- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Custom Article Title: David McCooey reviews 'The Hatred of Poetry' by Ben Lerner

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Do people hate poetry, as the title of Ben Lerner's terrific book-sized essay implies? In Lerner's account, poetry is associated with hatred and contempt, even by ...

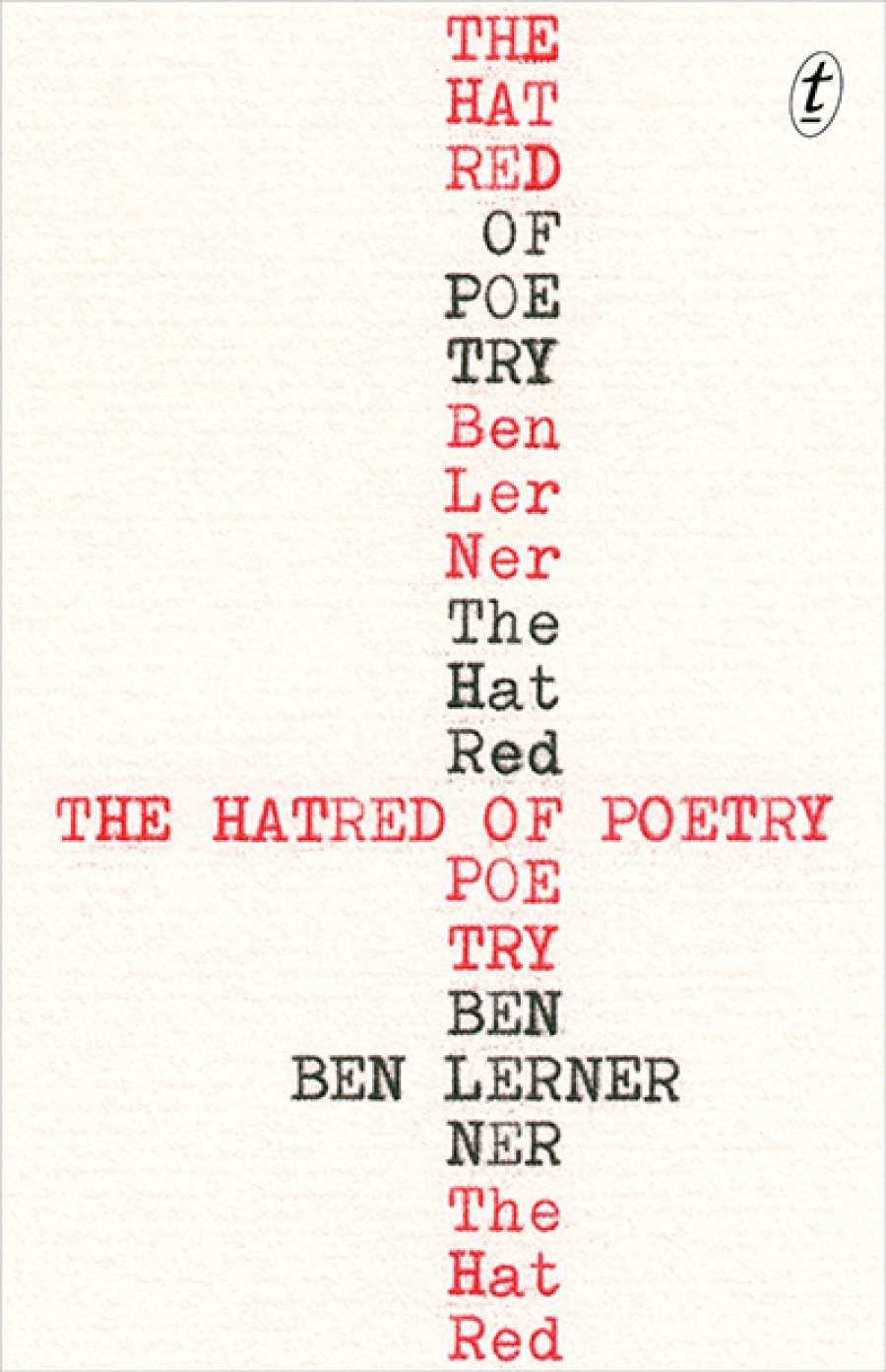

- Book 1 Title: The Hatred of Poetry

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing $19.99 pb, 86 pp, 9781925355673

Reviewers struggle with the tension between the real and the ideal, too. The review I dreamed worthy of The Hatred of Poetry and this actual review are two different things, leading me to wonder why the gap between the real and ideal figures so definitively for poetry rather than other art forms. An 'exceptionalist' argument about poetry is never explicitly made by Lerner, but it is implied throughout. And that's fine. This is a book about poetry, after all. If there is something exceptional about poetry, it is perhaps because it is a kind of Ur-art form, a kind of echo – both transcendent and disturbing – of something ancient within modernity.

