- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Oral Quarrel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What is the significance of these stories told by apparently unremarkable people? One thread lies in recording times not quite past, but still enduring amidst vast changes. Their common quality is stoicism, an ability to keep going, in the face of monumental shifts, not just the technological ones that we have all faced in the last century, but huge transformations to cultural life.

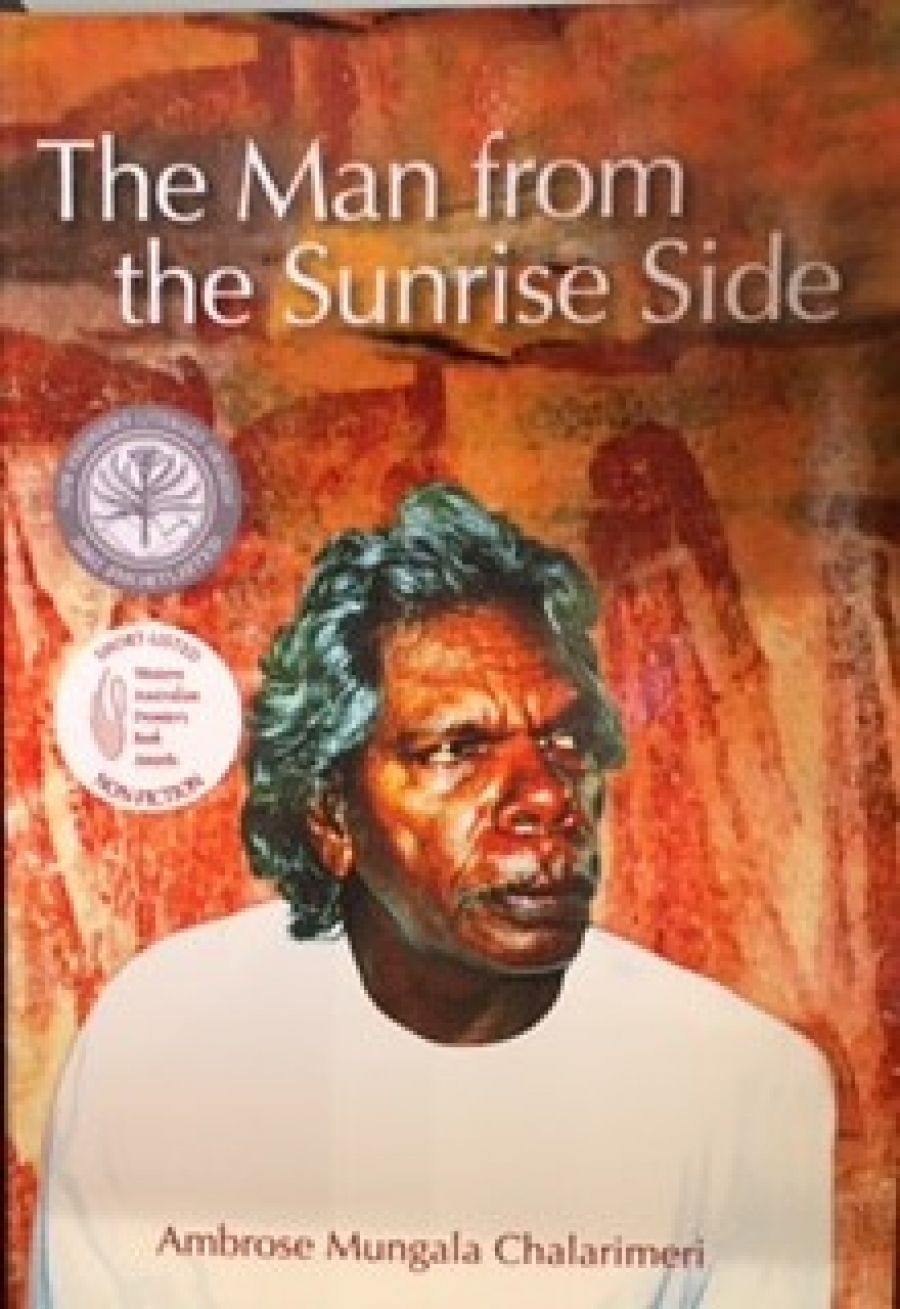

- Book 1 Title: The Man From the Sunrise Side

- Book 1 Biblio: Magabala, $2L95pb. 226pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: The Mish

- Book 2 Biblio: UQP, $19.95pb, 70pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Under a Bilari Tree I Born

- Book 3 Biblio: FACP, $24.95pb. 233pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

There are great differences between these three lives, not least because they stretch from the Kimberley and Pilbara in Western Australia to the south-east of Australia around western Victoria. Tony Staley, chair of the National Museum, recently said: ‘I think the museum needs to make clear what sort of history it is relying on – oral tradition or historical fact.’ What does that make these stories? Since they are written down, I suppose they’re historical fact. Their authors largely don’t wear armbands, and express complexities often missing from ideological debates.

