- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Psychiatry

- Custom Article Title: James Dunk reviews 'Finding Sanity: John Cade, lithium and the taming of bipolar disorder' by Greg De Moore and Ann Westmore

- Custom Highlight Text:

Edward sits on Sydney Harbour Bridge, considering jumping. It is 1948, and he has written several times to George VI about building a new naval base in the waters below, and not ...

- Book 1 Title: Finding Sanity

- Book 1 Subtitle: John Cade, lithium and the taming of bipolar

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin $32.99 pb, 335 pp, 9781760113704

There is some irony here. The use of lithium is in some respects a swing back to much older understandings of body and mind which saw the two as inextricable. Treatments sought to rebalance this system – a system not well understood. Early sections of the book describe the galling conditions in the asylums where Cade and his father worked. These were produced by a swing to psychological thinking from the late eighteenth century, driven by the idea that mental sufferers would respond better to gentle instruction, ordered environs, and occupational therapy than to any quantity of purgatives and emetics. This emphasis was sublimated by Sigmund Freud in the early twentieth century. Certain of his followers held that even severe psychotic symptoms could be traced back to psychological trauma, and treated by variations of the ‘talking cure’.

Australian psychiatrists were smitten with Freud; John Cade was not. Cases he treated while interned at Changi, a place made vivid in Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North (2013), convinced Cade that many people with manic depressive or schizophrenic symptoms were ‘sick people in the medical sense’. He scribbled imprecations in the margins of Freud’s books. ‘Not true. Simply not true’ appeared next to a particularly egregious claim. When, as a rising psychiatric star, Cade was asked to give the prestigious Beattie Smith lectures at the University of Melbourne, he declared, against his wife’s advice, that Freud had ‘cast a blight upon the minds of men’ that would last another half century. The psychiatrists present looked at the ceiling, groaned, and smirked; one put it down to Cade’s Catholicism.

This is strong, thorough biographical writing, woven from multiple perspectives, humorous and fascinating. Following biographical convention, the authors map Cade from his mother and distant psychiatrist father through his youth, dwelling with him in Changi, and, after his return, highlight his discovery of lithium, and rise to professional prominence, before his death from cancer in 1980. Conventional inclusions – family holidays and personal idiosyncrasies – work to produce the image of a man. Some details are revealing: Cade enjoyed pig shooting and wrote his children bawdy limericks while touring the hospitals of Europe.

Biography is pressed into the service of medical discovery, but hovering at the margins is the suspicion that the discovery was in fact a fluke. Cade’s methodology was rudimentary. Early in his research career he spent a good deal of time injecting the urine of manic patients into guinea pigs, and then burying them. When he finally made the dramatic observation that the rodents were calmed by lithium, De Moore and Westmore find that they were probably suffering from lithium toxicity. They also note that Cade, who tried lithium himself before giving it to human patients, also experimented with calcium, magnesium, titanium, rubidium, beryllium, cobalt, nickel, zinc, tungsten, molybdenum, and selenium. Strontium made him particularly sick. Cade joked that he had eaten his way through half the periodic table. Only lithium worked.

