- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Television

- Custom Article Title: Michael Shmith reviews 'The Day the Music Died: A life lived behind the lens' by Tony Garnett

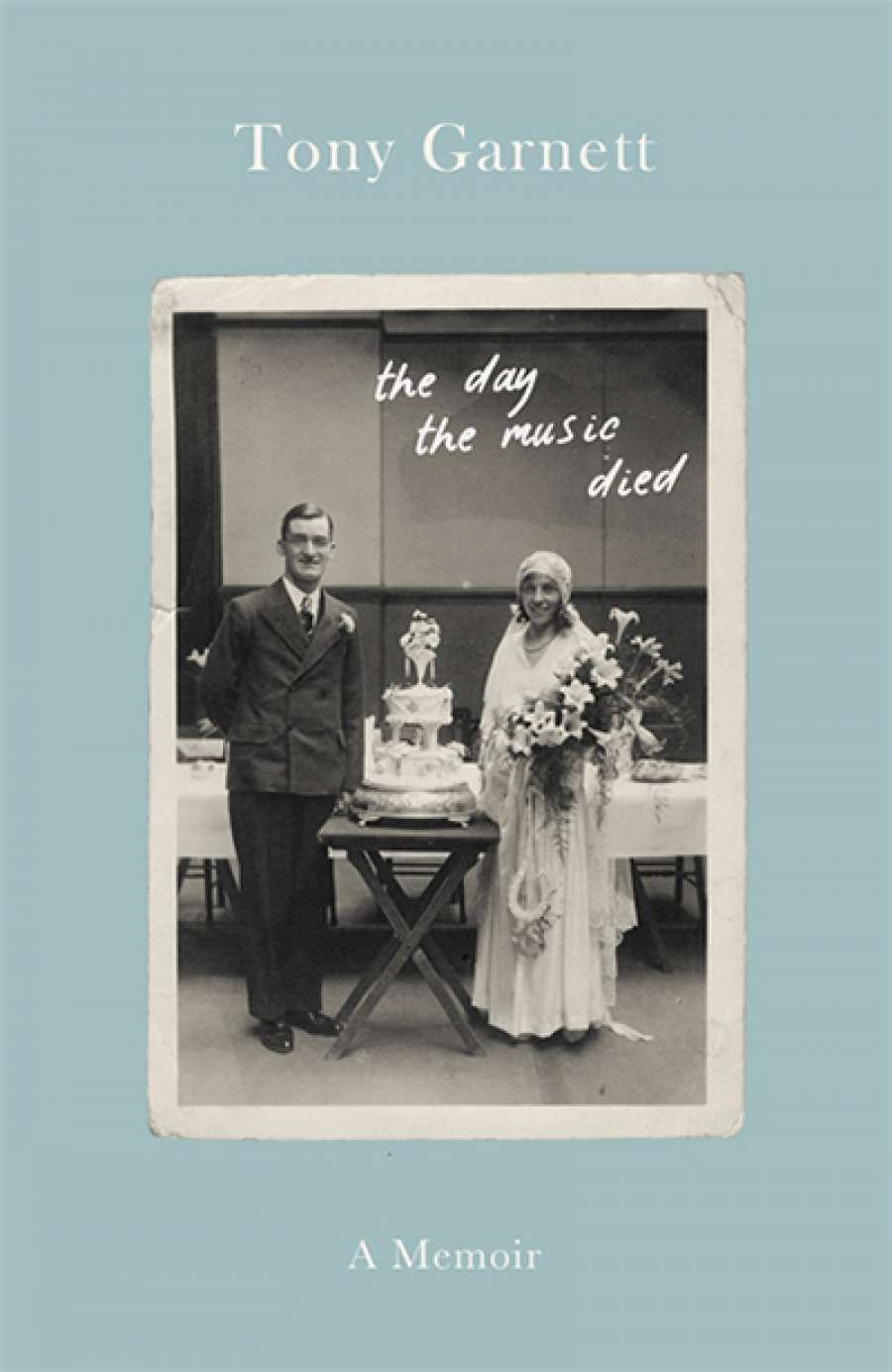

- Book 1 Title: The Day the Music Died

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life lived behind the lens

- Book 1 Biblio: Constable $49.99 hb, 306 pp, 9781472122735

In the history of television, Tony Garnett, who is now eighty, stands out as a man of perseverance, great talent, and, above all, with a streak of reticence that has successfully kept him out of the public gaze. ‘The infant refusing to tap-dance’ is how he describes his reclusiveness. ‘[F]or decades I scrupulously hid myself away, putting others up to be interviewed as the publicity machines became hungrier.’ Indeed, Garnett politely declined requests to be on Desert Island Discs and in Who’s Who. ‘I knew who I was and didn’t need to be in a book to find out,’ he said. (Yet he agreed to be interviewed, extensively and illuminatingly, for Louise Ormond’s recent documentary, Versus: The life and films of Ken Loach.)

Now he has his own book, in which he tells his story in his own time – and this is a story of heartbreak as well as achievement. In 1941, in Birmingham during the Blitz, when Garnett was five, his mother died of septicaemia contracted after a backstreet abortion; nineteen days later, his father committed suicide. These terrible events and their aftermath formed the pivotal point of Garnett’s life. Even today, as he writes, the direct memories remain vivid: ‘They play in my head, sharply focused, the voices clear, like a film.’

The Day the Music Died is indeed film-like in its narrative structure, economy of words, and setting of scenes and sequences. It is studded with affectionate reminiscence, remorseful recollections and poignant reminders. In the latter category is his discovery, in his aunt’s underwear drawer, of his father’s suicide note, which begins, ‘It is now 3 long weeks since my sweetheart was taken from me and I feel I cannot carry on without her ...’

The book moves swiftly, tellingly, from tragic childhood and life with a big and devoted family, through a sad marriage and early acting career, to the BBC and independent-film years, and voluntary exile in Los Angeles during the Thatcher years. Garnett returned to Britain in the early 1990s to run his own independent company, and the book winds up at the end of that decade. I’m sure, though, he has more to say.

David Bradley and Tony Garnett during the filming of Kes, 1969 (Film Forever/Wikimedia Commons)

David Bradley and Tony Garnett during the filming of Kes, 1969 (Film Forever/Wikimedia Commons)

The book is not without its eccentricities and comic moments. Garnett’s gimlet eye is enviable, and there are many acute observations, mostly on the kind side. Possibly not is his account of a drinking bout between two veterans of the bottle, writer David Mercer and psychiatrist R.D. Laing:

As David demolished a bottle of spirits his speech became blurred and soon degenerated into pompous nonsense. But Ronnie’s eloquent, insightful sentences kept rolling out, seemingly unaffected, indeed lubricated, by the booze; each had a subject, verb and predicate, carrying many complicated subsidiary clauses, and I would wait for it to crash. But every time he would land it smoothly and perfectly on a full stop, the meaning intact and the style elegant to the end. The alcohol’s only effect was a slower delivery.

The temptation with The Day the Music Died is to believe it should have been written, say, half a century earlier, when the influence of many of Tony Garnett’s television productions were profound and lasting. But it is precisely the long after-effects of Garnett’s pion-eering work that makes the book so relevant, so important. He managed, quietly and successfully, to combat misguided right-wing opinion (chief offender, the odious self-appointed moral censor Mary Whitehouse) and consistent opposition from high within the BBC. In doing so, Garnett set the BBC on a new course that still influences creativity and public thought. It is the story that just had to be told.

Comments powered by CComment