- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Inaudible Cries

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On the afternoon of Tuesday 23 December 1958, all work in the remote South Australian coastal towns of Thevenard and Ceduna came to a halt for the funeral of nine-year-old Mary Olive Hattam, who on the previous Saturday afternoon had been violently raped and then bashed to death in a little cave on the beach between the two towns. On the morning of her funeral, a 27-year-old Arrernte man called Rupert Max Stuart had been formally charged with her murder: he had arrived in Ceduna with a small travelling funfair on the night before her death. He spent Christmas Day in Adelaide Gaol, penniless, illiterate and terrified. How the Hattam family spent Christmas Day can scarcely be imagined.

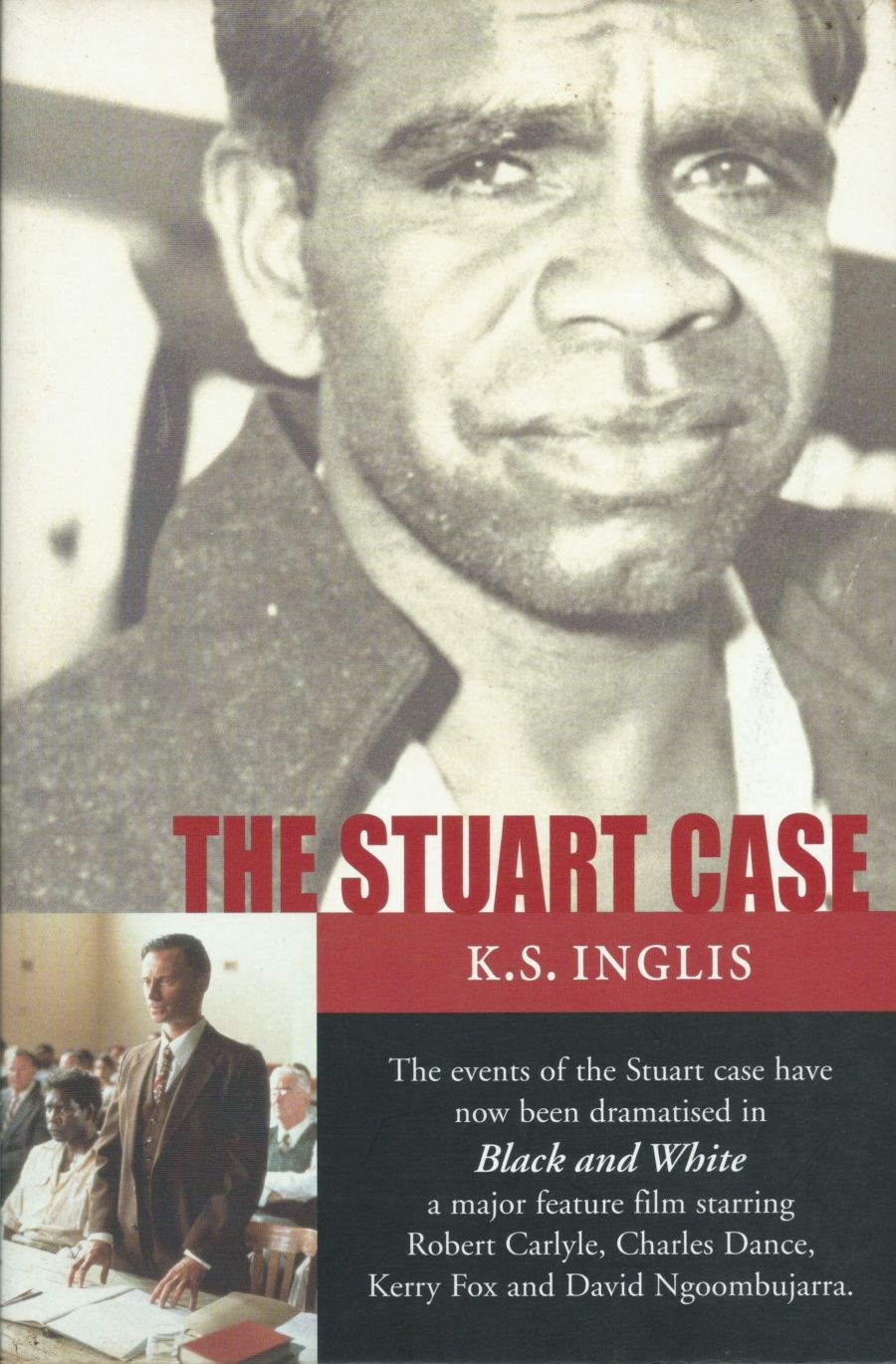

- Book 1 Title: The Stuart Case

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $27.95 pb, 404 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Mary Hattam’s death sparked one of the bitterest legal controversies in Australia’s history. Stuart’s arrest, trial, conviction and death sentence had repercussions – political, legal, ideological – that went on for decades. And when Adelaide’s Beaumont children disappeared from a suburban beach just over seven years later, the fate of Mary Hattam was in the back of every South Australian parent’s mind.

Ken Inglis was first drawn into the Stuart case in June 1959 when his wife Judy, an anthropologist, was invited to a meeting involving two of Stuart’s most staunch defenders, the Adelaide linguist and anthropologist T.G.H. Strehlow and a Catholic priest called Father Tom Dixon. Strehlow and Dixon both spoke Arrernte and so were able to communicate fluently with Stuart, and it was on this basis that both had become convinced of his innocence. By this time, Stuart had already been granted three stays of execution; there were to be another four. The meeting addressed by Dixon and Strehlow, held on 27 June at the home of Dr Charles Duguid – president of the Aborigines’ Advancement League – and attended by about fifty people, including representatives of the church, the law, the Aboriginal cause and the movement for the abolition of capital punishment, resulted in an organised campaign to save Stuart from the gallows. On the other side, led by the Crown Solicitor Roderick Chamberlain QC and the entrenched Liberal Party premier, Sir Thomas Playford, the conservative state government and the Adelaide Establishment squared off against this heterogeneous opposition and hardened in its determination that Stuart would hang.

