- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cricket

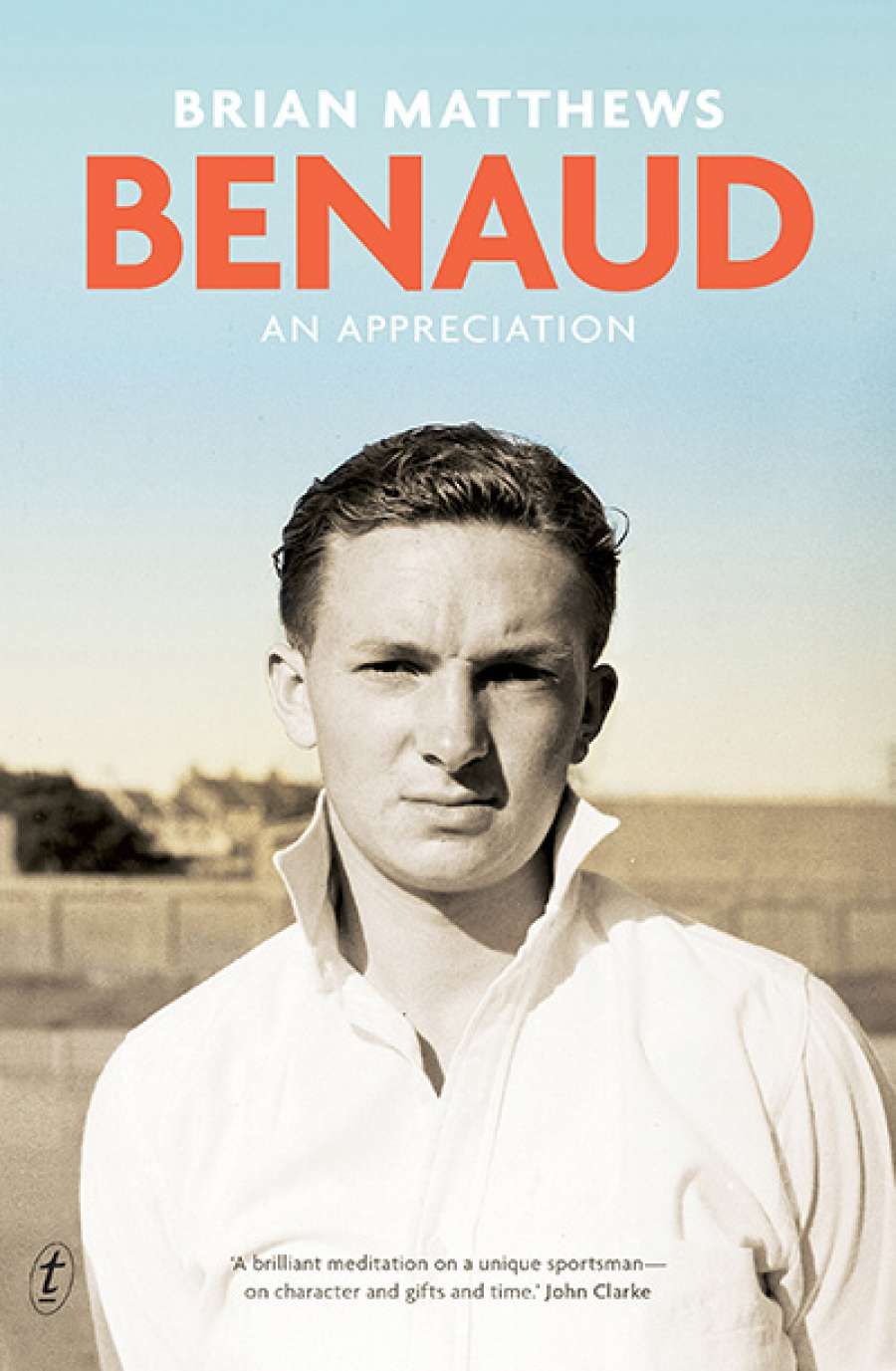

- Custom Article Title: Varun Ghosh reviews 'Benaud: An appreciation' by Brian Matthews

- Custom Highlight Text:

For more than half a century, Richie Benaud (1930–2015) graced the game of cricket around the world. A dashing batsman and fierce leg-spinner, Benaud was the first ...

