- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The unfinishable

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

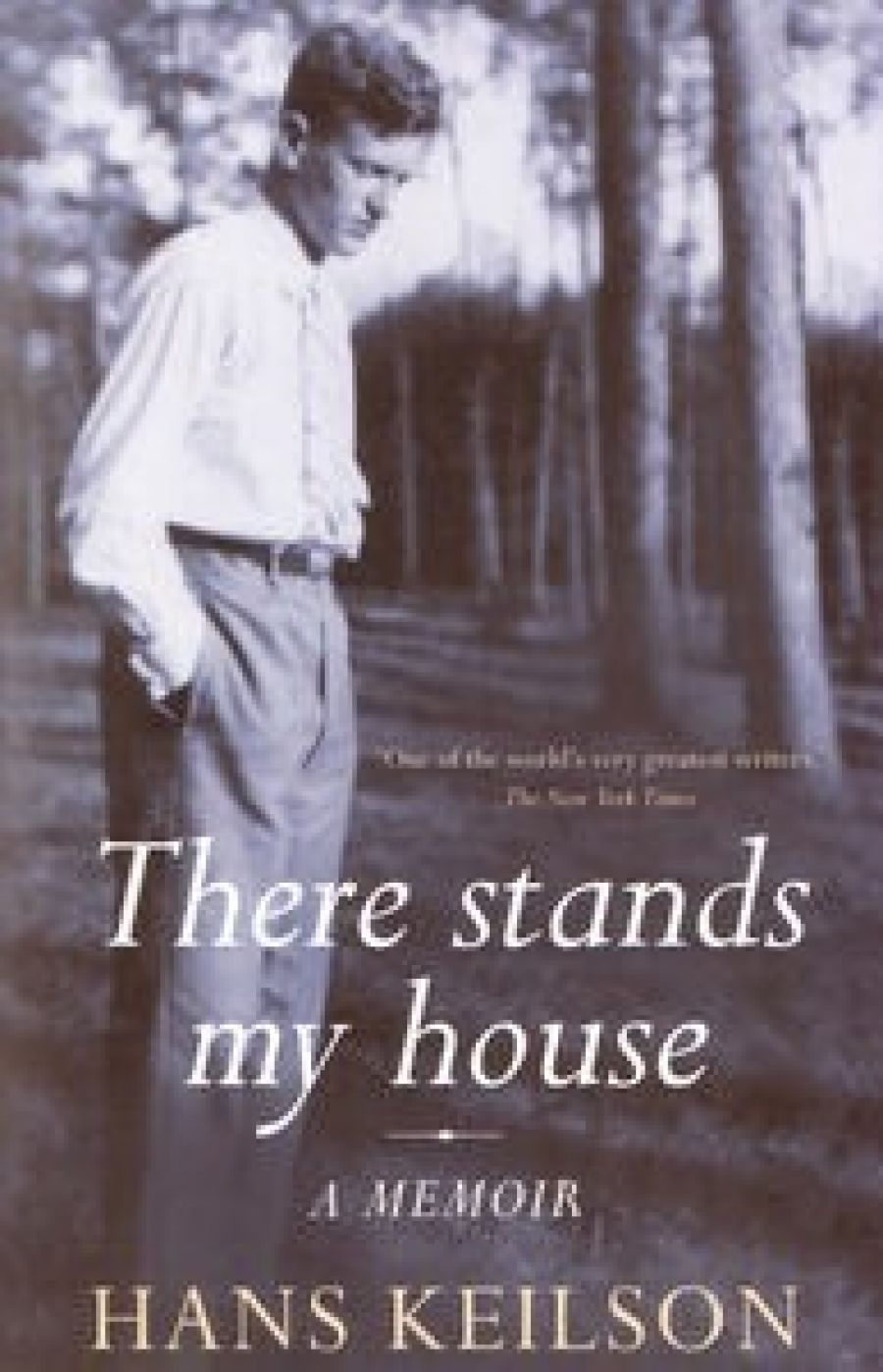

For the unacquainted reader, a few facts about Hans Keilson, author of There Stands My House: A Memoir. A German Jew, Keilson fled the Nazis for the Netherlands in 1936. After the war he wrote and published two novels, Comedy in a Minor Key (1947) and The Death of the Adversary (1959), both of which were unread for decades but which have now been rediscovered and received as masterpieces in the Anglophone world. Keilson also had a long, accomplished career as a psychiatrist, specialising in the treatment of children traumatised by war. He died on 31 May 2011 at the age of 101. Scribe is the first house to publish his memoir in English.