The three respites already granted – Stuart was originally sentenced to be executed on 22 May – had followed various appeals made by his lawyers, David O’Sullivan and Helen Devaney. Thus far, it was only the resistance of these two that had saved him; from this point onwards, support for him gathered momentum thanks to the advocacy of Ted Strehlow and of Tom Dixon, who enlisted the support of Adelaide’s afternoon daily paper, The News, in his successful quest for the new evidence that led to a Royal Commission and thence to the commutation of the death sentence on 5 October. The paper’s editor, Rohan Rivett, had taken up the cause, as had its proprietor, the young Rupert Murdoch; in the wake of Stuart’s imprisonment, and at the instigation of the premier, Rivett and News Ltd were tried in the Supreme Court on a charge of seditious libel arising from an inflammatory headline. (Penalty: death. Verdict: not guilty.)

Inglis, in 1959, was a young academic historian moon-lighting for the fortnightly Sydney journal Nation; his first piece on the Stuart case was published on 18 July. By the time a Royal Commission inquiring into the case was announced, less than two weeks later, Inglis had ‘decided to write a book on the case, whatever its outcome’.

This new edition of The Stuart Case, first published in 1961, contains the original (and unaltered) text, plus Inglis’s eighty-page addition, headed ‘Epilogue 1959-2002’, and a chronology of the case and of Stuart’s life since. Over the last four decades of the twentieth century – most of which he spent in Adelaide’s Yatala Labour Prison – the so-called ‘half-caste’ with the drinking problem, the criminal record and the limited command of English, convicted in 1959 of rape and murder, was transformed into a senior and respected Arrernteman, a literate and charming advocate for his people who was elected in 1998 to the Chair of the Central Land Council.

Stuart learned to read and write in prison, and it may have done much more for him even than that. Inglis speculates not only that Stuart – a tribal initiate from childhood – was sustained and kept sane in prison by his knowledge of Arrernte lore and law, ‘remembered stories, liturgy and poetry’, but that his tribal knowledge was actually preserved by his incarceration, ‘locking him away from a Westernising culture which might have eroded his memory of the law ... It might even be said that Yatala kept Rupert Max Stuart sober and alive’.

This new edition of The Stuart Case was published around the same time that Black and White, the movie dramatisation of the case, was released in 2002; there was talk in South Australia of the possibility that an appeal might be launched to have Stuart’s conviction reviewed and overturned by way of drawing a line, within his lifetime, under the process of survival and rehabilitation.

Yet almost nothing about the Stuart case was or is clearcut – the movie title is intentionally ironic - and not all of those who worked to save Stuart’s life were convinced of his innocence: one of his main legal defenders, Jack Shand QC, thought him ‘probably guilty’, as did the young Labor MP Don Dunstan and the even younger historian Inglis. The Inglis of 2002 reflects that ‘My own estimate of probabilities remains pretty much as it was in 1961 ... I thought the case warranted the Scottish verdict "not proven’", and cites the argument of journalist Evan Whitton in support of a non-adversarial judicial system: in France, says Whitton, ‘Stuart would have been questioned by a judge whose task was "the manifestation of the truth", not by a Chamberlain determined to win’.

Inglis patiently pieces together the complexities of the Stuart case into a story that remains lucid and gripping, even when the legal wrangling becomes Dickensian. Reading this book over the summer of 2002–3, I’m struck – as a woman whose childhood was spent playing on South Australian beaches, four years younger than Mary Hattam and three years older than Jane Beaumont – by the way this case turns into a welter of power struggles among various white men; as the battles rage in court, in Parliament and in the offices of Adelaide’s two bitterly opposed newspapers, Max Stuart and Mary Hattam can barely be seen for dust. One man was moved to write to The News: ‘Out of the wild Jungle of law. politics. journalism, and religion, let us hear the almost inaudible cry of Mary Olive Hattam.’

The Epilogue ties up some loose ends and traces the later lives of key players in the drama. It seems even more lucid than the original text, but at the same time it has a hypnotic, poetic quality and it gathers momentum as it goes along, culminating in an account of the conversation with Stuart in 2002 that left Inglis’s ‘probably guilty’ conclusion intact but sharpened his sense of Stuart as a survivor:

Having escaped the noose against the longest of odds in 1959 he has outlived all the agents of the state that condemned and punished him, all his lawyers and all his champions except the other Rupert ... If he is innocent, his story is about a man who was the helpless victim of the legal system and the racist culture which it embodied, who endured a terrible injustice and then transcended the fate to which he had been condemned. If he is guilty, his rehabilitation, his psychic survival as an intact and apparently serene personality, is even more remarkable.

In 2002, as in 1959, Inglis’s main concern is not to apportion guilt but rather to get as close as possible to the various truths of the matter, and also to sketch the several big pictures brought into juxtaposition by the Stuart case and its aftermath.

And the book reveals in Inglis a quality that he shares with some of the other people – Rivett, Dixon, Dunstan – who come out of this story well: that he is more interested in understanding conflict than in causing it, waging it, or winning it. Nor does he forget where this particular conflict began; he ends the Epilogue, as he did the original text. with a reminder of the story’s epicentre: the cemetery at Ceduna, where the entrance gate bears the initials ‘M.H.’.

Comments powered by CComment