- Book 1 Title: Benaud

- Book 1 Subtitle: An appreciation

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing $29.99 pb, 216 pp, 9781925355581

Enter Frank Worrell and Richie Benaud – two charismatic, attacking captains ready to do battle. Matthews expertly weaves together the historical significance and high drama of the game – Donald Bradman exhorting the Australians to play attractive cricket, Gary Sobers’s masterly century, Benaud pushing for an improbable win on the final day, the two crucial run outs that tied the game, and the teams’ famous joint celebration afterward.

The series reversed the ailing fortunes of Test cricket in Australia. According to journalist Ian Wooldridge: ‘[Benaud] orchestrated probably the most thrilling Test series ever played ... which began with the first Tied Test in history and ended with 80,000 people lining the streets of Melbourne to send a narrowly defeated West Indian team on their way home.’ When Australia retained the Ashes in England later in 1961, Benaud’s reputation as a brilliant captain was set.

Benaud once famously summarised his approach to television commentary as follows: ‘Put your brain into gear and if you can add to what’s on the screen then do it, otherwise shut up.’ This deceptively simple formulation belied a long and assiduous apprenticeship at the start of his broadcasting career at the BBC under Tom Sloan (Head of Light Entertainment) and Peter O’Sullevan (‘The Voice of Racing’). Here Benaud learned, among other things, the value of economy.

The hours were long, the pressure intense and the lessons, for future reference, were abundant, but if there was one characteristic that these eloquent talkers shared it was reticence. They never said too much, mostly they said just enough or perhaps just short of enough, leaving irony, pregnant pause or rhythm to do the rest.

Richie Benaud, 1963 (National Archives of Australia)Matthews’s description of this period of training makes for compelling reading. He also offers an insightful critique of Benaud’s writing, noting that Benaud was best when he replaced ‘no-nonsense attention to documentary truth and the rather stern insistence on the authorial voice’ with a more narrative approach.

Richie Benaud, 1963 (National Archives of Australia)Matthews’s description of this period of training makes for compelling reading. He also offers an insightful critique of Benaud’s writing, noting that Benaud was best when he replaced ‘no-nonsense attention to documentary truth and the rather stern insistence on the authorial voice’ with a more narrative approach.

Describing Benaud’s book, A Tale of Two Tests (1962), Matthews writes: ‘There is no lack of detail about the tactics, skills and fluctuations of these matches, but their sense of story and the underlying excitement of the teller of the story is in the mode of fiction and has some of the freedoms of fictional narrative.’

Interestingly, Matthews quotes Trinidadian journalist and historian C.L.R. James on the subject of cricket writing:

Writing critically about ... cricket and cricketers ... is a difficult discipline. The investigation, the analysis, even the casual historical or sociological gossip about any great cricketer should deal with actual cricket, the way he bats or bowls or fields, does all or any of these. You may wander far from where you started, but unless you have your eyes constantly on the ball, in fact never take your eyes off it, you are soon not writing about cricket, but yourself (or other people) and psychological or literary responses to the game. This can be and has been done quite brilliantly, adding a little something to literature but practically nothing to cricket, as little as the story of Jack and the Beanstalk (a great tale) adds to our knowledge of agriculture.

Unfortunately, large parts of this book meander into less fruitful territory. The book variously digresses into an account of a local council fight over Benaud’s childhood backyard, speculation on the influence of Benaud’s French Huguenot ancestry on his character, and a bizarre passage about the naming of the eponymous music group, The Benaud Trio.

Richie Benaud (photograph by Steve Terrill, Flickr)

Richie Benaud (photograph by Steve Terrill, Flickr)

Other parts of the book are almost polemical. Matthews quotes at length from Geoff Lemon’s contumelious piece in the Guardian in 2015 about the failings of the post-Benaud Australian commentary team. While many of Lemon’s points are well-taken, the extensive quotation jars. Similarly, Matthews’s critique of a book about World Series Cricket called Ten Turbulent Years (to which Benaud contributed) feels distinctly out of place. Despite these weaknesses, Benaud: An appreciation offers an intriguing, if unfinished, portrait of the man.

Comments powered by CComment