- Book 1 Title: There Stands My House

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $24.95 pb, 128 pp

There Stands My House, which, unlike the novels, was composed recently, comes with a Translator’s Note by Elena Lappin, an Editor’s Note by Heinrich Detering, and ‘One Hundred Years’,a conversation between Detering and the author. These documents, which touch upon many of his medical and literary achievements, comprise something of an oblique portrait of Hans Keilson, the unobtrusive polymath.

There Stands My House is a slight work in comparison with the novels. The narrative moves from his childhood in Brandenburg to his days as a student in Berlin, describing his life as an exile, his endless sadness at the death of his parents in Birkenau, and his resolve to dedicate his life to helping those orphaned during the Holocaust. Keilson describes the tension of growing up in an increasingly anti-Semitic Germany and the sadness of losing one’s homeland. The prose is uncluttered, his reflections marked by an idiosyncratic sense of detail. Of the letters his father sent him from Berlin after he went into hiding, Keilson recalls ‘his clear, strong handwriting on the small-price labels written with glossy paint when he redecorated his two shop windows’. If this were a traditional work of memoir, which sought only to provide a detailed, chronological catalogue of the events of a life (or put more simply, if Keilson were a lesser writer), it would be the life itself that makes this book incredible – but this is not the case.

The shape of the text, as explained in the Editor’s Note, is deliberately fragmentary. As Detering puts it: ‘the text appeared to the author himself as not only incomplete, but also unfinishable.’ Everything about Keilson’s writing is natural and unmannered. This hesitancy to impose a literary form onto his life is part of what makes his testimony so rare: his awareness of the deceptive power words can have, the ability of prose to make banal a horror that – unless one was there, so to speak – is unknowable (not that Keilson himself would be so blunt). Instead, Keilson, with the clinical mind of a psychiatrist, interrogates his own method and the reliability of his words: ‘Personality changes affect the nature of memory. This sentence […] should introduce every memoir, and especially the kind of account I plan to write here.’ He adds later: ‘The picture will not be composed solely of chronological events, but rather of inner connections between thoughts and feelings.’ On almost every page he seems to be searching his memory, observing some strict though unstated criteria that he has set for himself, determined to mention only what is true and, as he says later, what seems relevant. His project, in his own words, is an attempt ‘to define the internal as much as the external situation of the place where I lived at the time’.

The first of the other documents presented here, Lappin’s short note, is an account of meeting and corresponding with Keilson long before the republication of his novels (Lappin originally made contact because she was seeking a psychiatrist who specialised in the trauma suffered by children during World War II). Lappin quotes Keilson, who was responding to a question regarding the possibility of someone forging a memoir describing life in the concentration camps as a child. The words he offers go some way toward explaining the mysterious power of his writing:

The Shoah as a source of inspiration? Destruction, sadness as a source of literary, scientific creativity and work? De Sade, eros, genital sexuality as a stimulus? Why not. In this sense, literature is amoral. We will have to learn to accept and respect this approach. Thomas Mann had already done so in Tonio Kroger and Death in Venice.

These sentences (which seem to hesitate, diffidently introducing an assertion via self-interrogation) can be read as the bare bones of Keilson’s compassionate intelligence, which, only years after his own survival, he trained on the Holocaust. This intelligence – which defines There Stands My House, just as it defines his novels – is the secret of Keilson’s writing (though he would probably have rejected the suggestion that his writing contained secrets, marked as it is by clarity and openness): the total reluctance to judge, or condemn. That someone might exploit the stories of the Holocaust, which Keilson himself endured but which claimed his parents’ lives, did not shock him. Instead, it provoked acceptance and respect, and brought forth a radical and inclusive vision of literature. The quiet thoughtfulness of this book is luminous.

Comments powered by CComment