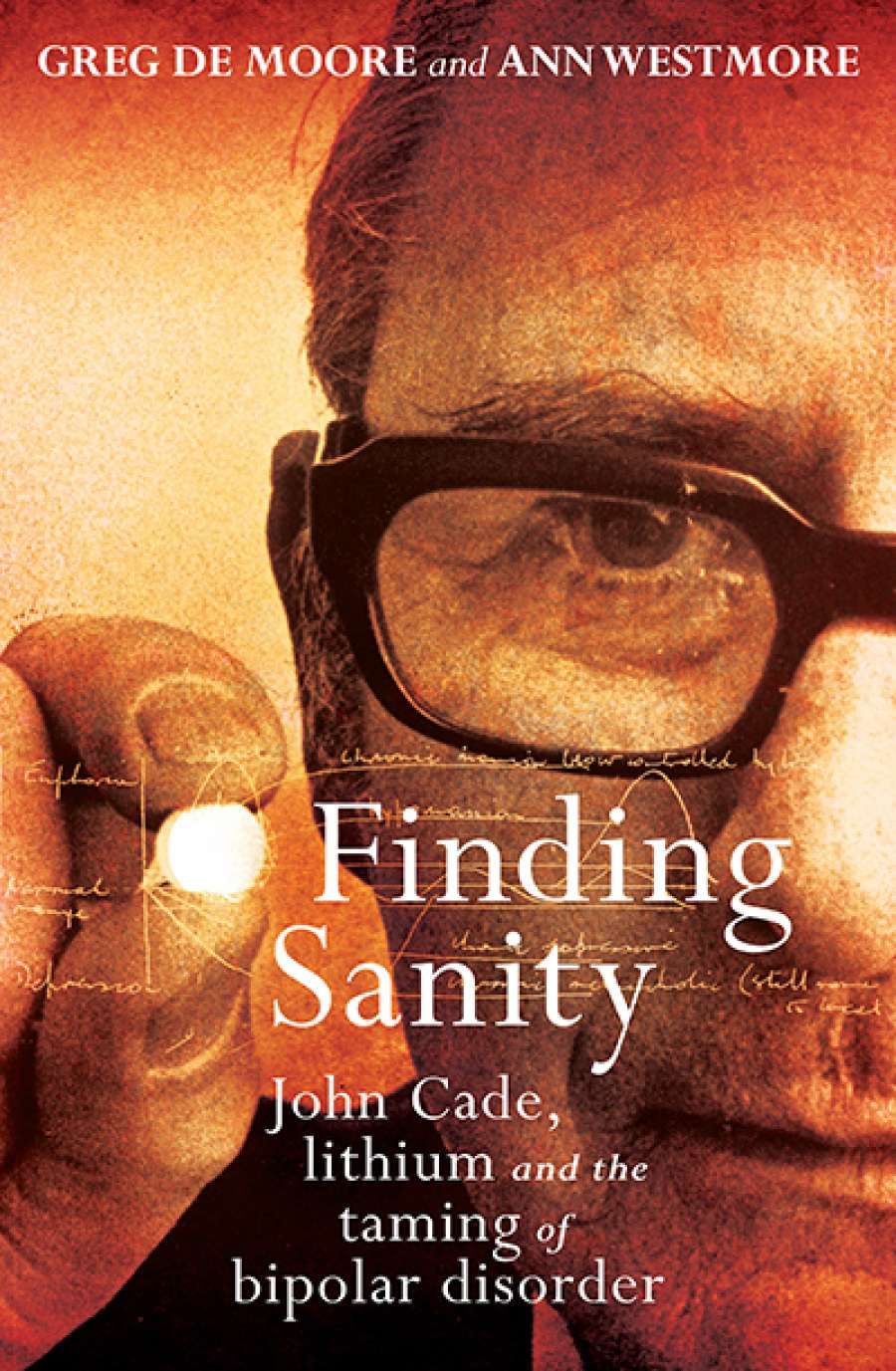

John Cade, 1974 (photograph by Terry Rowe)

John Cade, 1974 (photograph by Terry Rowe)

Was Cade a brilliant medical thinker or simply a determined, and brave, experimentalist? Jean Cade told his biographers that her husband was ‘not even a researcher’s bootlace’, and while they suggest that she may have been repeating a throwaway comment of his, they write elsewhere that well after his 1949 discovery Cade still ‘regarded himself as very much a novice’ in medical research.

If Cade was, indeed, an indifferent researcher, he still discovered lithium. While the authors leave space for readers to evaluate the costs of his experiments themselves (several patients, including Brand, died of lithium toxicity in trials), the book celebrates ‘the taming of bipolar disorder’. Its work on the human brain is still not fully understood, but it has elevated countless lives out of the depths described in Brand’s story and implied in the grim corridors and vexing straitjackets of the old asylums. The many sufferers who wrote touching letters to Cade in his retirement and to his family after his death recognise a salvific intervention. This book, then, is a nuanced celebration of intuitive experimentation and medical boldness. Timid research, John Cade would tell his students, does not lead to great discoveries.

Comments powered by CComment