- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Military History

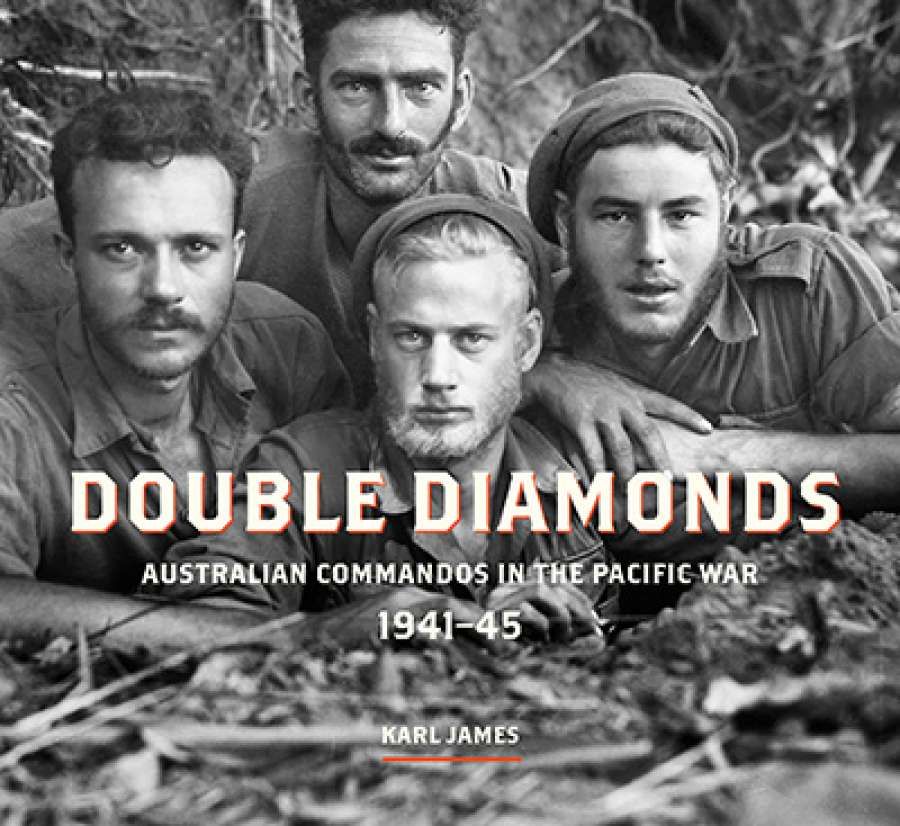

- Custom Article Title: Kevin Foster reviews 'Double Diamonds: Australian commandos in the Pacific War 1941-45' by Karl James

- Custom Highlight Text:

The recent scandal over Facebook’s censorship of Nick Ut’s 1972 photograph of ‘Napalm girl’, Kim Phuc, offers a salutary reminder of photography’s stubborn ...

- Book 1 Title: Double Diamonds

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian commandos in the Pacific War 1941-45

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb, 231 pp, 9781742234922

In the case of World War II, the majority of photographs in the Australian War Memorial were gathered not by the civilian photographers of the Department of Information, but by the uniformed photographers of the Military History Section, who, as attested servicemen, were sworn to serve the Commonwealth. Directed to record every aspect of the nation at war, from battle to battalion mundanities – postal delivery, fuel supply, sporting events – it is a miracle they produced any images of note. But they did. Their technical proficiency and artistic eye, honed on newspapers and in photographic studios before the war, have bequeathed us a trove of individual and group portraits, landscapes, action shots, and an assortment of enemy dead. Karl James employs a selection of these images, and some well-chosen war art, to illustrate his history of Australia’s commando companies in the Pacific War. Taken together, the photographs offer a candid portrait of an army at war in all its demotic glory. Belts unbuckled, hats askew, a Sam Browne belt jerry-rigged from string, the men sprawl under tarpaulins, recline in long grass or by rivers, often caught unawares by the camera. Cheerful, triumphant, tired, frightened, the images offer a powerfully human record of an army half-dead on its feet, battling the manifest hostility of the environment as much as an unseen enemy.

Private Henry ‘Harry’ Lake, 1942, a sniper who was one of the oldest men in the 2/5th Independent Company (from the book under review)If we lament the fact that these photos would never get past today’s hypersensitive PR flak, we should reflect that most of them suffered the same fate in their day, never reaching the newspapers. Clearly, photos that betray the human face of the men and women who fight our wars were no more popular in the 1940s than they are now. Directly lodged in the War Memorial, they, and thousands like them, have gathered dust for almost seventy years. It is time more of them saw the light: outstanding images in their own right, they will illuminate our record of the South West Pacific campaigns.

Private Henry ‘Harry’ Lake, 1942, a sniper who was one of the oldest men in the 2/5th Independent Company (from the book under review)If we lament the fact that these photos would never get past today’s hypersensitive PR flak, we should reflect that most of them suffered the same fate in their day, never reaching the newspapers. Clearly, photos that betray the human face of the men and women who fight our wars were no more popular in the 1940s than they are now. Directly lodged in the War Memorial, they, and thousands like them, have gathered dust for almost seventy years. It is time more of them saw the light: outstanding images in their own right, they will illuminate our record of the South West Pacific campaigns.

Sadly, James doesn’t make nearly enough of the photographs. This is illustrated history in the most traditional sense. The text, necessarily foreshortened by the abundance of images, proffers a synopsis of the commandos’ South West Pacific campaigns, their individual actions, signal triumphs, and defeats. The photos illuminate the main narrative, but they find no explicit place in it. Detailed descriptions of each image are confined to a separate, accompanying apparatus. The book cries out for a more detailed engagement with images that enrich our understanding of what these men endured, the conditions they battled, the equipment they used, the local peoples who helped them, and the enemy they hunted and killed. That they challenge the approved account of Australia’s triumph in the South West Pacific is all the more reason why they should have shaped the narrative. The photos have their own story to tell, and it is only by an act of will that the book ignores it.

Private William Whelton, 1943 (from the book under review)James, a senior historian in the War Memorial’s Military History Section, and as such the professional ancestor of the men who took these photos, perhaps felt constrained by his position in the belly of the myth-making engine, or else trapped by the rigid conventions of military history. Too timorous, or perhaps uncertain about how to break away from his dominating genre and its preoccupations, he fails to fully exploit his rich visual resource and to offer something genuinely novel to our understanding of what our troops endured. The concerns of military history are important and valuable, and they have their place – but this is not it. Let the pictures speak – they have a hell of a story to tell.

Private William Whelton, 1943 (from the book under review)James, a senior historian in the War Memorial’s Military History Section, and as such the professional ancestor of the men who took these photos, perhaps felt constrained by his position in the belly of the myth-making engine, or else trapped by the rigid conventions of military history. Too timorous, or perhaps uncertain about how to break away from his dominating genre and its preoccupations, he fails to fully exploit his rich visual resource and to offer something genuinely novel to our understanding of what our troops endured. The concerns of military history are important and valuable, and they have their place – but this is not it. Let the pictures speak – they have a hell of a story to tell.

Comments powered by CComment