- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

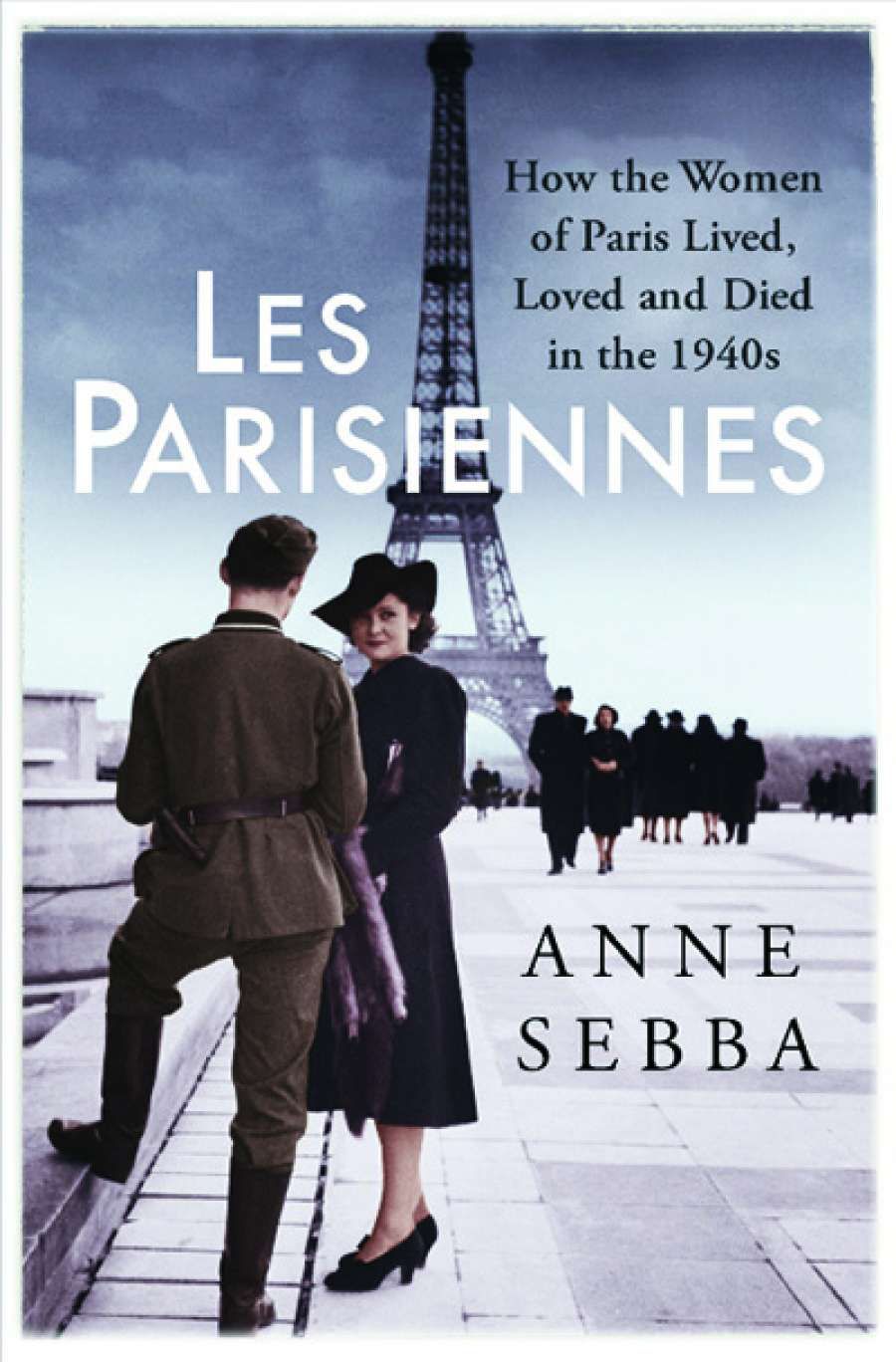

- Custom Article Title: Colin Nettelbeck reviews 'Les Parisiennes: How the women of Paris lived, loved, and died in the 1940s' by Anne Sebba

- Book 1 Title: Les Parisiennes

- Book 1 Subtitle: How the women of Paris lived, loved, and died in the 1940s

- Book 1 Biblio: Weidenfeld & Nicolson $32.99 pb, 480 pp, 9781474601733

Sebba has the broad lines of the history right, but on the level of detail there are many flaws that raise questions about the solidity of her knowledge. This is particularly obvious in her inadequately informed portrayal of the French cinema industry during the Occupation; and her account of the French government in exile in Sigmaringen is quite misleading. She also, perhaps even more tellingly, given her emphasis on Jewish matters throughout the book, quotes significantly contradictory figures on the percentage of Jews deported from France (pages 197 and 383). Nonetheless, the fiendishly complicated life of the French under Nazi rule is generally well-illustrated and documented: the tangled tensions between the occupied and ‘free’ zones; the attempts to promote, through salons, the arts and fashion, a sense of life going on as usual, despite a climate permeated by fear, material need, and denunciation; the ambiguities of relationships between French women and German soldiers; the shameful French State complicity in the ever-tightening web of humiliation, spoliation, and destruction of France’s Jewish community; the underworld of black marketeers and Gestapo-helpers; the conflicts among different movements of the Resistance; the unassuming courage and sacrifice of many ordinary French people, especially women. Her evocation of the postwar period is patchy, but contains some important insights into why this period remains so fraught in the collective memory of the French: the rush and brutality of the purges, for example, and the encounter between deportees returning to Paris and a resident public unwilling or unable to hear or comprehend the death camp experiences.

Although not the first to draw attention to the ways in which, under Charles de Gaulle and afterwards, women were elided from the early histories of the Occupation years, particularly in respect to the Resistance, Sebba has drawn together an impressive cast of female figures. It is a significant achievement of her book to remind her readers that all these people belonged to the same world as de Gaulle, Pétain, Jean Moulin, Pierre Laval, and all the other canonical heroes and villains of the time. Some are famous, like Chanel, Piaf, Arletty, Némirovsky and Geneviève de Gaulle. Others, such as Corinne Luchaire, Suzanne Belperron, Violette Morris, Odette Fabius, and Rose Valland, may be less known to readers, but Sebba makes a strong case that their lives should not be forgotten.

Corinne Luchaire and Camillo Pilotto in a scene from Abbandono, 1940

Corinne Luchaire and Camillo Pilotto in a scene from Abbandono, 1940

(Mario Mattoli via Wikimedia Commons)

All these stories make for a breathless narrative, which often becomes less compelling through its failure to discriminate between hearsay and historical evidence, and between the important and the trivial. Insatiable curiosity about the minutiae of people’s lives does not necessarily lead to historical accuracy or well-balanced books, and Sebba does not help her claim to offer greater understanding by giving more space to Duff Cooper’s Paris dalliances than to the Marshall Plan.

For me, the most engaging and original section of the book is the epilogue, where Sebba reflects on the obstacles to making moral judgements about the period. She notes things still passed over in silence, such as Jewish families whose survival depended on their economic or industrial contributions to the German war effort. She notes the unintended injustice of the French legal distinction between ‘resister’ and ‘victim’ deportees: the latter, mostly Jewish, receiving less respect and less compensation. She notes the nobility of Geneviève de Gaulle’s postwar work with Father Joseph Wresinski in founding the ‘Fourth World’ movement to eradicate world poverty. All this takes her, and her readers, beyond the learned history and the gossip, into a meditation on the deep ambivalences of human nature and the terrible, long shadows of war.

Comments powered by CComment