- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Shannon Burns reviews 'The Life of D.H. Lawrence' by Andrew Harrison

- Book 1 Title: The Life of D.H. Lawrence

- Book 1 Biblio: Wiley-Blackwell, $134.95 hb, 272 pp, 9780470654781

Andrew Harrison does just that, portraying Lawrence as an imperfect but truthful man who possessed probing artistic integrity. He opens The Life of D. H. Lawrence by considering Lawrence’s views about the practice of literary biography. We learn that Lawrence once hoped to write a biography of Robert Burns but felt that he wasn’t ‘Scotchy enough’. Of John Lockhart’s gallingly inaccurate Life of Robert Burns (1828), Lawrence says: ‘Made me spit! Those damn middle-class Lockharts grew lilies of the valley up their arses, to hear them talk.’

Lawrence, Harrison says, felt that a biographer should share the core aspects of their subject’s experiences – relating to nationality, class, and temperament – in order ‘to understand the writing and not pay mere lip-service to its meaning’. By these standards, Harrison, who has produced a carefully researched but often-bland book, seems temperamentally unsuited to the role of Lawrence’s biographer. He is, however, well attuned to the nuances of nationality and class.

Lawrence, Harrison tells us, was born in 1885 in the grim coal mining district of Eastwood, at a time when ‘[d]ust in the air created a host of respiratory and pulmonary problems for residents; tuberculosis and bronchitis caused the largest percentage of fatalities in the district, but there were also regular epidemics of measles, diphtheria, diarrhoea, scarlet fever and whooping cough’. Harrison implies that Lawrence’s delicate sickliness as an infant was a product of the environment in which he was born, and notes that ‘problems with his lungs would haunt him throughout his life’. Lawrence died from tuberculosis in his forty-fifth year.

Lawrence’s parents were a bad match. His father, Arthur, was a miner who disliked books and felt at home in working-class society, while his mother, Lydia, revered literature and ‘was invested in a determined resistance to the outlook and values of her working-class neighbours’. Lydia was a teetotaller who ‘insisted on looking above and beyond Eastwood for her fulfillment’ and ‘fully intended to lift her children out of their present circumstances’, while Arthur knew how to enjoy himself in unglamorous company. Because Lawrence was one of Lydia’s favoured children, he felt pressured ‘to hate his father “for Mother’s sake”’.

