- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Publisher of the Month

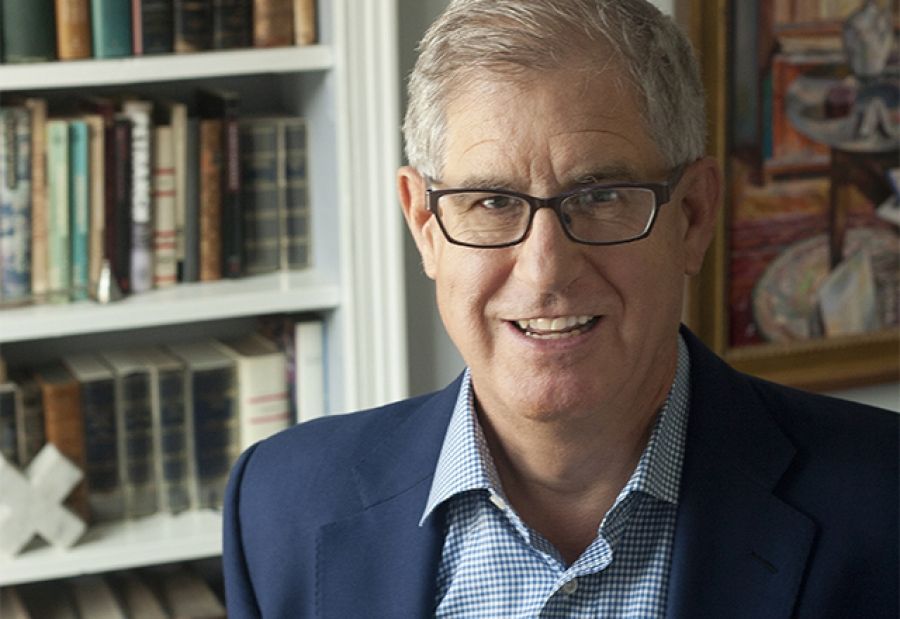

- Custom Article Title: Jonathan Galassi is Publisher of the Month

- Review Article: No

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

After university I knew I didn’t want to do deconstruction; I wanted to be involved with contemporary writing, so I looked for an editorial job and eventually found one, in Boston, which was no longer the Athens of America, in 1973.

Name the first book you ever published.

I think it was A Boston Picture Book (1974), by the artist Barbara Westman. I loved her and loved the whole process!

Do you ever edit the books you commission?

Very often, though I sometimes also have a collaborator backing me up.

How many titles do you publish each year?

Twenty-plus.

What are the main qualities you look for in a new author?

Originality of expression, freshness, and coherency of voice.

In your dealings with authors, what is the greatest pleasure – and challenge?

Pleasure: minute engagement with the author’s text, and hence with his/her mind. Challenge: winning the author’s trust, so that she/he feels we’re in this together.

Do you write yourself? If so, has it informed your work as a publisher?

Yes, I’ve written poetry, translated Italian poetry, and am now writing fiction. The interplay with what I do as a publisher is constant, but I might say my work as a publisher has informed my writing more than vice versa, though I’ve never felt impinged on by others.

Who are the editors/publishers you most admire?

There are a lot. Here are a bunch, in no particular order: Horace Liveright, Alfred Knopf, T.S. Eliot, Edward Garnett, John Murray, Pat Covici, Malcolm Cowley, Bennett Cerf, Donald Klopfer, Leonard and Virginia Woolf, James Laughlin, Valentino Bompiani, Giulio Einaudi, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, Gaston Gallimard, Hamish Hamilton, Norah Smallwood, Carmen Callil, Siegfried Unseld, Robert Gottlieb, Roger Straus. I didn’t say I liked them all. But I admired them.

In a highly competitive market, is individuality one of the casualties?

Individuality is what we’re offering. Imaginative writers, by definition, are different from each other. They’re trying find ways to express new attitudes, feelings, ways of being.

On publication, which is more gratifying – a brilliant launch, a satisfied author, encomiastic reviews, or rapid sales?

Rapid sales! – because it means people are really paying attention. And this is a business, which is one of the wonderful things about it, in fact. Non-profit publishing has no appeal for me. But many great books don’t enjoy great popularity going out the gate – or ever. And they have very real satisfactions, too.

What’s the current outlook for new writing of quality?

I think it’s pretty much what it’s always been: a crap-shoot. I do believe that great work is – eventually – recognised. But the ways this happens are many and sometimes tortuous. Think of Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard, one of the twentieth century’s greatest novels, which the author worked on for decades; it was published only after his death. The book is immortal, as is the author’s reputation. But he was not. That’s an extreme case. But writing and reception are two dissociated channels of activity. There are lots of publishers desperate to find the Trumpian Leopard. But will they recognise it when they see it?

Jonathan Galassi is president and publisher of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, which he joined in 1985. He has translated the poetry of Leopardi and Montale. His own poetry appears in three collections, most recently, Left-Handed: Poems (2012). He has published one novel, Muse (2015).

Comments powered by CComment