- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

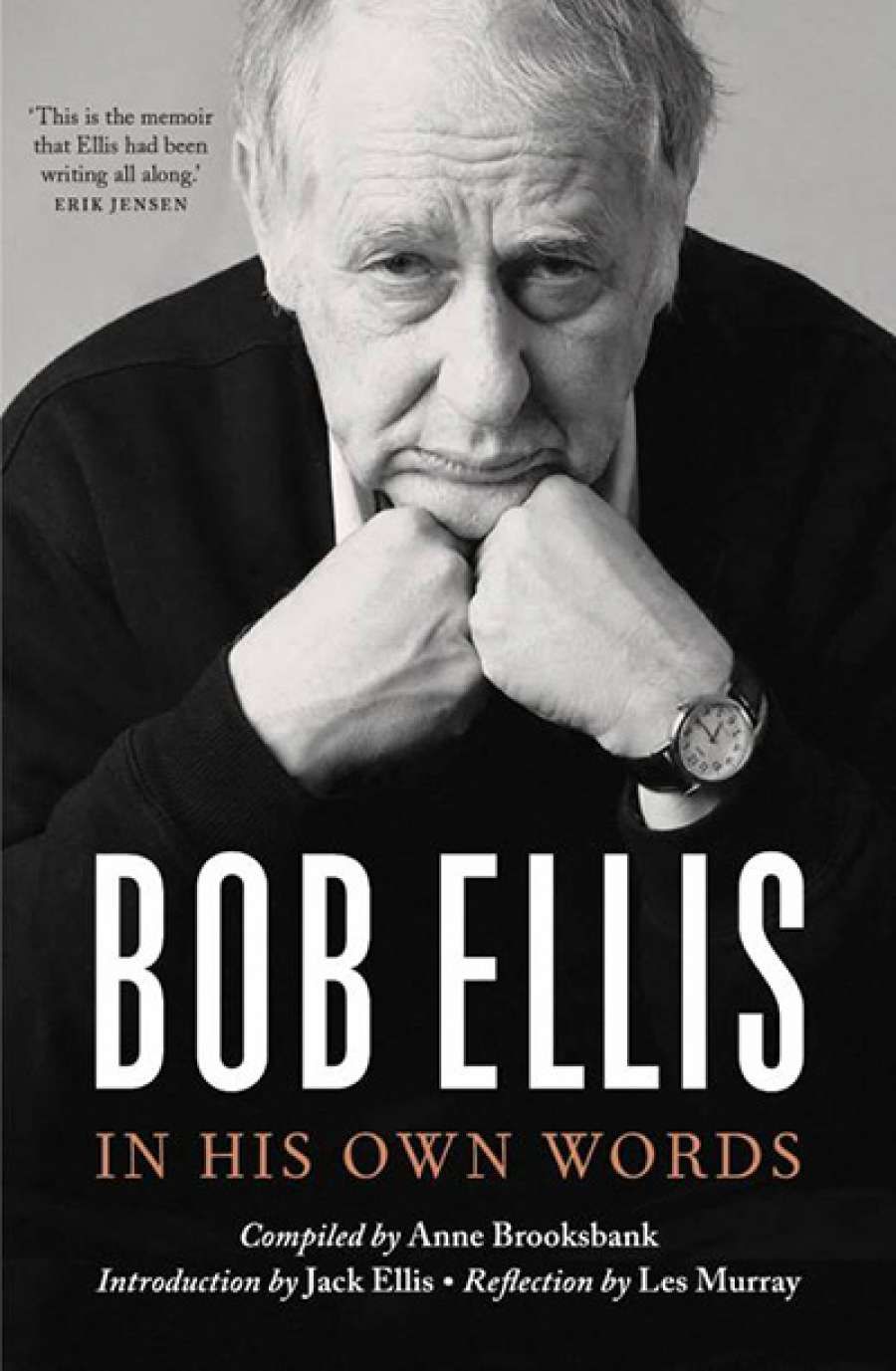

- Custom Article Title: Jan McGuinness reviews 'Bob Ellis: In his own words' by Bob Ellis, compiled by Anne Brooksbank

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his introduction to Bob Ellis: In his own words, Bob’s son Jack says of his father that ‘writing was his reason for being ... and through his writing he saw himself in conversation ...