Lerner is himself sensitive to the limitations of treating poetry in the abstract as 'Poetry', engaging in some powerful readings of 'actual poems' to counter the idealism he sees as central to poetry. And while he is strangely indifferent to the supposed cliquishness and internecine cultural politics of real poetry 'scenes' (surely key reasons for the hatred of poetry by non-combatants), Lerner is attentive to poetry's political status more generally. His understanding of avant-gardist approaches to poetry as actually analogous to traditionalist complaints about modern poetry, especially in terms of poetry's lack of political efficacy, is excellent polemic:

The avant garde imagines itself as hailing from the future it wants to bring about, but many people express disappointment in poetry for failing to live up to the political power it supposedly possessed in the past. This disappointment in the political feebleness of poetry in the present unites the futurist and the nostalgist and is a staple of mainstream denunciations of poetry.

As this suggests, Lerner – a poet himself – is powerfully epigrammatic: 'Poetry makes you famous without an audience'; 'Plato is a poet who stays closest to Poetry because he refuses all actual poems'. The emphasis on paradox is matched by an emphasis on negativity, something Lerner (along with many others before him) finds central to lyric poetry. This means he can read the 'famously bad' Scottish poet William McGonagall alongside Keats and Dickinson because 'The horrible and the great (and the silent) have more in common than the mediocre, or OK, or even pretty good, because they rage against the merely actual.'

This repeated emphasis on the tension between the real and the actual leads to a classically Romantic project: to 'reconcile the finite and the infinite, the individual and the communal, [so as to] make a new world out of the linguistic materials of this one'. It is not surprising, then, that Lerner attends for the most part to the great American post-Romantics, Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, and to the contemporary American poet, Claudia Rankine, whose 'American Lyrics', in their emphasis on individual experience and social change, are emphatically post-Romantic in temperament. It should also be no surprise that Lerner ends his essay in 'full-blown' post-Romantic mode, with a lyrical, autobiographical account of childhood, that acts as a digressive poetic coda, showing in prose what good poetry is supposed to do: re-present the banality of everyday life in powerfully original ways; confuse the categories of work and leisure; and engage in childlike play to produce a new adult world.

Ben Lerner (Wikimedia Commons)Interestingly, the lyrical experiences that these closing pages enumerate do not involve poetry per se, but come from the corrupted world of merchandise (the opening of a Hypermart), popular culture (watching Planet of the Apes repeatedly at a school camp), and 'high culture' ('an aggressively mediocre opera'). All of these things stand for, or rather mysteriously engender, an impulse Lerner describes as 'Poetry'. Poetry remains exceptionalist, then, because it is in fact utterly representative. The paradoxes remain.

Ben Lerner (Wikimedia Commons)Interestingly, the lyrical experiences that these closing pages enumerate do not involve poetry per se, but come from the corrupted world of merchandise (the opening of a Hypermart), popular culture (watching Planet of the Apes repeatedly at a school camp), and 'high culture' ('an aggressively mediocre opera'). All of these things stand for, or rather mysteriously engender, an impulse Lerner describes as 'Poetry'. Poetry remains exceptionalist, then, because it is in fact utterly representative. The paradoxes remain.

These paradoxes are really creative tensions. The contempt for the 'merely actual' can just as easily be applied to the idealisation of poetry. And one can love the 'merely actual' in a way one cannot love the ideal, even if that ideal cannot be wholly abandoned. These tensions, as particularly poetic tensions, can be found beyond the pages of The Hatred of Poetry. They are, for instance, thematised and satirised in the novels of the great Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño, and in the 'Roānkin' stories by Maria Takolander. Lerner's first novel, Leaving the Atocha Station (which prefigures some of the ideas rehearsed in The Hatred of Poetry) surely owes a debt to Bolaño's brilliant allegories of poetry in modernity.

Drawing attention to Lerner's account of poetry as post-Romantic is not in itself 'critique', and certainly not a dismissal, however easy that might be according to some styles of reading. The struggle between the actual and ideal is a struggle that any writer, regardless of aesthetic 'position', would understand. What I love about this book is its intelligence, its wit, and its implicit valuing of the real, however much the ideal might be valorised. To end on a prosaic footnote, though, I should say that I am married to Maria Takolander. You can't get much more cliquish than that. Don't you just hate poets?

Comments powered by CComment