’s critical tool-kit; she is unabashed in her efforts to psychoanalyse Spielberg from afar. For all his success, she portrays him as in some ways an eternal outsider, shaped by his Jewish sense of difference – the book was commissioned by Yale University Press as part of their ‘Jewish Lives’ series – and by the shock of his parents’ divorce. How much this really tells us is hard to say. No special knowledge of Spielberg the man is required to detect Oedipal subtext in Roy or E.T.’s yearning to board the mother ship; on the other hand, there have been plenty of nerdy Jewish boys from broken homes who did not turn their adolescent traumas into record-breaking box office hits.

Steven Spielberg, 1975 (photograph courtesy of Museum of Cinema, via Flickr)Some strain is visible in the effort to cover a long and prolific career in 200-odd pages: Haskell makes a handful of factual errors, and gives only a sketchy account of what Spielberg’s ‘technical mastery’ actually amounts to (for this, the formalist scholar Warren Buckland is a better guide). Still, she shows more understanding of Spielberg’s art than most of his devotees, pointing out that even his later ‘serious’ films have the exaggerated clarity of cartoons (a famous example is the girl in the red coat in Schindler’s List [1993], a speck of colour in a black-and-white world). Haskell sees, too, that his inhuman manipulation of emotion is essential to his artistic personality, and that his ruthlessly sentimental climaxes, with beams of pure light descending from on high, can be as alienating as they are ecstatic.

Steven Spielberg, 1975 (photograph courtesy of Museum of Cinema, via Flickr)Some strain is visible in the effort to cover a long and prolific career in 200-odd pages: Haskell makes a handful of factual errors, and gives only a sketchy account of what Spielberg’s ‘technical mastery’ actually amounts to (for this, the formalist scholar Warren Buckland is a better guide). Still, she shows more understanding of Spielberg’s art than most of his devotees, pointing out that even his later ‘serious’ films have the exaggerated clarity of cartoons (a famous example is the girl in the red coat in Schindler’s List [1993], a speck of colour in a black-and-white world). Haskell sees, too, that his inhuman manipulation of emotion is essential to his artistic personality, and that his ruthlessly sentimental climaxes, with beams of pure light descending from on high, can be as alienating as they are ecstatic.

Above all, she does justice to A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), for me not only Spielberg’s masterpiece but the greatest film to emerge from twenty-first-century Hollywood. Famously, the script was developed over many years by Stanley Kubrick, who proposed before his death that Spielberg replace him as director. The result is a unique hybrid, an adult fairy tale that for once confronts the implications of Spielberg’s obsession with innocence head-on. The protagonist is a robot boy (Haley Joel Osment) programmed to love his adopted mother (Frances O’Connor) for all eternity; separated from his sole object of desire, he pursues her as relentlessly as the shark in Jaws (1975).

Jude Law, Steven Spielberg, and Hayley Joel Osment on the set of A.I. Artificial Intelligence (photograph courtesy of Museum of Cinema, via Flickr)

Jude Law, Steven Spielberg, and Hayley Joel Osment on the set of A.I. Artificial Intelligence (photograph courtesy of Museum of Cinema, via Flickr)

Here is Oedipal longing with a vengeance. Mother and child are ultimately reunited after a fashion, and some critics have accused Spielberg of softening Kubrick’s original vision; but this claim, too, could not be further from the truth. Haskell knows better, aptly describing A.I.’s sublime ending as ‘poignantly and explicitly Proustian’. Tellingly, though, even she has trouble giving her subject full credit for knowing what he was up to – insisting that it was Kubrick, certainly not Spielberg, who had been reading Proust.

Comments powered by CComment