- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

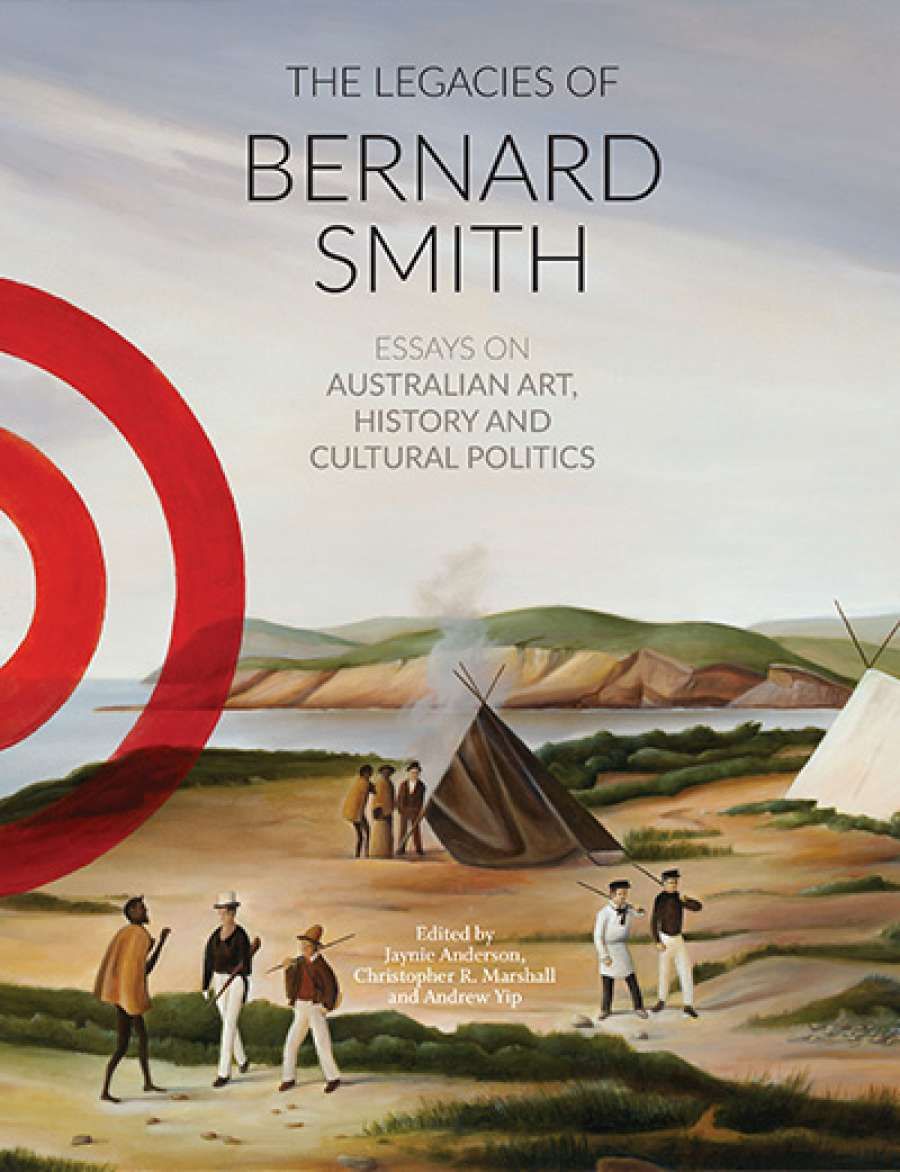

- Custom Article Title: Andrew Fuhrmann reviews 'The Legacies of Bernard Smith: Essays on Australian Art, history and cultural politics' edited by Jaynie Anderson, Christopher R. Marshall, and Andrew Yip

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: The Legacies of Bernard Smith