- Book 1 Title: Bob Ellis

- Book 1 Subtitle: In his own words

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc. $34.99 pb, 376 pp, 9781863958912

In a cover line, Guy Rundle claims that ‘Bob Ellis is not merely the finest prose writer Australia has produced, he is probably the finest three or four of them.’ This reads like something Ellis might have written in one of his more florid moments, but the vintage pot-pourri is well chosen and goes a long way to vindicating Rundle’s claim. Ellis emerges as a superb and vivid wordsmith whose love of language is palpable. He writes admiringly of Barry Humphries’ ability to skewer the moment with an exact and nuanced choice of words. It is a skill he shares laced with his own brand of wit, insight, and, yes, morality, because Ellis cares deeply about the things that matter.

However, Ellis’s reputation as a shambolic, malicious, boastful, womanising, drunken bully overshadows his prodigious contribution to our culture. We have him to thank for scripting breakthrough iconic Australian films including Newsfront, Fatty Finn, Man of Flowers, My First Wife, Goodbye Paradise, and the autobiographical The Nostradamus Kid. It was he who coined the term ‘true believers’, a fitting description for Labor Party tragics like himself and the title of a television mini-series he co-wrote about the Party’s history.

It is an overshadowing to which Ellis actively contributed. Retentive baby boomers will recall public fallings-out – dating back to the 1970s, most notably with David Williamson and conducted as the riveting airing of much dirty linen in the pages of Nation Review.

Unlikely as it seems now, Bronwyn Bishop was once regarded as a future prime minister. When she moved into Ellis’s electorate of McKellar, and in the absence of a Labor Party candidate at the 1993 federal election, Ellis ran against her to everyone’s vast amusement but Bishop’s.

1998 was enlivened by the pulping of Ellis’s political memoirs Goodbye Jerusalem following a defamation case mounted by Tony Abbott, Peter Costello, and their wives. It cost Ellis’s publisher Random House $277,500 and Ellis a sideswipe from the Federal Court’s Justice Miles, who observed that the person whose reputation had suffered most was the author’s.

This very public humiliation was eclipsed a year later when married scriptwriter Alexandra Long confirmed Ellis as the father of her baby. A media frenzy ensued as Ellis refused to do a DNA test and various accounts unfurled, among them Ellis’s revelation to radio 2BL breakfast listeners of his oral sex defence. It was written for him by his wife. After tests, Ellis conceded fatherhood.

Henceforth, Ellis remained outspoken but less ubiquitous. The damage was done. In a more forgiving and less constrained society there had been a place for such ratbaggery. During an era now lamentably past, there was scope for satire in experimental theatre, our burgeoning film industry, ABC television, and publications like Nation Review and the National Times. It is in this context that Ellis should be assessed. As revealed in this posthumous book, he is also in every way a product of his background.

The child of an ardent Seventh Day Adventist mother and ALP-loving father, Ellis was raised on the New South Wales north coast. Like many children enthused by their parent’s passions, he found the ALP and the entire political scene bewitching. In adulthood he became Labor’s highly partisan, self-appointed historian, though never a member; the church not so much. It was replaced at Sydney University by what Jack Ellis describes as his father’s true religion – love of theatre, films, and their transformation of ideas into magic. But the Adventist’s sense of doom and theatrical hyperbole informed his adult conspiracy theories, dire predictions of political calamity, and loopier moments. In a poetic tribute to Ellis, Les Murray has Ellis fleeing Sydney to escape nuclear annihilation during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. Similarly, his foolhardy fight against Bronwyn Bishop was less Don Quixotesque and more as the saviour of McKellar and the nation, at least to his own mind.

Bob Ellis and Anne Brooksbank in 1976 (photograph by Robert McFarlane/National Library of Australia)

Bob Ellis and Anne Brooksbank in 1976 (photograph by Robert McFarlane/National Library of Australia)

Ellis never lost his sense of small-town country kindness and community lovingly evoked in his musings on childhood, nor the mass of insecurities they exposed him to on reaching the sophisticated cosmos. He found a compromise in the cocky-chewed house he shared with his wife and three children at Palm Beach indulging his love of the local fauna. Ellis’s descriptions of his habitat bring the place to life, as do his travels to the Wider World.

Given the contents of this book, Ellis’s legacy should be that of a distinctive and entertaining diarist–commentator on culture and politics. It is recommended on that basis, together with Ellis’s many collected writings, notably his profile of Joh Bjelke Petersen in So It Goes (1999), an immersive account of being beguiled by the old showman and a demonstration of how it takes one to fall for one.

Comments powered by CComment