- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Gay Studies

- Custom Article Title: Robert Reynolds reviews 'Getting Away with Murder' by Duncan McNab

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

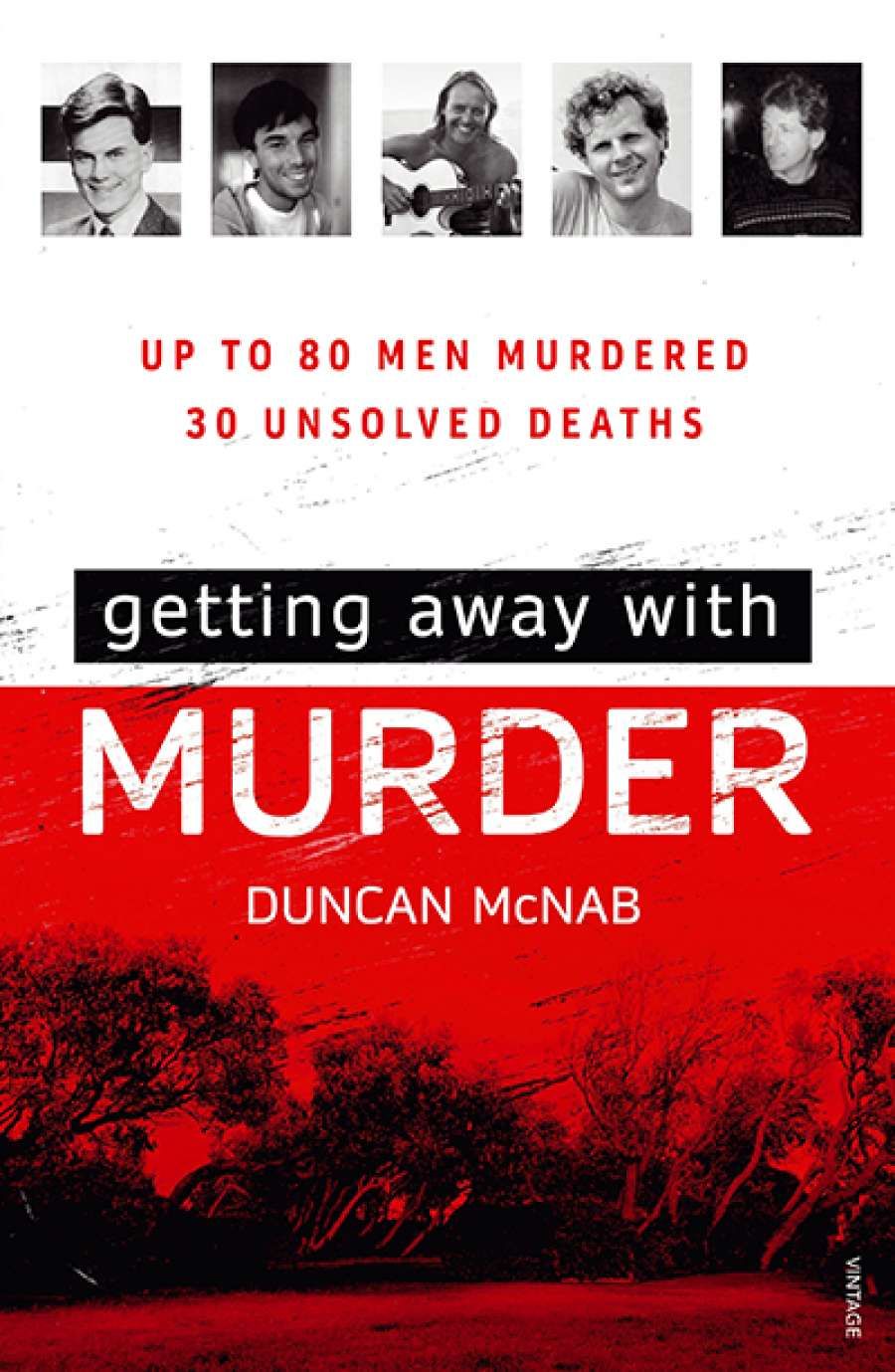

- Book 1 Title: Getting Away with Murder

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage Books $34.99 pb, 303 pp, 9780143780786