- Book 1 Subtitle: Essays on Australian Art, history and cultural politics

- Book 1 Biblio: Power Publications $39.99 pb, 372 pp, 9780994306432

It is still European Vision and the South Pacific (1960) that most intrigues. Smith’s classic study of the art of the European colonial period anticipated many of the issues around cross-cultural transmission and exchange that have dominated the humanities and social sciences for the last half a century. Kathleen Davidson’s forward-looking chapter draws on this landmark survey to suggest new lines of research into the place of photography in Imperial contexts. European Vision focuses on the ways in which the visual culture of Europe was influenced by encounters with the landscapes and peoples of the South Pacific and Australia. It is, therefore, a book about the impact of the periphery on the centre, and not the other way around. Paul Giles calls this Smith’s antipodean perspective, a critical strategy of inversion which Smith used throughout his career. Giles argues convincingly that Smith may one day be remembered chiefly as a cultural theorist, one who was sensitive to the different ways in which the global circulation of art and culture could be framed and reframed.

Today, however, Smith is best known as the first truly Australian art historian. The parochial problem of what makes someone truly Australian is one he often wrestled with. Catherine Speck critically examines his writings on expatriate artists and extracts a new and more tractable definition of Australian art. Andrew Sayers, meanwhile, reminds us of Smith’s foundational role in giving narrative shape to the development of Australia’s colonial artistic culture. Smith, for example, was the first to pay serious attention to the art of men like J.W. Lewin, and his assessments of their various contributions have proven surprisingly durable.

There is less praise for, and indeed less interest in tracing, possible legacies stemming from Smith’s last two books, Modernism’s History (1998) and The Formalesque (2007). Terry Smith laments that his former lecturer from the University of Melbourne refused to make room for critical theory in his frameworks of analysis. He argues that this ultimately crippled Smith’s attempt to understand Modernism in its relationship with Postmodernism. Terry Smith is also critical of Smith’s call for a return to the concept of period style and his coinage of a new term to replace Modernism, dismissing it as ‘smart-alecky anti-theory’. Robert Gaston – in a fine chapter on Smith’s years at the Warburg Institute – simply notes that the old man should have realised that style names are virtually immoveable. Certainly, the response to these two late works has been muted, but I tend to agree with Paul Giles that the shape of Bernard Smith’s legacy will not become clear until two generations have passed. I am not sure that we have heard the last of Smith’s ‘formalesque’, even if many now regard it as a quixotic folly.

Bernard Smith at his home in Fitzroy, Melbourne in 1987 (photograph by Alec Bolton)Smith was not simply a creature of the academy. We should remember that foundational books like Place, Taste and Tradition (1945) and Australian Painting (1962) were written for the widest possible readership. Smith was an acute historian, and he insisted on the highest standards of art-historical scholarship, but he was also conscious of the need to integrate the study of the history of art into the general life of the community. On this theme, Steven Miller offers useful details about the touring exhibitions which Smith organised at the National Art Gallery of New South Wales between 1944 and 1948, and Joanna Mendelssohn highlights the way in which Smith encouraged universities, galleries, and art museums to recognise their interdependence and to work together to raise the level of arts discourse.

Bernard Smith at his home in Fitzroy, Melbourne in 1987 (photograph by Alec Bolton)Smith was not simply a creature of the academy. We should remember that foundational books like Place, Taste and Tradition (1945) and Australian Painting (1962) were written for the widest possible readership. Smith was an acute historian, and he insisted on the highest standards of art-historical scholarship, but he was also conscious of the need to integrate the study of the history of art into the general life of the community. On this theme, Steven Miller offers useful details about the touring exhibitions which Smith organised at the National Art Gallery of New South Wales between 1944 and 1948, and Joanna Mendelssohn highlights the way in which Smith encouraged universities, galleries, and art museums to recognise their interdependence and to work together to raise the level of arts discourse.

In The Legacies of Bernard Smith, you will also find chapters reflecting on his time as a grassroots activist in the Sydney suburb of Glebe, as a collector who believed in a common responsibility to support the arts by purchasing new work, and as a public intellectual facing up to the consequences of colonial violence.

The collection sometimes seems a bit eclectic, but could it be otherwise? And if the chorus of Smith’s admirers and occasional adversaries gathered here tends to dwell on the individual man rather than his influence on others, it is nonetheless a generous tribute.

Comments powered by CComment