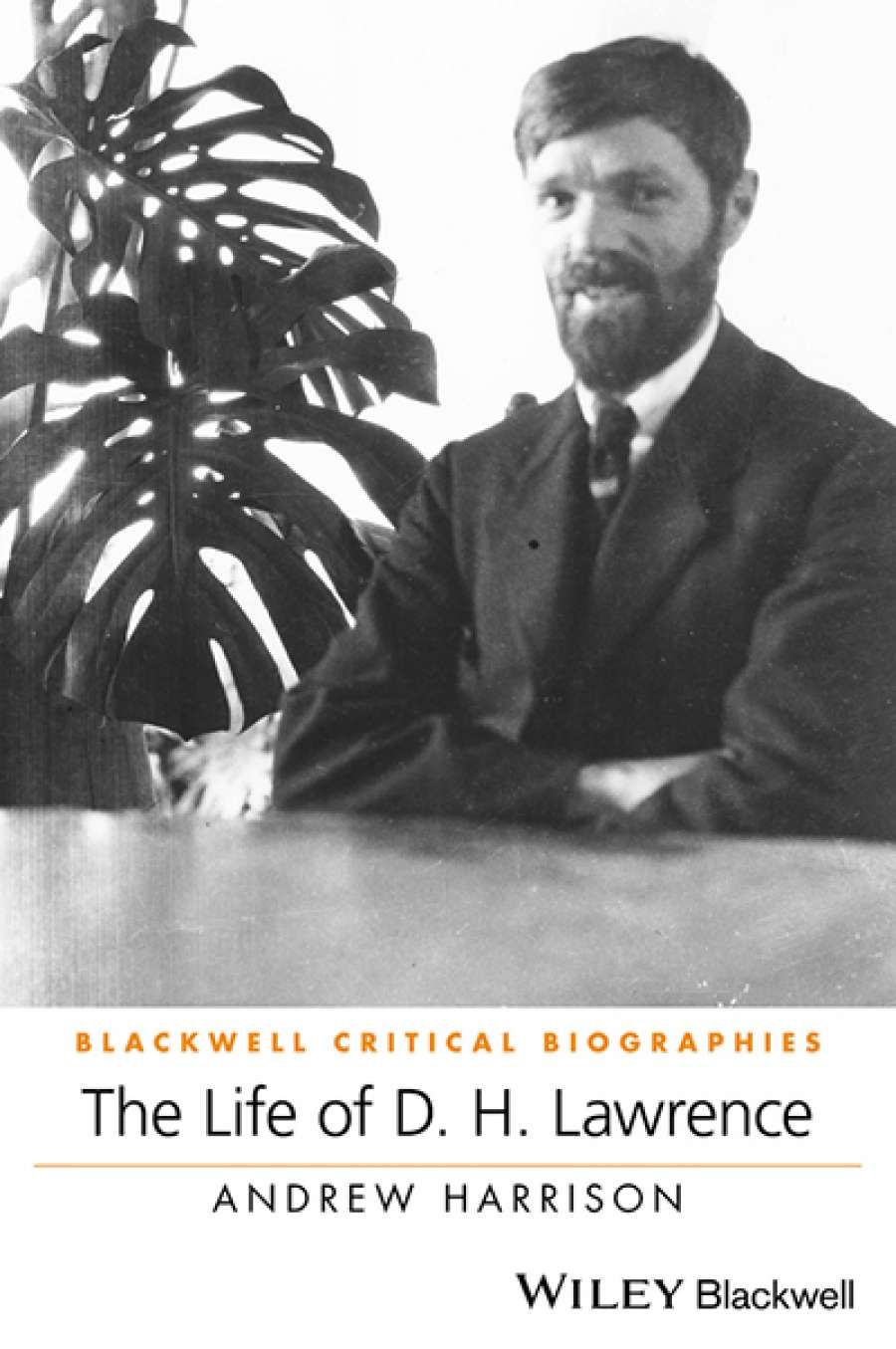

D. H. Lawrence in 1915 (photograph by Ottoline Morrell [1873–1938], National Portrait Gallery/Wikimedia Commons)Lawrence went from being a sickly infant to a sickly child who excelled academically but was ‘tormented by his peers’ because he liked to play with girls He trained and worked as a teacher in early adulthood before concentrating on writing and meeting his great love, Frieda.

D. H. Lawrence in 1915 (photograph by Ottoline Morrell [1873–1938], National Portrait Gallery/Wikimedia Commons)Lawrence went from being a sickly infant to a sickly child who excelled academically but was ‘tormented by his peers’ because he liked to play with girls He trained and worked as a teacher in early adulthood before concentrating on writing and meeting his great love, Frieda.

Harrison relies on Lawrence’s correspondence to unearth a great deal of information – negotiations with publishers, arrangements with agents, travel plans – untangling a convoluted knot of marginal material to little obvious purpose. We learn that, following a period of illness, Lawrence ‘received eggs from May Holbrook, two chickens from William Ewin (or ‘Eddie’) Clarke (Ada’s fiancé), and a letter from Agnes Holt, inviting him to visit her and her new husband in their home at Ramsey on the Isle of Man’. None of this goes anywhere. Soon after, Harrison informs us that ‘Lawrence arranged to spend a few days in London: he saw Austin Harrison, and on the afternoon of 25 April he went to the Heinemann offices to receive feedback on his poems, afterwards meeting Ben Iden Payne to discuss plans for staging one of his plays. None of the exchanges would assist his work in any significant way ...’ That last line is the kicker. Populating paragraphs with names, dates, and places in order to reveal little of obvious value is one of Harrison’s specialties.

At times, the facts of Lawrence’s life are stated in chronological order. He did this. He did that. He wrote a letter. He sent a story off. He got angry. He got sick. Frieda took a lover. He expressed approval. This flattened style can produce a curious affect, especially when a striking detail is followed by incidental information. For instance, after informing us that Lawrence and his sister helped their mother die with an overdose of medication, Harrison writes in the following sentence (same paragraph too): ‘Through the Waterfields, Lawrence and Frieda were introduced to a small coterie of other wealthy ex-pats in the area, including the Huntingdons, Pearses and Cochranes.’ From the way he presents them, it is not obvious that Harrison sees a difference in value between these two kinds of information, and his unwillingness to dwell on striking details and draw out their importance to Lawrence’s life and fiction is intriguing. While many biographers insist on extracting too much meaning from every minor event they describe, Harrison skips along largely untroubled.

View of the Pacific Ocean from ‘Wyewurk’, the house in Thirroul (NSW) where D.H. Lawrence lived and wrote his novel Kangaroo in 1922 (photograph by Peter Rose)

View of the Pacific Ocean from ‘Wyewurk’, the house in Thirroul (NSW) where D.H. Lawrence lived and wrote his novel Kangaroo in 1922 (photograph by Peter Rose)

It is partly for this reason that the presentation of the book as a ‘critical biography’ is dubious; we learn a great deal about the dates and circumstances surrounding each major and minor work, and of Lawrence’s dealings with editors and publishers, but there are only occasional grabs of sustained literary analysis. Instead, Harrison describes the shifts (in tone and scope) of the major novels as they are drafted, but in a scattered way, and waits to address contemporary critical approaches to Lawrence’s work in an afterword, where he suddenly comes alive.

Those who are keen to discover as much about Lawrence as they can will be excited by the minutiae of Harrison’s treatment, while others must rely on Lawrence’s enlivening eruptions. After all, a biography whose subject reacts against his publisher’s criticisms with: ‘Curse the blasted, jelly-boned swines, the slimy, the belly-wriggling invertebrates, the miserable sodding rotters, the flaming sods, the snivelling, dribbling, dithering palsied pulse-less lot that make up England today’, and who writes to his formerly close friend (the consumptive Katherine Mansfield) to inform her: ‘I loathe you, you revolt me stewing in your consumption’, will never be entirely dreary.

Comments powered by CComment