The Man from the Sunrise Side has a similar setting to Kim Scott’s fictional Karnama in his novel True Country. It is worth reading the two as complements. In Scott’s novel, the mission that has ‘held things together’ has lost its sway, and the consequences are not pretty. Ambrose Mungala Chalarimeri, however, takes us back to World War II when the mission was in full swing.

We didn’t really know much what bin happen outside the mission, how the whole country was getting full of kartiya [whites]. That there’s a big government now, telling people what to do. We didn’t know what government is. We only knew the little place we bin grown up; we didn’t know about anything outside like town, city, buses, trains.

Chalarimeri evokes the highly regimented mission life. As a relatively good boy, he ‘only got hit with the strap or the cane on the hands’. Others were flogged, publicly. Clearly, when self-government came to Kalumburu, no one was prepared for it. Ambrose had already left to find work, though he returns from time to time; he realises that, in a practical sense, his future is elsewhere, in spite of his ties to his country.

The illustrations in this well-produced book include some colour photographs of the much-disputed ancient Guyon Guyon (Bradshaw) rock paintings at Oomarri, and some wonderful black-and-white images, including a tall, gawky young Ambrose assisting at Mass in full liturgical gear. The cultural chasms are huge. What is remarkable is Chalarimeri’s ability to make sense of it all, to be in turn critical, nostalgic and realistic. His account of learning the perils of buying on credit is hardboiled and without rancour.

Chalarimeri ranges widely through traditional stories and cultural matters from his own Kwini country. He works and travels across the Kimberley. Among many stories is a good-humoured account of the Turkey Creek wine festival, an attempt to bribe the locals to vote Liberal with a drum of wine. Ernie Bridge won anyway, for Labor. But, as Chalarimeri observes: ‘Politicians always look good when they come, I myself can’t tell the difference. They fly in and out, don’t say nothing much, they only come to see the place and enjoy the journey. That money for the flight is wasted.’

Just as wide-ranging across culture and history is Alice Bilari Smith’s Under a Bilari Tree I Born, about her move from station life to a semi-urban existence in the west Pilbara. Born in 1928, on Rocklea Station, she had spent all her life in the Pilbara working on various stations before moving to Roeboume. To say that her kind of bush life – contract fencing – was hard work is to sell it short. Yet, Smith says: ‘It was easier on the station than town life. Town life you got to look after everything … When you got a house you got to do the cleaning the house first, then you think about start cooking then.’

Paying bills and rent, and voting, are all mere inconveniences compared with the tough business of survival on the land. It is difficult to imagine the grind of digging holes, placing posts and stringing wire, hunting for food then preparing it, in addition to having a baby. Much worse are the grog and the drug-taking in the community, against which Smith struggles. As well as her own nine children, she has fostered another fifteen.

Loreen Brehaut. one of the collaborators on this book, also worked with Florence Corrigan on her Miles of Post and Wire. I assume this is the same Mrs Corrigan who makes a fleeting appearance in Under a Bilari Tree I Born. Both women, Alice and Flo, had amazing working lives, spent mostly fencing, while raising large families in the bush. They are quite precise in their assessments of the varying qualities of the station owners, shopkeepers and coppers with whom they have to deal. Worth quoting is an aside from Alice Smith about one more famous Australian: ‘Lang Hancock used to never help Aborigine people; he was greedy for money.’ But I suppose that’s an example of oral tradition

Robert Lowe is from the well-known Clarke family, and his story, The Mish, centres around the Framlingham Aboriginal Mission in Victoria. By the time Robert was born, in 1947, the Mission had been officially closed for nearly sixty years. His story is about the people and families left behind on the Mish, who were part of Robert Lowe’s early life. Nearby Warrnambool was full of threats, so the world of the Mish was a refuge and a great place for kids to grow up. Hardly flash, but loving. What Lowe does with great success is re-create this enclave almost as if no outside world exists, and while it does not, he is safe. Sliding towards the creek on loose pieces of tin, fishing, hunting and eel-catching, wagging school: it seems an idyllic existence.

When he ventures away from the Mish, he becomes a successful footballer, raises a family and works in a variety of jobs. It’s not all beer and skittles and, though he does not dwell on the difficulties, Lowe mentions family disagreements, money worries and so on. But he is rightly proud of his 399 games of footy over the years and his work to get troubled kids back on track.

There is a brief glimpse of an ‘armband’. Lowe cites family stories about ‘the Sunday shoots – massacres of Aborigines by whitefellas on horseback’ near Warrnambool. He adds the qualification that it ‘has never been told by the whitefella and never will’. How right he is. It is, after all, only oral tradition, not historical fact. Though one does wonder why his mother, grandmother and great-grandmother made it all up and passed it on.

The three publishers deserve credit for making these stories available and having obviously taken great care with their editing and production. All three books exude a gentle energy; they are not pushy, brash or self-important. Lowe demonstrates this at the end of The Mish:

There’s one place we stop at, near Wentworth, and I feel as if I’ve been there before. It feels so homely, warm and peaceful. When we arrive the old people that once lived around that area let me know if we are safe to stay or not. When it’s time to leave I always thank them.

Would that we could all say the same.

Comments powered by CComment