As McNab notes, the 1980s was a difficult time for the Sydney gay community. Homosexuality may have been decriminalised in NSW in 1984, but many gay men remained reluctant to report homophobic violence, not least because there was a pervasive belief that the police didn’t care. These attacks often took place in secluded public spaces where gay men cruised for sex. Fear of exposure and shame may have been another reason why bashing victims were loath to report the violence. Public hysteria about AIDS was inflamed by the tabloid press and by right-wing morals crusaders such as Fred Nile. In many ways, the 1980s was something of a perfect storm for homophobic violence in Sydney. Fifteen years of gay rights activism and the growth of a gay ghetto had turned parts of Sydney into visibly gay areas. This activism and overt gay life attracted attention, as it was meant to. But gay pride and gay neighbourhoods ran alongside patchy public acceptance of homosexuality and a deadly epidemic. Moreover, Australian masculinity remained resolutely heterosexual, and one way to prove one’s heterosexuality was to bash a poof. Paradoxically, the increased visibility and incremental social acceptance of homosexuality in the 1980s may have heightened the risk of homophobic violence. Prosaically, gay bashers had a better idea where to find their victims.

I suspect this book is primarily written for true-crime aficionados. McNab, who certainly knows how to pen a page-turner, has written previously in the genre, including a best-seller on the corrupt policeman Roger Rogerson (2016), now serving time for a drug murder. McNab plots his way through serial gay bashings and probable gay murders in Sydney during the 1980s and 1990s, including the death of Wollongong television news reader Ross Warren, whose mother, like Steve Johnson, refused to be fobbed off by a lethargic police investigation. McNab has also sought out gay men who survived these attacks. Their initial relief at survival has curdled over the years; now they bridle at the lack of serious police attention. In bracing prose, McNab talks to men who were once gay bashers: ‘To be honest, I wanted to knock them out because I hated gafs [their term for gay men] at that stage.’

Duncan McNabIn many ways, the New South Wales Police Force is the central player of this book. McNab demonstrates how the institutional homophobia of the Sydney Police Force corrupted good investigative practice. He sketches the sorry postwar treatment of gay men by the police, not least the art of ‘peanutting’: the practice of stationing handsome plain-clothed officers in public toilets with the intent to entrap same-sex-attracted men. Practised by the police until the late 1970s, this exercise had the handy effect of inflating the number of arrests, which also kept the authorities happy. At the same time, McNab is at pains to point out that there were police officers and detectives who went against the institutional grain and treated gay men respectfully and also treated violence against same-sex-attracted men seriously.

Duncan McNabIn many ways, the New South Wales Police Force is the central player of this book. McNab demonstrates how the institutional homophobia of the Sydney Police Force corrupted good investigative practice. He sketches the sorry postwar treatment of gay men by the police, not least the art of ‘peanutting’: the practice of stationing handsome plain-clothed officers in public toilets with the intent to entrap same-sex-attracted men. Practised by the police until the late 1970s, this exercise had the handy effect of inflating the number of arrests, which also kept the authorities happy. At the same time, McNab is at pains to point out that there were police officers and detectives who went against the institutional grain and treated gay men respectfully and also treated violence against same-sex-attracted men seriously.

McNab concludes his book acknowledging ‘a gang of old coppers who’ve always given a damn ... reminders of what we should expect from our police’. There is a passion for justice, then, that courses through Getting Away With Murder. McNab wants justice for those men who survived homophobic violence in the 1980s, as well as justice for the families, friends, and lovers of those men who didn’t. Perhaps, above all, he hankers for a just and accountable New South Wales Police Force.

Comments powered by CComment